12.2 Experience, Expression, and Equity

Elizabeth B. Pearce, Christopher Byers, and Carla Medel

“If you have only two pennies, spend the first on bread and the other on hyacinths for your soul.”

– Arab Proverb

In this chapter, we will study the effects of visual culture on how families function in the United States.

Figure 12.1. This community mural of two boys in nature can be found in Comuna 13, a neighborhood in Medellín, Columbia.

You may wonder about the inclusion of art and beauty in a text that discusses the needs of families. But it can be argued that American individuals and families need art both as individuals and as a civilization. In addition, how society defines art and what is considered to be “beautiful” is relevant to equity and family outcomes.

Visual culture is described as the combination of visual events in which “information, meaning, or pleasure” are communicated to the consumer (Mirzoeff, 1998). The information that we take in through our eyes is both immense and psychologically powerful, affecting us in ways that take time and cognition to understand (Figure 12.1). It is the intent of this chapter to highlight the ways in which visual culture affects families, both in the way we view ourselves, and in the ways we can access resources such as education, employment, and wealth.

Art is one way people share ideas, express themselves, and communicate. Consider the print of Claude Monet’s The Water Lily Pond hanging in your doctor’s office (Figure 12.2). What about the graffiti you passed on the way to the bus stop? Artistic expression exemplifies the richness of a culture and energizes our thought processes. We are exposed to art, design, and creativity all day long, whether we realize it or not.

Figure 12.2. The Water Lily Pond [oil on canvas], ca. 1917-19 by Claude Monet hangs in the Albertina, a museum in Vienna, Austria, but reproductions of Monet’s art can be found everywhere.

Art is one way in which people share ideas, express themselves, and communicate. How and where an individual is able to access art is largely related to the values and beliefs a culture holds as a standard for determining what is desirable in a society, both by artistic and by beauty standards.

Individuals have specific, individualized beliefs, but can still share collective values. Values shape how a society views what is considered beautiful and what kinds of art are valued. Beauty is a concept that is flexible and that changes depending on where and when you are living. A family’s access to art that speaks to their culture, interests, and imagination depends on what is available in the popular media and accessible in their geographic region. In Western culture, art was historically housed in museums. In Indigenous cultures, art often takes the form of useful objects, such as baskets, an example shown in Figure 12.3, and clothing.

Figure 12. 3. In the Western Apache culture, women traditionally produced storage baskets for family use. Thisbasket, likely made in Arizona circa 1890, is now housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Today art and other imagery are easily accessible in digitized forms of technology, which are accessed through the internet. These readily available ways that people can use and access visual culture can breed unrealistic expectations for many people.

For example, with the rise of “selfies,” social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat can provide individuals outlets to shape and shift self images so that they can conform more easily to the dominant social standard of beauty.

It can be posited then that the dominant culture’s expectation of physical beauty can and has been what has most heavily influenced Western culture. The media and films portray a particular standard of beauty, setting up a tension between conforming to this standard, individualistic preferences, and cultural practices that may conflict with the idealized concept of beauty.

Beauty perceptions affect family members of all ages; the multidirectional relationship of families and society affects the parents and guardians of children, which in turn affects the kids, and the grandkids, and so on. The patterns are shown in the way we rear our children, which is the emotional connection within the private family.

12.2.1 Art: A Historical Context

Expression is a fundamental need for human beings. Some human developmental theories, like Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, demonstrate that once humans have their basic needs met, such as food, water, shelter, love, nurturance, and housing, they can begin to move into more creative avenues of self-expression and self-actualization.

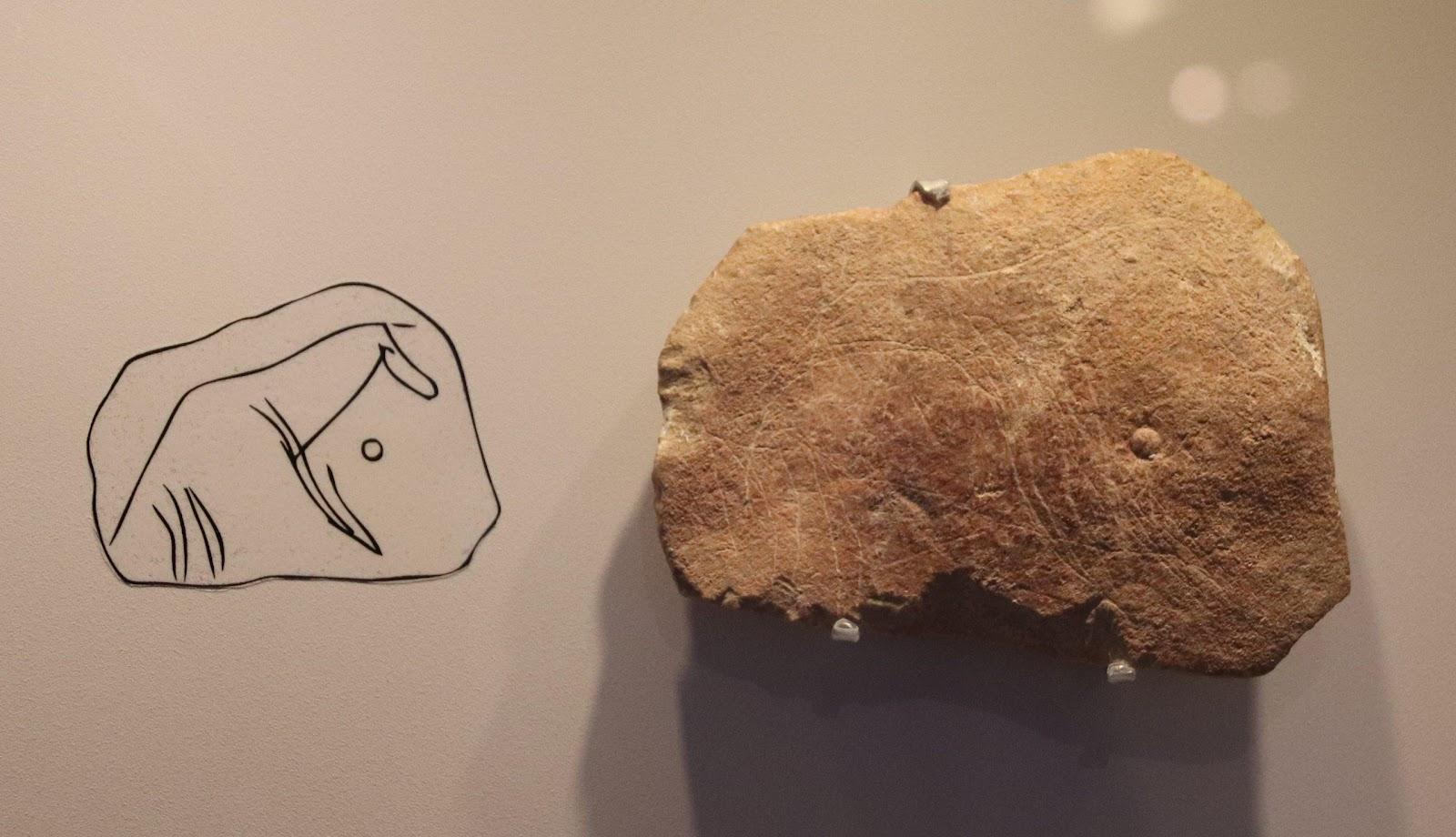

Throughout history, humans have produced artworks. One would be surprised at how far back in time humans were attempting to engage in expression. Scientists have recently found shells dating back 500,000 years ago that were engraved with small geometric incisions on the surface (Callaway, 2014). While these shells can be debated to be considered art by historians, it’s important to note that long before the concept of “art” was created, homo sapiens were trying to do it (Figure 12.4).

The question “What is art?” is one that continues to be debated. Some art historians believe that the oldest piece of art to date has been discovered and originated from the Late Stone Age and the Upper Paleolithic Period, from between 70,000 and 40,000 BCE.

Figure 12.4. Prehistoric art carving, ca. 26,000 BCE.

Throughout history, art has been passed down from our families, rituals, and ceremonies that are given to us by our communities and interactions with the dominant culture (Breen, 2008). Do human beings have equitable access to create art now? Are there barriers that are present in the lives of individuals today that make it difficult or impossible to be able to engage in self expression? Systemic barriers that limit families in the United States from meeting basic needs also inhibit equitable access to self expression.

12.2.2 Using Art to Teach

Visual representations are strong; the popular saying, “a picture is worth 1,000 words,” speaks to this power. When it comes to teaching history in the high school setting, it has been found that art is a powerful pedagogy that moves students beyond the understanding that they gain from text alone. Students develop more interest in history, and the potential for examining multiple viewpoints via artistic representation can help students to develop critical thinking skills related to understanding history.

Younghee Suh summarizes much of the literature related to how students absorb history via artistic representations (visual, photographic, and musical among others) in the study, “Past Looking: Using Arts as Historical Evidence in Teaching History” (Suh, 2013). Suh focuses on pedagogy and notes that the way in which teachers expose students to art highly influences students’ abilities to sort fiction from fact. Exposure to art from the past is not enough, however. Teachers must also provide scaffolding to students that helps them to consider the perspective of the artist, the time in history, and the choice about which art is included in textbooks and other historical summaries. Without this guidance and contextualization, learners are left to see representations as “fact” instead of a particular viewpoint of the past.

Many history books (and the accompanying artistic representations) are presented from the viewpoint of the Euro-American settlers. It is important that we understand the experience of all families, not just the families who belong to the culture that now dominates. In the process of establishing dominance, Indigenous families were harmed. For example, children were frequently separated from the rest of the family and sent to schools where they were harshly punished for speaking their Native languages and practicing their religions (Little, 2018). Violence against Native women was and is still perpetuated at higher rates than against women of other races, and is underreported and under prosecuted (Amnesty International, n.d.).

Another example of the cultural context of art comes from Linn-Benton Community College in Albany, Oregon. A student made this observation in an art history class: “I took an art class and when my teacher was showing a painting of the Virgin Mary it seemed very normal to everyone in my class except for me, until she showed a picture of the Virgin Mary the way that Latinos are used to seeing her (the one on the left [a] in Figure 12.5 is a Mexican depiction of Virgin Mary and the one on the right is Italian [b]). If my teacher would have never said that it was Virgin Mary who was depicted in the art, I would’ve never known because that’s not how I have seen Virgin Mary growing up.”

Figure 12.5. Artistic representations of the Virgin Mary. A (on left) is part of a 16th century shrine located at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico City, Mexico. B (on right) is the Madonna del Granduca [oil on canvas] by Raphael, 1505, which hangs in the Pitti Palace, Florence, Italy.

The Virgin Mary is associated with qualities considered positively in Western culture, which include purity and beauty. Look closely at these images in Figure 12.4 to see how the expression of those characteristics are represented.

A discussion of art needs greater exploration and explanation, but the point of this section is to illustrate the ways in which art always has a viewpoint. While the dominant cultural viewpoint is the one most often seen, art can also be used to express other viewpoints and to initiate critical discussion about the past as we will explore in the next section.

12.2.3 Protest Art

Visual art as protest art is used both to promote and to express dissatisfaction with ideologies, policies, and social movements. Creative expression is used to express individual and group views, thoughts, and emotions. Because making art isn’t always an expensive venture, many can participate in it. Displays of art are not limited to inside the doors of a museum with admission fees. Anyone can access it while out and about in their daily lives; it is everywhere.

This brings us to the notion of power. When people express their thoughts and feelings via paper, canvas, media, or other outlets, it can have a powerful effect on an audience. Art that is expressed publicly is more equitably available to people in minoritized groups and with fewer socioeconomic resources.

Figure 12.6. Street art in Berlin, Germany of a portrait of George Floyd.

Figure 12.6 is a visual reminder of the number of Black men and women who have been killed by police when in helpless circumstances. The protest is not only about George Floyd’s murder, but also about the overall dominant culture of the police force in the United States.

Privileged groups who have a higher distribution of resources, such as wealth, may present their views via protest but also have the means to use art to catch people’s attention and promote their agendas via advertising, media, and political campaigns.

Art has a special place among activists and social movements because it can be used as a message to pay attention to a particular issue or injustice (Figure 12.7). It exists in part to freely express oneself and emotions, gain attention, plant a seed of thought, and inspire passion in some way, shape, or form to actively do something about the issue.

Figure 12.7. Gay Pride parade marchers holding signs.

Both protest and artistic expression are fundamental rights protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. The melding of the two creates messages that can influence and empower individuals and families. Artistic expression that protests and argues for power of the underserved is expansive, subjective, and cannot fit into any one box (Wikipedia, n.d.).

12.2.4 Public Art

Much of this chapter discusses art that has some kind of paywall: museums with entrance fees, or films and other media that require a ticket or subscription price. In this section, we will pay attention to art that may be considered “public” in one form or another. Public art is often defined as art that is “visually and physically accessible to the public” (Wikipedia, n.d.). While it is also often described as representing universal concepts rather than those that are partisan, political, commercial or personal, these authors challenge that notion from two perspectives. The first is that the funding for and decision-making about public art is still often controlled by dominant or political groups. While efforts have been made to equalize art-making decisions, the tension between money and ideals is real. Secondly, it can be said that all art is personal. What is more personal than an artist’s vision and creation? Some public art is commissioned by a public group, and this can come with restrictions or guidance for the artists. For now, we will stick with the definition that public art is art that is easily accessed by any member of society.

By its nature, public art may be viewed by anyone who can get themselves to the location it is presented. While it is more equitably accessible than art housed in museums, galleries, and media conglomerates, it is important to note that transportation, location, and resources (both time and money) prevent many families from accessing public art.

Creating and maintaining public art presents unique challenges to equity. Some citizens may hold art that is viewed and/or funded by the public to a different standard—one that emphasizes societal norms. Others may argue that some subjects are inappropriate to display publicly, in particular if children or young adults could view the display.

12.2.4.1 In Focus: Linn-Benton Community College and “Drawing the Line”

The tensions that can exist around public art displays were demonstrated during the 2017 exhibit “Drawing the Line” in the hallways of North Santiam Hall at Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC). Curated by LBCC Art faculty and students, the fiber art of Andrew Douglas Campbell lined the halls through which the LBCC community traversed to class, the lunch commons, and offices (figures 12.7 and 12.8). Generally, Campbell explores themes of difference, connection, and identity in his work. He is an artist who merges the mediums of photography and fiber to focus on the response and interaction of social and narrative tensions. To read more from Campbell, view his website here.

Figure 12.7. Rend and Mend by Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

The public art display at LBCC explored multiple subjects, but attention rapidly became focused on one series that examined the relationship of the porn industry and its marketing strategies to the queer community, titled “… And Then What Could Happen Bent to What Will Happen…” seen in Figure 12.9. The series is pictured here, on Campbell’s website.

Figure 12.8. Thresh(strand)hold by Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Campbell describes his process: “[I was] thinking about the porn industry as a market that I personally had not yet held with the same skeptical eye as I do a lot of other economies, and so I started to look at that and part of it is true, they have tapped into a certain desire of mine. Part of it is I’m very skeptical of it,” said Campbell. “It made sense to me that I should render their material sort of inconsequential; it’s so fragile it can be blown away. It’s important but unimportant at the same time, it’s present and not present, it’s solid and transparent. That’s where I came up with these very loose airy images that are barely there but still very impactful” (Guy, 2017).

Figure 12.9. “…and then what will happen bent to what could happen…” by Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

The focus became negative; a local company that pays their employees’ tuition at LBCC and a member of the Board of Directors of the College were most outspoken in their belief that this work should not be displayed in a setting that was publicly accessible. There were discussions about this display at every level of the college: in offices, classrooms, and boardrooms. Ultimately, there were some alterations and adaptations to the exhibit, and it remained in place.

When considering the diverse structure and viewpoints of families in the United States, it is important to think about whether all families have access to viewing art that speaks to them, represents them, and inspires them. Limiting art to the viewpoint of any dominant group limits the expression and growth of families. “Drawing the Line” is the catalyst for related questions: would similar artwork that expressed heteronormative experiences have invited the same controversy? And why is sexuality considered an offensive or inappropriate subject for public artistic display, and yet scenes of conquerors, violence, and dominance are prominently exhibited? Examples of and responses to the latter will be discussed in the next sections.

12.2.4.2 In Focus: Bellevue Community College Mural

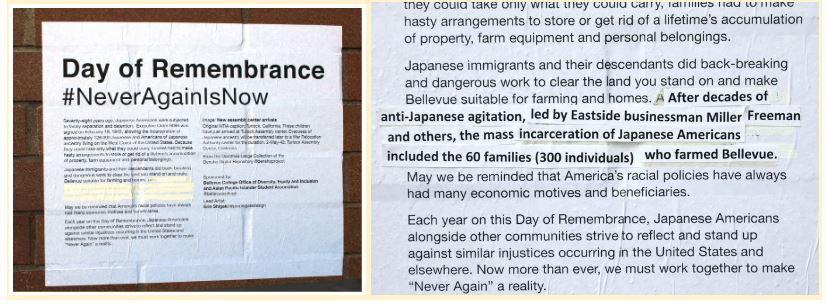

In an example of the clash between the dominant culture and the portrayal of a discriminatory act at Bellevue Community College in Seattle, Washington, several administrative leaders lost their jobs when they bowed to pressure to alter the artist’s statement on a public mural (Figure 12.10). This is a literal example of whitewashing history, as white-out was used to eliminate the names and racially-ethnically based actions of a prominent citizen in March 2020.

Figure 12.10. These images show us a concrete example of “whitewashing” (A) and then the pasted over corrections of the original artist’s statement (B).

More will be written about this event in future editions of this text, but here are links to the articles describing what happened and what consequences occurred:

12.2.5 Access to Art and Culture

Families have unequal access to viewing and experiencing visual culture. Geographical location, socioeconomic status, and social characteristics all influence access to art. In particular, families in rural areas, with lower socioeconomic status, and in minoritized groups have less opportunity to accrue wealth in the United States and have fewer opportunities. In addition, they are less likely to have influence in terms of what is considered worthy to appear in curated exhibits behind museum doors.

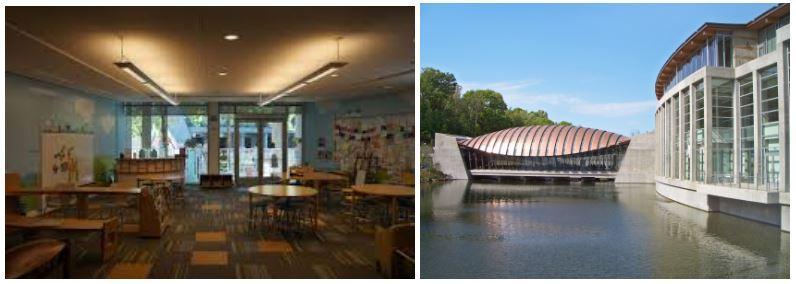

One way to measure equity in art is to examine the ability to view curated art. Access to art in childhood is especially important because activating the developing child and adolescent brain impacts eventual life outcomes. In 2011, a unique opportunity presented itself to study how child access to art affected adult outcomes. Alice Walton, a Walmart heir, founded the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, a 50,000 square-foot space with an 800 million dollar endowment, in Bentonville, Arkansas (Figure 12.11). Most children in this area had little or no exposure to art or other cultural experiences.

Class visits were provided for free via the gift of a donor. Demand was high, and not all groups who desired the visits could be accommodated. Scholars from the University of Arkansas set up a lottery system to determine which school groups would visit the museum. During the following months, all students (those who visited and those who did not) were offered free tickets to visit the museum with their families, and were also administered a multi-dimensional survey. Nearly 11,000 students and 500 teachers participated in this study (Green et al., 2013).

Figure 12.11. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art; both images from Wikimedia Commons.

Students who visited the museum with their classmates demonstrated stronger critical thinking skills, displayed higher levels of social tolerance, exhibited greater historical empathy and developed a taste for art museums and cultural institutions (Kisida et al., 2013). In addition, students who had visited the Museum with their class groups were 18 percent more likely to use the coupon to visit the Museum with their families! Importantly, this effect was stronger for minority students, rural students, and low-income students than it was for White, middle-class, suburban students. While there are additional questions to be answered, this study demonstrates the importance of exposure and access to art and cultural experiences for all children. The study indicates that arts education inclusion in school curricula will help students develop critical thinking, an understanding of diverse ideas and experiences, and empathy with those who are different from themselves.

12.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Experience, Expression, and Equity

12.2.6.1 Open Content, Original

“Experience, Expression, and Equity” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Christopher Byers, and Carla Medel is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Art: An Historical Context” by Christopher Byers by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Using Art to Teach” and “Public Art” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Protest Art” by Carla Medel is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

12.2.6.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 12.1. Photo of street art in Medellin, Colombia. CC0.

Figure 12.2. “Water Lily Pond” by Claude Monet. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 12.3 Storage basket [Apache],ca. 1890, The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art, Gift of Charles and Valerie Diker, 2019, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public Domain.

Figure 12.4. “Stone Age Animal Carving, Hayonim Cave, 28000 BP” by Gary Todd (photographer). CC0.

Figure 12.5. Juxtaposition of two images of the Virgin Mary: “Virgen de guadalupe” and “Madonna del Granduca” by Raphael. Public domain.

Figure 12.6. “Mural portrait of George Floyd by Eme Street Art in Mauerpark (Berlin, Germany)” by Singlespeedfahrer (photographer). CC0.

Figure 12.7. Photo by Pxfuel. License: Pxfuel license.

Figure 12.11. “The Experience Art Studio at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas (United States)” by Michael Barera. License: CC BY-SA 4.0. “Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas USA, architect Moshe Safdie, photo of one of three bridge pavilions” by Charvex. CC0.

12.2.6.3 All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 12.7. “Rend and Mend” (c) Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 12.8. “Thresh(strand)hold” (c) Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 12.9. “…and then what will happen bent to what could happen” (c) Andrew Douglas Campbell. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 12.10. Erin Shigaki’s statement about her installation at Bellevue College is shown after a sentence was removed that references anti-Japanese views held by Miller Freeman and other Eastside businessmen in the decades leading up to…(Courtesy of Leslie Lum)(A) and the sentence removed from Erin Shigaki’s statement accompanying her art installation at Bellevue College has now been replaced. (Greg Gilbert / The Seattle Times)(B) from The Seattle Times, February 26, 2020. All rights reserved. Used under fair use.

12.2.7 References

Mirzoeff, N. (1998). What is visual culture? In N. Mirzoeff (Ed.), The visual culture reader (2nd ed., pp. 3-13). Routledge.

Callaway, E. (2014, December 3). Homo erectus made world’s oldest doodle 500,000 years ago. Nature News. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2014.16477

Breen, R. (2008, November 26). Towards a collective understanding of art as a commons. On the Commons. http://www.onthecommons.org/towards-collective-understanding-art-commons

Suh, Y. (2013). Using arts as historical evidence in teaching history. Social Studies Research and Practice, 8(1), 135-159. http://www.socstrpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/MS_06372_Spring2013.pdf

Little, B. (2018, Nov. 1). How boarding schools tried to ‘kill the Indian’ through assimilation. History.com. https://www.history.com/news/how-boarding-schools-tried-to-kill-the-indian-through-assimilation

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Maze of injustice. Retrieved February 26, 2020, from https://www.amnestyusa.org/reports/maze-of-injustice/

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Protest art. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protest_art

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Public art. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_art

Guy, S. (2017, October 25). Drawing the line: Artist Andrew Douglas Campbell speaks on behalf of his controversial work. The Linn-Benton Community College Commuter. http://lbcommuter.com/drawing-the-line-artist-andrew-douglas-campbell-speaks-on-behalf-of-his-controversial-artwork/

Green, J.P., Kisida, B., & Bowen, D.H. (2013, September 16). The educational value of field trips. Education Next, 14(1). https://www.educationnext.org/the-educational-value-of-field-trips/

Kisida, B., Green, J.P., & Bowen, D.H. (2013, November 23). Art makes you smart. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/24/opinion/sunday/art-makes-you-smart.html