2.1 Writing Purposes & Rhetorical Situation

Before drafting any piece of writing, from personal essays to research papers, you should explore what you want your readers to feel, think, say, or do about your topic. Your writing should help your readers understand a concept, adopt a particular belief or point of view, or carry out a task.

General Writing Purposes

The following are four general writing purposes, two or more of which are usually combined for greater effect:

To Inform – Presenting information is one of the most common writing purposes. In academic writing situations, students often write papers to demonstrate their mastery of the material. Journalistic writing is the most common form of informative writing, but informing readers can have its place in every writing situation. For example, in narrating her experience of a childhood vacation, a writer may also work toward informing her readers about the beauty of a particular place.

To Persuade – Persuasion is another common writing purpose. We have strong opinions on many issues, and sometimes our writing seeks to defend those views and/or convince the reader of the superiority of our position. Persuasion can take many forms, from writing to elected officials about the need for a new traffic light to an academic essay that defends the need for the death penalty in the U.S., but its aim is always to persuade. Personal essays also sometimes work toward persuasion; writers often illustrate their points through the use of narrative structures or examples.

To Express Yourself – Self-expression, or self-exploration, can be the sole purpose of some writing situations, but it can also work to further establish the writer’s presence in a piece or to illustrate a larger point. For example, a student writing about his experience with drug addiction may use that experience to make a larger point about the need for more drug treatment options.

To Entertain – Some writing merely entertains, while some writing couples entertainment with a more serious purpose. Sometimes a lighthearted approach can help your reader absorb dull or difficult material, while other times humor provides an opportunity to point out the shortcomings of people, ideas, or institutions by poking fun at them.

Specific Writing Purposes

Besides having one or more general purposes, each piece of writing has its own specific purpose—exactly what you want readers to come away with. For example, consider the differences between a paper that outlines how to change your car’s oil and one that discusses the reasons why you should change your oil. Each has its own specific purpose even though the topics are similar. Having a specific purpose in mind helps you define your audience and select the appropriate details, language, and approach that best suits them. It also helps keep you from getting off track.

In defining your specific purpose, it’s helpful to think in terms of verbs. Is your purpose to communicate or to convince? Table 2.1 shows a few examples:

| COMMUNICATING VERBS | CONVINCING VERBS |

| Define | Assess |

| Describe | Evaluate |

| Explain | Forecast |

| Illustrate | Propose |

| Outline | Recommend |

| Summarize | Request |

Understanding the Rhetorical Situation

It is common knowledge in the workplace that no one really wants to read what you write, and even if they want to or have to read it, they will likely not read all of it. So how do you get your reader to understand what you need quickly and efficiently? Start by doing a detailed Needs Assessment—make sure you understand the “rhetorical situation.” Before you begin drafting a document, determine the needs of your rhetorical situation.

The “rhetorical situation” is a term used to describe the components of any situation in which you may want to communicate, whether in written or oral form. To define a “rhetorical situation,” ask yourself this question: “Who is talking to whom about what, how, and why?” *See Chapter One: What is…? or view the PALES slideshow on Prezi.

WRITER refers to you, the writer/creator/designer of the communication. It is important to examine your own motivation for writing and any biases, past experiences, and knowledge you bring to the writing situation. These elements will influence how you craft the message, whether positively or negatively. This examination should also include your role within the organization, as well as your position relative to your target audience.

AUDIENCE refers to your readers/listeners/viewers/users. Audience analysis is possibly the most critical part of understanding the rhetorical situation (see. Consider Figure 1.3.2 below. Is your audience internal (within your company) or external (such as clients, suppliers, customers, other stakeholders)? Are they lateral to you (at the same position or level), upstream from you (management), or downstream from you (employees, subordinates)? Who is the primary audience? Who are the secondary audiences? These questions, and others, help you to create an understanding of your audience that will help you craft a message that is designed to effectively communicate specifically to them.

MESSAGE refers to what information you want to communicate. This is the content of your document. It should be aligned to your purpose and targeted to your audience. While it is important to carefully choose what content your audience needs, it is equally critical to cut out content that your audience does not need or want. It is important to avoid wasting your audience’s time with unnecessary or irrelevant information. Your message should be professional, and expressed in a tone appropriate for the audience, purpose, and context.

CONTEXT refers to the situation that creates the need for the writing. In other words, what has happened or needs to happen that creates the need for communication? The context is influenced by timing, location, current events, and culture, which can be organizational or social. Ignoring the context for your communication could result in awkward situations, or possibly offensive ones. It will almost certainly impact your ability to clearly convey your message to your audience.

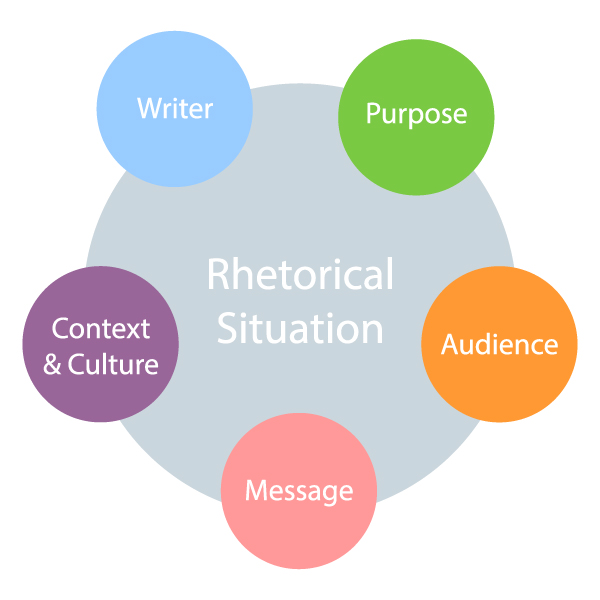

Figure 2.1 is a visual representation of the rhetorical situation:

How Writers and Readers Interact

Writers and readers interact in unique ways. In all cases, writing is a one-way flow of information. Therefore, writers must consider and include all of their readers’ needs. Every reader is different, but an effective writer must anticipate what will be most useful to the audience. Additionally, the world is extremely diverse. Some readers may be more relaxed or open-minded than others. For this reason, writers must learn to be conscientious in their writing to ensure they won’t discourage or offend any of their readers. If a reader is offended, any decision made will likely not be made in the writer’s favor. Effective writing eliminates unnecessary pieces of information and ensures a concise document.

When writing a document you must start with who your audience is and what they need to know. It’s also important to take any cultural differences into consideration.

Additional Resources

- “The Rhetorical Situation,” a video from Joy Robinson, UAH Technical Writing

- “Rhetorical Situations” (article from the Purdue OWL)

CHAPTER ATTRIBUTION INFORMATION"Understanding the Rhetorical Situation." Technical Writing Essentials. [License: CC BY-SA] "Rhetorical Nature of Technical and Professional Writing." Lumen Technical Writing. [License: CC BY-SA] |