4.6 Socially Constructed Ideas: Form and Function

Elizabeth B. Pearce

This text began with a chapter about ideas that are socially constructed, including the picture of the traditional, or ideal family. That nuclear family model, often represented as two white married heterosexual middle-class parents with 2.2 children, is only one form of families involving caregiving and sometimes children. In this section we will distinguish between family form and family functionality.

Figure 4.22. Family structure, or form, is separate from the health of the family, or the family function.

Families come in many forms, including those described above, many variations of adults with children, and those without children. Family forms include parents who are married, living together, divorced, stepparents, adoptive parents, single parents, grandparents in parenting roles and foster parents. Forms may include blended and step families, half-siblings, and step-siblings. The form of any household may include more than two generations or people who are not related legally or by blood. All of these are differing forms, or structures of family life. The family form is merely the physical makeup of the family members in relationship to one another. These differing forms are sometimes called the “complexities” of family life in academic literature. The form does not indicate how healthy the family is, or how well the family members behave toward one another, known as the family function.

Families function in a range of ways and differently over time. How well does any given family function? That answer is complicated to measure in one moment and also over time. It includes the functionality of each individual family member, the functionality of any two members’ relationship, and the overall functionality of the entire family. What indicates healthy functionality? Here are a couple of indicators; you may have your own standards of what indicates healthy functioning.

- Respect for the individuality of each family member

- Communication that is direct, but not purposefully harmful or painful

- Commitment to each other

- Parent(s) who prioritize their children’s needs

Figure 4.23. Family forms have developed and changed over time, and there is no one typical family structure.

It is important to understand and to separate form and functionality. Because many of our social institutions identify one kind of family as “the norm” it is easy to assume that somehow other kinds of families are “less than.” That is not the case. As discussed throughout this text family forms have developed and changed over time. It is critical to note that there are many well functioning families that include single or gay parents, or who are poor, who have been incarcerated, who have lots of children, or have no children. All families face challenges, and families that look “perfect” on the outside may have dysfunctions. As you navigate the world, do your best to remind yourself of this, because the societal message is often the opposite.Throughout this chapter we discuss families who may not fit that idealized family form, but who are just as likely to have loving functional relationships within their family.

4.6.1 Families without Children

Increasing number of partnered adults are completing their families without having children. As discussed earlier all three rates (birth, fertility, and fecundity) are declining. In this section, the authors wish to acknowledge the societal stigma that can be associated with not having children.

4.6.1.1 Childless or Childfree?

For many decades in the United States, there was a predictive life course for heterosexual, white, middle-class families. This was considered the ideal, and a part of the “American Dream.” Steps included going to school, starting a career, getting married, and then “starting a family,” which really meant having children. Couples were expected to produce babies soon after marriage.

But this norm, never attainable for all families, has become increasingly diversified. Now it is known that a family can be a “family” without including children. There is greater awareness of the difficulties that a heterosexual couple may have with conceiving a child. There is greater acceptance of same-sex couples who may have difficulty adopting or using medical and biological means to procreate. And there is increased understanding of couples who do not wish to have children and consider their families complete without children. These families express their desire to remain childfree by choice.

Increased awareness and acceptance does not equate with a disappearance of social stigma. Harmful viewpoints that equate pregnancy with “becoming a woman” or that describe men being more masculine if they get someone pregnant quickly continue to resonate in our society, along with the idea that one’s life is not “complete” until they have children.

4.6.2 Same-Sex Parenting

Pearce/Franco

LGBTQ+ parenting refers to the care and guidance of children with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer couples along with other members of this broad community. People who identify within this community can become parents through various means, including – but not limited to – adoption, foster care, insemination and other pregnancy methods, and surrogacy.

LGBTQ+ identifying parents have been proven to be as effective as heterosexual parents (although this comparison in and of itself reflects the binary hetero-normative standard, itself a social construction.) The primary research in this area has been conducted on same-sex parents. This research was originally driven by the desire for data when parents divorced and one parent identified as gay. Both heterosexual and LGBTQ+ parents sought rationales that would justify the child custody arrangement that they preferred.

Judith Stacey and Timothy Biblarz are known for their 2001 literature survey and analysis of research related to LGBTQ+ (then called “lesbigay”) parenting. There are no notable differences in the major markers of parent-child relationships or of child health when children raised by same-sex parents are compared to children raised by heterosexual parents; both psychological and physical development of children are comparably healthy (Stacey & Biblarz, 2001). Children raised in LGBTQ+ households tend to hold more open views about gender and sexuality identities than do children raised in heterosexual families. Stacey and Biblarz go on to argue that such comparative studies only serve to reinforce the framework that sexual orientation is a significant aspect of parenting, and that research focused on other parenting differences such as gender, parent-child involvement, and processes such as divorce or adoption would better serve the social science research.

An argument against LGBTQ+ parenting has been made that children will face bullying and harassment in either the public arena, or in court cases involving child custody. It is true that these families face marginalization and discrimination. Is this a reason to deny these families their rights, essentially marginalizing them further? These authors argue that like other families from marginalized groups, it is the work of social institutions and society to diminish and eliminate the causes of discrimination.

4.6.3 Student Parents

Parents who are also students live at the intersection of two social constructions that don’t quite fit them. First, they often do not fit the demographic of the “traditional college student” which the Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis describes as “someone who begins college immediately after high school, enrolls full-time, lives on campus, and is ready to begin college level classes” (Deil-Amen, 2011). While community colleges have long served the “nontraditional” student population, universities are more recently adapting to this student group and the ways that their needs differ.

Secondarily student parents may not fit the socially constructed family ideal either, at least in terms of how a paying job or career fits into their family life. They are likely to have a family where “all adults are working” meaning that whether single or coupled, someone(s) has paid employment in addition to a college career. This creates immediate conflicts in prioritization, because they are not only “balancing work and family” but likely “school, work, and family.”

The COVID-19 pandemic hit this group of families particularly hard as their multiple work, schooling, and children’s environments collided. Students often work in lower-paying industries while going to school to better their situations for themselves and their children. Those settings and jobs were often eliminated when locations such as restaurants, bars, and other service industries were shut down. In other cases work at places such as food production and canning, grocery stores, or medical settings were still open but brought higher risk of infection. Schools from child care settings to college settings were unpredictable in their hours and services. Student parents have been in a constant state of planning, responding, and trying to survive in environments compounded by uncertainty.

4.6.4 Foster and Adoptive Families

One way to protect children from abuse or neglect is to remove them from their primary caregivers and place them into foster care or with family members. (Child safety, neglect, and abuse will be discussed more thoroughly in the Safety chapter.) Foster care is regulated state by state, but generally consists of a system in which a minor is placed into a private home of a state-certified caregiver, referred to as a “foster parent,” with a family member, or occasionally in a group setting approved by the state. The placement of the child is arranged through the government or a social service agency. The state, via its Child Services department maintains responsibility for the child.

In the United States the number of children in foster care has steadily grown between 2010 and 2019 from about 405,000 to roughly 424,000 according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2019 AFCARS Report. The number of children waiting to be adopted is 122,000 as of September 2019. This means that these children’s parents have lost the legal rights and custody, leaving them without any permanently legal caregivers (the government assumes this responsibility until someone adopts the children). The average age of youth waiting to be adopted from foster care is eight years old.

4.6.5 Families with Disabled Members

Disabled people have always faced problems which are created because society is structured without disability in mind. For instance, the rail transport system assumes that all passengers can step over a gap between a train and the platform, that they can walk to their seat, and indeed that sitting in a “standardized” seat is an option. There are countless practices in our study which exclude or marginalize disabled people. The way things routinely get done in everyday life can be problematic, and that can include the material infrastructure of a building as well as the ways in which people interact. For instance, people with dementia might rely on familiar, clear signage to find their way in and out of a building, or the facilities in it, but they also need people who will give them time to communicate, or understand how to wait for a response in a respectful way.

How can we start to understand the ways that social structure interacts with families who have members with disabilities? It is important to understand the dichotomy between the social and medical model of disability. The medical model, which has dominated thinking in the United States, focuses on the individual who has a difference in ability as having a personal problem. The social model focuses on society and culture making adjustments that allow all people to access activities and services.

Figure 4.24. The first image focuses on the individual having a problem. The second image shows how an adapted environment can contribute to equity in access.

The social model directs our attention towards the external barriers facing disabled people, and now we need to find better ways of analyzing and understanding those barriers. It also emphasizes that people who have a disability can be active participants in what kinds of societal supports and policies will be effective.

An individual disabled family member affects all other members of the family as well as the overall family dynamic. Parents and caregivers must respond to the child who faces more systemic challenges to participating in daily life. While there are services and funding available for families, there is not a centralized system, forcing families to spend valuable time and financial resources to apply for these assets. Many parents believe that the available resources are not sufficient. Admittedly, if parents need to focus on one child accessing basic activities such as school, health care, or transportation, they may have less time or financial resources for their other children or partners.

Caring for adults, such as siblings, close friends, or parents also affect family dynamics. When those adults are able to find support that removes society’s barriers it can positively affect the rest of the family. As people are living longer, the number of adults who face Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia are increasing.

Here are some words from the Forget-me-Not dementia group in the United Kingdom:

Everyone will tell you the same thing. You’re diagnosed, and then it’s “You’ve got dementia. Go home and we’ll see you next month.” What we need is for someone, like a counselor or someone else with dementia, to tell us at that point “Life isn’t over.” You can go on for ten or fifteen years. And you’re not told, you’re just left. And I thought, tomorrow my day had come. The fear and the anxiety sets in, and then the depression sets in, doesn’t it? I think when you’re diagnosed, you should be given a book. And on the front of the book, in big letters, it should say: “Don’t panic.” (Forget-me-not club—Dementia support, n.d.)

These are people who do not want to be seen through a medical lens as individual tragedies, but are turning around the whole meaning of dementia into something where they are in control, can support each other and where they have a voice. However, social practice theory also reminds us about the importance of material resources. For instance, in order to meet each other and to have a collective sense of peer support, people need to have spaces which are not institutionalized, which they feel they can ‘own’. All too often, we have seen very well-intentioned group activities taking place in old, large halls, or where people are routinely sitting in configurations which make communication difficult. But we have also seen the Forget-me-Not group, in an ordinary, homely environment, where staff members interact on a basis of equality with the members who have dementia.

This is just one of many examples where we are finding that people CAN do things differently, and where society can change towards inclusion and empowerment.

4.6.5.1 Dreaming of JuniperHailey Adkisson, M.A., Communication,North Dakota State University; B.S.Media Art and Design, James Madison University; Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC) Communications Faculty. |

| When you have children, you have certain dreams for them. There are big ones like going to college, getting married, having their own children. There are smaller ones, like first steps, teaching them to ride a bike, or shopping for a prom dress. But what happens when those dreams can’t become a reality? How do we celebrate our children for who they are while still allowing ourselves the ability to mourn our dreams?

Figure 4.25. Juniper in a sun hat, playful and silly. When Juniper was six months old, we noticed she was exhibiting some strange movements; her arms would jerk up, her body would crunch, and her head would dip. At first, it would happen every few days in a cluster of 5-10. Just later, these movements began happening at every sleep/wake cycle and lasted 20-40 at a time. Maybe it’s reflux? Maybe it’s a weird baby movement? We contacted her pediatrician just in case and were told if she was breathing regularly, it wasn’t an emergency. Something told me this wasn’t quite right and we drove to the nearest emergency room for another opinion. The ER doctors saw Juniper having the movements, but like her pediatrician, told us not to worry. I tried to reassure myself of this as we drove an hour to the nearest children’s hospital the next day, but I knew in my gut, something was seriously wrong. Juniper was hooked up to an electroencephalogram (EEG) to test for abnormalities in her brain waves. When the attending physician came into the room, the look on his face told me it wasn’t good news. Juniper was diagnosed with a rare and catastrophic form of pediatric epilepsy called Infantile Spasms (IS). Each movement we were seeing was actually a tiny seizure, and she was having hundreds a day. In addition to seizures, her background brain activity presented in a pattern called hypsarrhythmia. Think of this as static on a radio. It’s hard to comprehend the story because the static keeps interrupting the message. Additionally, each seizure was as if her brain was “rebooting” like a computer. Shutting down, then starting back up. If we didn’t stop the hypsarrhythmia and the spasms, Juniper would not be able to develop because she wouldn’t be able to encode anything she was experiencing or learning. Her brain would be too cluttered. The outcome of IS on children largely depends on how they respond to treatment and what the underlying cause of the seizures are. Epilepsy is a symptom of something else; genetic variations, metabolic syndromes, a traumatic brain injury, or brain malformations. A child could respond quickly to treatment, but they could have a genetic variation that causes intellectual and physical disabilities in the future. First, stop the spasms. Then, figure out the cause. Juniper was prescribed an extremely high dose steroid treatment we injected into her chubby baby thighs twice a day. My beautiful and happy baby gained five pounds in a month and was miserable. Unfortunately, it didn’t stop the spasms. Another medication with horrible side effects, another relapse. At this point, we decided to get a second opinion and it was discovered that Juniper’s cause was a malformation called focal cortical dysplasia (FCD). Juniper celebrated her first birthday hooked up to an EEG. Four days later, she underwent a hemispherectomy. This aggressive surgery involves removing half her brain. The hope being that removing the dysplasia while young would allow her brain to rewire. While we may be able to achieve seizure freedom, it didn’t come without a cost. Juniper would lose vision on the left side of both her eyes. She would have paralysis in her left arm and left leg and would never have fine motor skills in her left hand. She would likely have trouble with numbers, memory, self-control, and emotion regulation. Her chance of autism increased. She may be nonverbal.

Figure 4.26. In the hospital bed, Hailey and Juni snuggle. As a parent, you make decisions on behalf of your child every day in hopes of providing them with the best quality of life. While our decision was one I wish no other parent ever has to make, our goal was still the same; we needed to give Juniper a chance at the best quality of life, and that meant surgery. But what is a “good” quality of life? For Juniper, it can’t be based on our “norms”—a house, a good job, financial security, a marriage, 2.5 kids and a Labrador. So is it mobility? Independent feeding? Verbal communication? What if that isn’t her reality? Does that mean she has a bad life? How do I know if my daughter has a good life? To know, I have to ask myself: Is she happy? Is she comfortable? Is she safe? Constant seizures would not allow her to have any of these things. While I don’t know what Juniper will be able to do in the future, there are some obvious limitations. When my son asked if Juniper would be able to have babies, I cried. These are not Juniper’s dreams, they are mine. My children are an extension of my own dreams. While I hope she never feels a loss of anything, that she thinks her life is beautiful and amazing, I will feel that loss. Like any loss, it will take time to grieve. It’s hard to explain what it is like to have a child with a disability. You love them fiercely and are amazed by them every day, but you also mourn what could have been. You get to celebrate every tiny thing, moments I missed with my son because they happened so quickly. At the same time you wish life wasn’t so challenging for them and that things like “pushing to sit” came naturally. The uncertainty about Juniper can be incapacitating at times because there is so much we don’t know. What I do know is that she has changed me. I am stronger than I thought I was. I am more resilient. I learned how to advocate for my child; look a doctor in the eyes and demand a plan. I learned the importance of trusting my gut when it comes to parenting. I often think back to what would have happened if I had brushed off my intuition in those early days of her diagnosis. Juniper looked and acted like a “normal” baby. Even after her spasms became more intense and I documented an episode on video, her pediatrician at the time and an entire team of ER doctors told us not to worry— it was no big deal. The truth is, IS is an emergency. It is an extremely rare and catastrophic form of epilepsy that often goes misdiagnosed for months (even by medical professionals). If left untreated, IS can have devastating impacts on development. Most importantly, I have learned to appreciate tiny moments of joy that I never slowed down to see before. While I still experience deep grief about the trauma my daughter and my family has had to go through, I try to stay focused on the present as much as possible. Yes, my dreams for my daughter have had to shift. Instead of mourning what she won’t be able to do, I try to focus on who she is now.

Figure 4.27. Juniper has wonderful happy times with her family, as well as big challenges. Juniper has a smile that seems too big for her face, and a belly laugh that fills an entire room with joy. She loves being outside, especially when she is in her swing. She will grab at any necklace, watch, or shiny thing within reach. There isn’t a food she dislikes. She’s addicted to her pacifier. Her brother is her favorite person. Juniper is more than her disability. She is more than her seizures. She is more than her brain surgery. Her journey hasn’t fit with the dreams I had for my children, but dreams change. They have to. Otherwise, you’ll miss out on the beautiful reality that’s right in front of you.

Figure 4.28 Hailey and Juniper Hailey Adkisson, M.A is a full-time community college professor, a wife, a mother of 3, and in her “free time,” an unofficial therapist, nurse, and pharmacist to her daughter, Juniper, who has med-resistant epilepsy. Since her daughter’s diagnosis, Hailey has immersed herself in the disability community, connecting with families across the country who have young children with medical complexities. She believes building community is key to providing support for parent caregivers like herself. You can reach out to Hailey on @growing_juniper on Instagram. |

4.6.6 Poverty

Throughout this textbook, you will read about how families who experience poverty are impacted in terms of their daily needs: housing, food, water, education and more. Each chapter will delve into one of these specific needs and highlight how socioeconomic status combined with other social characteristics such as sex, gender, race, and ethnicity contribute to intersectionality and the likelihood of discrimination.

But how does poverty affect the public function of caregiving in families?

As highlighted in earlier sections of this chapter, it has been found that socioeconomic status, more than race or ethnicity, has been identified as a key indicator in the ways that parents raise their children. Why this is so, is a difficult question to answer. It can be deduced that parents with a higher socioeconomic status have more resources and therefore more choices about where they live and what activities their children are involved in.

Does this make their parenting or their love for their children superior? Of course not. But it does tell us that they may be able to afford options for their families that others cannot. The effects of poverty affect family dynamics in at least two ways. First, because in reality “time is money” parents who are poor often have less time as well as less money. So they have less time to spend with their children. Secondly, because they are at the lower end of “classism”, they are more likely to be discriminated against based on socioeconomic status than other families.

Families in lower socioeconomic groups face more judgment and discrimination. Parents in these groups may have to make more difficult choices with both time and money such as “Should I make a home-cooked meal, or should I sit on the floor and play with my child—which means I have to serve a frozen meal?” Even that choice may create more choices, as a prepared frozen meal will likely cost more than something that takes time to assemble. “Should I pay for this needed car repair or for a new pair of shoes for my child?” presents related dilemmas. Enter the societal culture that judges parents on what can be seen: worn out shoes or new shoes?

In this text, we will continually look for systemic solutions to social problems such as the numbers of families in the United States who experience poverty. Enlightening research tells us that it is possible to impact families positively via social programs. A recent study led by Columbia University in New York, demonstrates the effect of cash gifts to poor families:

“This study demonstrates the causal impact of a poverty reduction intervention on early childhood brain activity. Data from the Baby’s First Years study, a randomized control trial, show that a predictable, monthly unconditional cash transfer given to low-income families may have a causal impact on infant brain activity. In the context of greater economic resources, children’s experiences changed, and their brain activity adapted to those experiences…

Early childhood poverty is a risk factor for lower school achievement, reduced earnings, and poorer health, and has been associated with differences in brain structure and function. Whether poverty causes differences in neurodevelopment, or is merely associated with factors that cause such differences, remains unclear. Here, we report estimates of the causal impact of a poverty reduction intervention on brain activity in the first year of life…

In sum, using a rigorous randomized design, we provide evidence that giving monthly unconditional cash transfers to mothers experiencing poverty in the first year of their children’s lives may change infant brain activity. Such changes reflect neuroplasticity and environmental adaptation and display a pattern that has been associated with the development of subsequent cognitive skills.” (Troller-Renfree et al., 2022)

This study lends hope that the cycle of poverty can be interrupted. Policies and programs that contribute to equity can make a positive difference in the outcomes for families experiencing poverty.

A recent federal policy demonstrates a practical application of cash benefits. In the American Rescue Plan of 2021, the Child Tax Credit was not only expanded, but also distributed differently. Prior to 2021, parents received the child tax credit in a lump sum, after submitting their taxes. Many expenses related to having children, such as child care, rent/mortgage, transportation, and extracurricular activities are payable by month or by week—not in one lump sum. But in 2021, families received a monthly distribution of about $250-300/month (“The Child Tax Credit,” n.d.). Not only was monthly income predictable, it was also expanded to the poorest families, those who do not pay income taxes, who were previously excluded from this benefit. Unfortunately, the extension of this program is included in the now stalled Build Back Better agenda that has not been passed by the U.S. Senate as of February 2022.

4.6.7 Pandemic Parenting

It is difficult to imagine a more life-altering period of time than that of the COVID-19 pandemic that spans late 2019 to the present day. If we look back at the Ecological Systems Theory, this pandemic qualifies as a chronosystem large socio-historical event that ripples inward through the concentric circles of families’ lives. It has affected the cultural practices of our macrosystem (such as wearing masks and social distancing); it has changed exosystem elements such restaurants, stores, and places of worship; it has dramatically altered our microsystem settings such as workplaces, schools, and perhaps even our homes. And what of the mesosystem, the connections and relationships between all of these systems? Well, by inference, those have been changed as well.

Large catastrophic events are known to be linked with mental health burdens. Caregivers are not exempt from these mental health changes; in fact they may be greater than for those who are not caring for others. While the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are unknown, it is likely that individual and family outcomes will be changed. Already it is known that K-12 and college students are experiencing much higher levels of depression (“The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Mental Health,” 2020). With people of all ages experiencing mental health challenges, it is likely that it will affect the parent-child relationship, or any caregiving connection.

4.6.7.1 Women, Work and Parenting

In addition, the pandemic has affected parents, especially mothers, in their work life. The transition to online schooling and stay-at-home orders during the coronavirus pandemic required at least one adult in the home to focus on the children—helping them with schoolwork and supervising them all day.

While there was no immediate impact on detachment or unemployment, working mothers in states with early stay-at-home orders and school closures were 68.8 percent more likely to take leave from their jobs than working mothers in states where closures happened later, according to new research by the U.S. Census Bureau and Federal Reserve (Heggeness, 2020). While one study found that dads increased their childcare role during the pandemic, it also showed moms spent the most time caring for children (Sevilla & Smith, 2020).

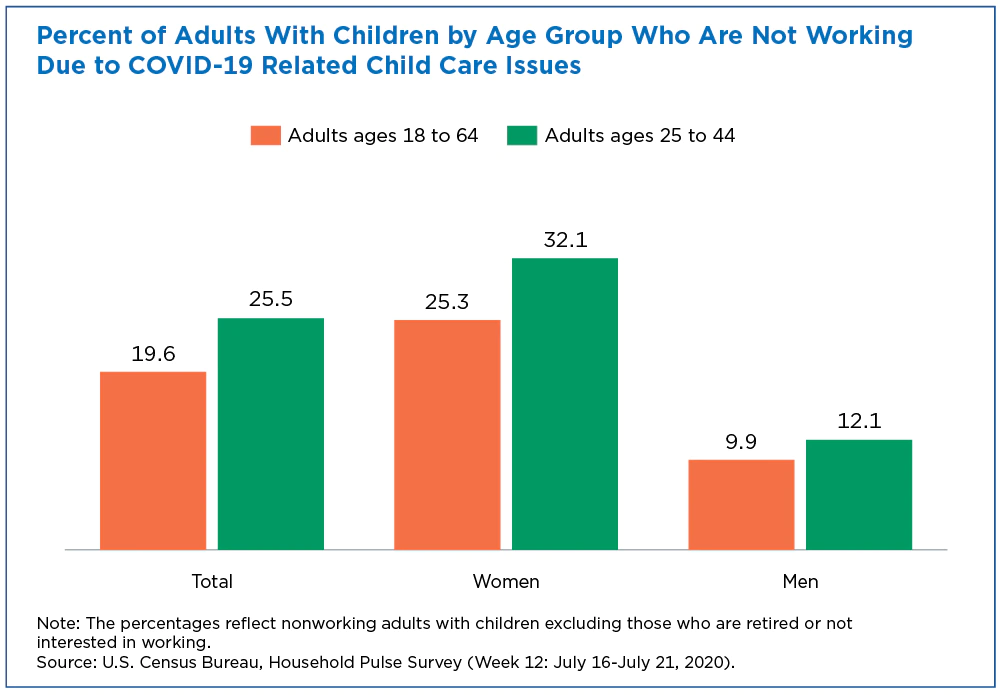

In the United States, around one in five (19.6 percent) of working-age adults said the reason they were not working was because COVID-19 disrupted their childcare arrangements as shown in Figure 4.28.

Figure 4.29. This graph clearly illustrates the effects of the pandemic on working mothers.

4.6.7.2 Caregivers at Home; Caregivers at Work

Working parents in all fields face the challenge and stress of balancing their work lives with caring for their children, as well as other personal and household responsibilities. In this section we will focus on a subset of working parents who have elected to work in jobs or careers that are focused on serving others. These fields include education, health, human services, and hospitality.

In all of these fields there is an emphasis on serving others and to some degree a focus on a cause greater than oneself. For example, teachers are focused on creating a curriculum and an environment in which students achieve specific learning outcomes. At the same time, they are concerned with their students’ overall well being. They work with 25 to 150 students each year, depending on their teaching assignments, with a societal expectation that all of these students will succeed.

How does being service oriented in one’s work life overlap with nurturing when also a parent?

It is undeniable that the collapse of many public systems during the pandemic affected this group of caregivers powerfully, putting many of them in a public bind. Teachers who are caregivers at home faced both the immediate need to completely adapt their curriculum into online and video conferencing content at the same time, arranging for their own children or dependents to adjust to lack of in-person services. Many times they were teaching their own children at home while responsible for the learning of a group of other students. Health workers faced the onslaught of more people needing medical care and the psychological component of being exposed to a deadly disease on a daily basis. They faced the lack of schooling, child care, and adult day services for their own dependents, while facing an increased demand on their work time.

Even in non pandemic times caregivers face the challenge of providing self-care while caring for others. While the pandemic exacerbated this dual challenge, it is one that is always present for this group of parents and other caregivers.

4.6.8 Licenses and Attributions for Socially Constructed Ideas: Form and Function

4.6.8.1 Open Content, Original

“Socially Constructed Ideas: Form and Function” and all subsections except those noted below by Elizabeth B. Pearce are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Same-sex Parenting” by Shyanti Franco and Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Dreaming of Juniper” by Hailey Adkisson is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.25 “Juni in Sun Hat” by Hailey Adkisson is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.26 “Hospital Snuggles” by Hailey Adkisson is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figures 4.27 (a) and (b) “Juni at home” and “Juni on the Move” by Hailey Adkisson are licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.28. “Mother-Daughter” by Hailey Adkisson is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

4.6.8.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

“Families with Disabled Members” includes an excerpt from Disability Needs to be Central in Creating a More Just and Equal Society in Comment and analysis from the School for Policy Studies by Professor Val Williams that has been edited and combined with original paragraphs focused on the United States by Elizabeth B. Pearce and used under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Figure 4.22 “A genderfluid person and a transgender woman practicing tarot” by Zackary Drucker and The Gender Spectrum Collection is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.23 Father, walking, nature by Laubenstein Ronald, USFWS on PIXNIO is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.24. A wheelchair user’s problems being caused by an inaccessible environment by MissLunaRose12 and used under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 4.29. Women, Work and Parenting is from Parents Juggle Work And Child Care During Pandemic from the United States Census Bureau and is in the public domain.

4.6.9 References

Forget-me-not club—Dementia support. (n.d.). Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.forgetmenotclub.co.uk/help.html

Heggeness, M. (2020). Why is mommy so stressed? Estimating the immediate impact of the covid-19 shock on parental attachment to the labor market and the double bind of mothers | opportunity & inclusive growth institute. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.minneapolisfed.org:443/research/institute-working-papers/why-is-mommy-so-stressed-estimating-the-immediate-impact-of-the-covid-19-shock-on-parental-attachment-to-the-labor-market-and-the-double-bind-of-mothers

Sevilla, A. and Smith, S. (2020). Baby steps: The gender division of childcare during the COVID19 pandemic. University of Bristol.chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.bristol.ac.uk/efm/media/workingpapers/working_papers/pdffiles/dp20723.pdf