4.4 Child and Family Theories and Perspectives

Elizabeth B. Pearce; Shyanti Franco; and Genna Watkins

There are several important and well-accepted theories about how children develop. While we cannot describe all of those theories in this text, the authors will point you toward the Thriving Development texts to examine multiple theories. In this text we will describe Psychosocial Theory (Erik and Joan Erikson), the ecological systems theory (Urie Bronfenbrenner) as well as several parenting and attachment frameworks.

4.4.1 Psychosocial Theory

The psychosocial model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life. The theory emphasizes our relationships and that society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior and the importance of conscious thought.

This model focuses on the importance of culture in parenting practices and personal motivations. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

The theory divides the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erik Erikson, the psychologist who developed this model, included three stages of adult development as well; his wife Joan Erikson added an additional stage following his death. Both theorists believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living. Figure 4.12 shows a brief overview of the theory including the ninth stage of development.

| Name of Stage | Description of Stage |

|---|---|

| Trust vs. mistrust (0-1) | The infant must have basic needs met in a consistent way in order to feel that the world is a trustworthy place. |

| Autonomy vs. shame and doubt (1-2) | Mobile toddlers have newfound freedom they like to exercise and by being allowed to do so, they learn some basic independence. |

| Initiative vs. Guilt (3-5) | Preschoolers like to initiate activities and emphasize doing things “all by myself.” |

| Industry vs. inferiority (6-11) | School aged children focus on accomplishments and begin making comparisons between themselves and their classmates |

| Identity vs. role confusion (adolescence) | Teenagers are trying to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles, beliefs, and ideas. |

| Intimacy vs. Isolation (young adulthood) | In our 20s and 30s we are making some of our first long-term commitments in intimate relationships. |

| Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood) | The 40s through the early 60s we focus on being productive at work and home and are motivated by wanting to feel that we’ve made a contribution to society. |

| Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood) | We look back on our lives and hope to like what we see-that we have lived well and have a sense of integrity because we lived according to our beliefs. |

| Revistation of Stages (elderly adulthood) | In this stage elderly adults revisit the earlier stages and may resolve the stages differently, perhaps less positively, than before. Adults who can come to term with these changes are more likely to have an overall positive perspective on life. |

Figure 4.12. These nine stages of development encompass infancy through elderly adulthood.

These stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances.

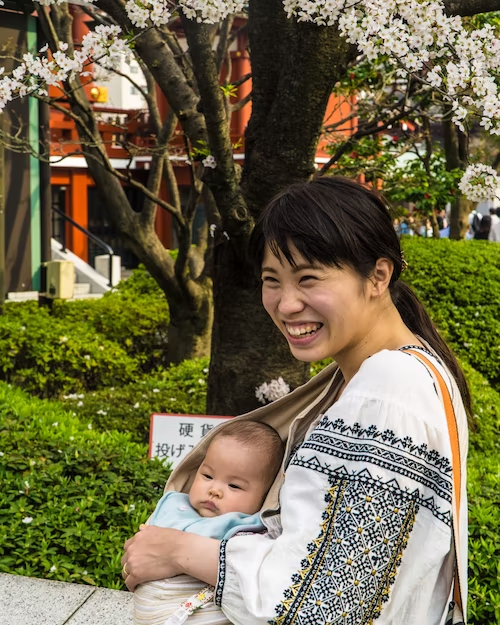

Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development.The theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices. But the overall emphasis on the importance of primary relationships, as shown in Figure 4.13, is universal.

Figure 4.13 The psychosocial theory emphasizes the importance of caregiving, attachment, and parenting as an important part of development.

4.4.2 The Ecological Systems Theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory was introduced in Chapter 3. Here we will explore it more deeply and use it to illustrate the way various systems interact to influence nurturing by parents and other caregivers. This theory helps us look more deeply at the direct and indirect influences on children’s lives without favoring one family form or family circumstance over another.

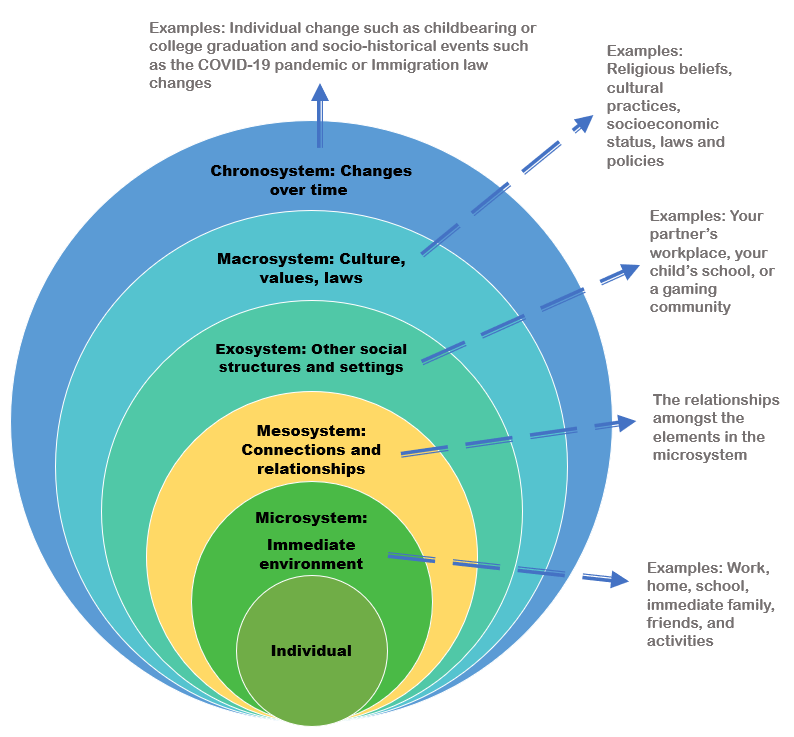

The ecological systems theory was created in the late 1970’s by Urie Bronfenbrenner. He developed this theory to explain how environments affect a child’s or individual’s growth and development. The model in Figure 4.14 shows six concentric circles that represent the individual, environments and interactions:

- Individual: the main concept behind ecological approach, “person in environment” (P.I.E) means that every person lives in an environment that can affect their outcome or circumstance. In helping professions individuals work to improve a person’s environment by helping them identify what is working well and what is negatively impacting them within their environments.

- Microsystem: the smallest system that focuses on the relationship between a person and their direct environment, typically the places and people that the person sees every day often including parents and school for a child or partner, work/school for an adult.

- Exosystem: the people and places that an individual interacts with on a regular basis but not daily, perhaps a place of worship, club, lesson, or social group.

- Mesosystem: the space between the micro and exo systems that represents how those people and places interact and cooperate.

- Macrosystem: the larger values and attitudes of the culture.

- Chronosystem: time as a system that affects individuals.

Figure 4.14. This view of individuals emphasizes the ways that environments, time, and location impact a person’s development.

4.4.3 Nature and Nurture

A well-known debate is nature versus nurture, first coined by psychologist Sir Francis Galton in 1869. With this theory, Galton established the two deciding factors of child development: the biological aspect, known as nature, and the environmental aspect, known as nurture.Because both are important, many experts now refer to nature and nurture rather than as one against the other.

The concept of nature and nurture attempts to explain a child’s development as well as their outcomes through inherited traits and social influences. Nature attributes developed characteristics that are biologically determined, including being inherited from genes. An example of this might include a baby who is born with poor vision, or a chronic condition such as epilepsy. Another example of this might be the biological child of two athletes who is also an exceptional athlete. Or is that an example of nurture? If those two parents provide many opportunities to be active, be coached in sports, and observe athletics, it may be more difficult to separate the effects of nature and nurture. Nurture attributes developed characteristics to socialization. The concept of nurture not only includes academic, artistic, athletic, and social activities, but it also emphasizes the specific type of parenting style implemented.

When discussing the concept of nurture it is important to consider equity. The ability to create varied, stimulating, and rich environments varies from family to family. Socioeconomic status is an important factor that affects all aspects of a child’s environment including what kind of home they live in, the neighborhood structure, which school they attend, and what activities they may participate in. It may also impact the amount of time a parent spends with their child; a parent who works several part-time jobs or relies on public transportation for example, may have less time at home.

The nature and nurture discussion is of great interest to families that include foster and adoptive children. Studies seeking to understand nature and nurture have included biological children who have been raised in different home environments (e.g. adopted into different homes, or one living in a home with the biological parents and others living with adoptive parents.) Other studies compare identical twins (who share the same set of genes) and fraternal twins who may grow up together but are more similar to other siblings in their genetic makeup. The video in Figure 4.15 from FuseSchool-Global Education describes the nature and nurture debate, with a focus on the study of twins, who are often the focus of understanding the effects of nature and nurture.

Figure 4.15. Nature vs Nurture | Genetics | Biology | FuseSchool [YouTube Video]. This video will help you understand the effects of genetics and environment by looking at identical twins.

4.4.4 Baumrind’s Four Styles of Parenting

The categorization of different parenting styles is a perspective on child development credited to Diana Baumrind and expanded by E.E. Maccoby and J.A. Martin. The four parenting styles include: authoritarian, permissive, uninvolved, and authoritative (Figure 4.16).

| Parenting Style | Description | Effects on Development |

|---|---|---|

| Authoritative

“Democratic” |

Parents pay attention to children’s needs and strengths.

Parents set limits and enforce rules. |

Children often become independent, self-reliant, well-liked, and successful in school. |

| Authoritarian “Disciplinarian” | Parents value obedience and punish misconduct.

Parents are less likely to pay attention to children’s pain or difficulties. Parents make decisions unilaterally for children. |

Children may grow up to be aggressive, rebellious and/or with indecisive behavior.

Can contribute to low-self esteem. |

| Permissive

“Indulgent” |

Parents act as a resource without guidance.

Parents allow children to make decisions beyond their developmental level. |

Children may lack self-discipline, have poor social skills, and lack persistence. |

| Uninvolved

“Negligent” |

Parents put little to no effort into caring or raising the child. | Children may experience deficits in many aspects of life, including cognition, attachment, emotional skills, and social skills. |

Figure 4.16. Four Styles of Parenting

Baumrind measured parenting on two dimensions: supportiveness and demandingness. Supportiveness describes characteristics such as paying attention to the unique needs and strengths of each child in order to guide and problem-solve with the child. Demandingness includes having expectations and rules for each child.

Authoritative parenting emphasizes high levels of both supportiveness and demandingness and is considered to produce the most positive outcomes most frequently in the United States.Authoritative parents exhibit interest in their children, pay attention to their unique qualities and experiences, and moderate their demands with this understanding in place.

Authoritarian parenting includes low support combined with a high level of demandingness for their child(ren.) Parents who utilize this type of parenting are known to be strict and controlling and use physical punishment. There have been specific studies that support some authoritarian parenting practices among African American families (Jackson-Newsom et al., 2008). Physical punishment may not be seen as negatively in Asian American or African American culture (Chao, 1994; Nievar & Luster, 2000).

In contrast, permissive parents are high in support yet low in demand. Permissive parents are oftentimes too lenient, or “indulgent,” with their child, which may cause that child to later struggle with authority, self-discipline, persistence, and problem-solving.

The parenting styles theory was modified by Maccoby and Martin with the significant contribution of a fourth parenting style. Uninvolved, or “negligent,” parenting does not provide a child with support or control. The parent, in this case, is inattentive emotionally and/or physically. This may occur in families where parents experience severe health issues or other stressors (Li, 2021).

Parents vary in their style over time and location and will likely fall into one of these styles along a continuum. A parent may be primarily authoritative but exhibit more support than demandingness; or the opposite. In addition, many children have two, three, or more parents in their lifetimes. Each parent will fall on different places of the continuum or perhaps in different styles. It is not simple to correlate parenting styles on child outcomes, but it does help scholars and individuals to understand how parenting plays a role in individual and family outcomes.

4.4.5 Concerted Cultivation and Natural Growth

Sociologist Annette Lareau studied parenting styles of White and Black families that were middle class, working class, and poor during the 1990’s (Lareau, 2002). She identified styles that were based more on class than on race known as concerted cultivation and natural growth.

In Lareau’s findings, middle class families, both white and Black were more likely to identify and foster their child(ren)’s talents, opinions and skills. Concerted cultivation is an approach in which a parent encourages the development of their child’s talents through the controlled and routine engagement in extracurricular activities, like piano lessons, soccer practice, or scouting activities. Families living within the middle-class economic status observe their parents’ involvement questioning and intervening with others. They are also encouraged to think independently, negotiate and to speak up for their own needs. Lareau believes that not only does this prepare children for the dominant culture which privileges active informed citizens, but that it fosters an “emerging sense of entitlement” (Lareau, 2003).

Lower-income families who are poor and/or in the working class prioritize caring for the child and allowing the child to grow naturally in the home or neighborhood. Natural growth is a parenting method that allows for that child’s talents to develop spontaneously, or naturally. Children interact more with siblings as well as multi-aged neighbors. They may develop more skills in leadership, problem-solving, and caretaking because they are organizing their own activities and games, rather than following rules typically designed by adults. They may occasionally engage in structured activities, but these are usually for a limited amount of time. Children observe their parents being helpful and deferential to other adults. At the same time, these parents are often more distrustful of professionals and institutions. Lareau observed that children in the lower class families developed “an emerging sense of constraint.” This sense of constraint may disadvantage children who do not assert themselves in the way the dominant culture and many institutions value.

The neighborhood and home environment , climate change, and increasing reliance on technology both have a significant impact on natural growth. Climate change affects the poor disproportionately; extreme heat, unhealthy air quality, and natural disasters make it more difficult to move easily outdoors. If children live in unsafe or unhealthy areas and cannot get outdoors to play and socialize, they may be more likely to spend time indoors, limited to using electronic devices, and less likely to reap the positive benefits of natural growth.

4.4.6 Attachment Theory

Research demonstrates the importance of connected caregiving on our mate relationships and selection. Largely, this is explained through attachment theory. Attachment theory implies that the capacity to form emotional attachments to others is primarily developed during infancy and early childhood. It is believed that children need to form a healthy attachment with at least one primary caregiver. The psychologists Harry Harlow, John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth each developed aspects of our understanding of attachment and the associated behaviors.

4.4.6.1 Harlow, Bowlby and Ainsworth: Attachment

Psychosocial development occurs as children form relationships, interact with others, and understand and manage their feelings. In social and emotional development, forming healthy attachments is very important and is the major social milestone of infancy (Figure 4.16).Developmental psychologists are interested in how infants reach this milestone. They ask questions such as: How do parent and infant attachment bonds form? How does neglect affect these bonds? What accounts for children’s attachment differences?

Figure 4.17. A child comfortably rests in their parent’s arms.

Researchers Harry Harlow, John Bowlby, and Mary Ainsworth conducted studies designed to answer these questions. In the 1950s, Harlow conducted a series of experiments on monkeys (Figure 4.17). He separated newborn monkeys from their mothers. Each monkey was presented with two surrogate mothers. One surrogate monkey was made out of wire mesh, and she could dispense milk. The other monkey was softer and made from cloth, but did not dispense milk.

The study’s findings showed that the monkeys preferred the soft, cuddly cloth monkey, even though she did not provide any nourishment (Figure 4.18). The baby monkeys spent their time clinging to the cloth monkey and only went to the wire monkey when they needed to be fed. Prior to this study, the medical and scientific communities generally thought that babies become attached to the people who provide their nourishment. However, Harlow (1958) concluded that there was more to the mother-child bond than nourishment. Feelings of comfort and security are the critical components of maternal-infant bonding, which leads to healthy psychosocial development.

Figure 4.18 Harlow’s studies of monkeys were performed before modern ethics guidelines were in place, and today his experiments are widely considered to be unethical and even cruel.

Building on the work of Harlow and others, John Bowlby developed the concept of attachment theory. He defined attachment as the affectional bond or tie that infants form with their mother (Bowlby, 1969). An infant must form this bond with a primary caregiver in order to have normal social and emotional development. In addition, Bowlby proposed that this attachment bond is very powerful and continues throughout life. He used the concept of a secure base to define a healthy attachment between parent and child (Bowlby, 1988). A secure base is a parental presence that gives the child a sense of safety as he explores his surroundings. Bowlby (1969) said that two things are needed for a healthy attachment: the caregiver must be responsive to the child’s physical, social, and emotional needs, and the caregiver and child must engage in mutually enjoyable interactions.

4.4.6.2 Mary Ainsworth’s Research

While Bowlby believed that attachment was an all-or-nothing process, Mary Ainsworth’s research showed otherwise (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). Ainsworth identified the existence of what she calls “attachment behaviors,” which are examples of behaviors demonstrated by insecure children in hopes of establishing or re-establishing an attachment to a presently absent caregiver. As Ainsworth explains, “Since this behavior occurs uniformly in children, it is a compelling argument for the existence of ‘innate’ or instinctive behaviors in human beings” (Psychologist World, 2019).

Ainsworth wanted to know if children differ in the ways they bond, and if so, why. To find the answers to these questions, she used the Strange Situation procedure to study attachment between mothers and their infants in 1970. In the Strange Situation, the mother (or primary caregiver) and the infant (age 12–18 months) are placed in a room together. There are toys in the room, and the caregiver and child spend some time alone in the room. After the child has had time to explore one’s surroundings, a stranger enters the room. The primary caregiver then leaves the baby with the stranger. After a few minutes, the caregiver returns to comfort the child.

Based on how the infants/toddlers responded to the separation and reunion, Ainsworth identified three types of parent-child attachments: secure, avoidant, and resistant (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). A fourth style, known as disorganized attachment, was later described (Main & Solomon, 1990). The most common type of attachment—also considered the healthiest—is called secure attachment (Figure 4.19.).

Figure 4.19. Physical contact contributes to parent-child attachment.

In secure attachment, the toddler prefers their primary caregiver over a stranger. The attachment figure is used by the child as a secure base to explore their environment and is sought out in times of stress. Securely attached children were distressed when their caregivers left the room in the Strange Situation experiment, but when their caregivers returned, the securely attached children were happy to see them. Securely attached children have caregivers who are sensitive and responsive to their needs.

With avoidant attachment (sometimes called insecure or anxious-avoidant), the child is unresponsive to the parent, does not use the parent as a secure base, and does not care if the parent leaves. The toddler reacts to the parent the same way she reacts to a stranger. When the parent does return, the child is slow to show a positive reaction. Ainsworth et al. (1978) theorized that these children were most likely to have a caregiver who was insensitive and inattentive to their needs.

In cases of resistant attachment (also called ambivalent or anxious-ambivalent/resistant), children tend to show clingy behavior, but then reject the attachment figure’s attempts to interact with them (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970). These children do not explore the toys in the room, as they are too fearful. During separation in the Strange Situation, they became extremely disturbed and angry with the parent. When the parent returns, the children are upset and difficult to comfort. Resistant attachment is the result of the caregivers’ inconsistent level of response to their child.

Finally, children with disorganized attachment behave oddly in the Strange Situation. They freeze, run around the room in an erratic manner, or try to run away when the caregiver returns (Main & Solomon, 1990). This type of attachment is seen most often in children who have been abused. Research has shown that abuse disrupts a child’s ability to regulate their emotions.

4.4.6.3 Activity: Strange Situation

Watch this video to view a clip of the Strange Situation.

- Discuss which type(s) of attachment baby Lisa exhibits.

While both Harlow’s and Ainsworth’s research has found support in subsequent studies, they have also met criticism. Some researchers have pointed out that a child’s temperament may have a strong influence on attachment, and others have noted that attachment varies from culture to culture, a factor not accounted for in Ainsworth’s research (Gervai, 2009; Harris, 2009; Van Ijzendoorn & Sagi-Schwartz, 2008). Most notably, research in countries where multiple caregivers are more common has shown that babies can develop secure attachment to more than one caregiver. This finding predicts secure attachments for children who, for example, live in multigenerational homes or have other loving consistent caregivers in home or child care settings.

Importantly, these theories suggest that the attachments we made in early childhood are transferred and displayed in our close relationships throughout life. It is reflected in our belief in ourselves, others, and our social world. While there is evidence to support the correlation of positive attributes such as good self-esteem with secure attachment, it is important to note that poor attachment is not a certain predictor of poor outcomes. Through the understanding of attachment styles and self-reflection exists the power to move beyond damaging dynamics to build healthy and secure relationships.

4.4.6.4 Attachment: Cultural Considerations

Without diminishing the significance of Ainsworth, Bowlby, and Harlow’s findings, it is important to consider cultural differences when examining attachment. Both of these studies were completed in Western societies where individualism is the dominant culture; thus many participants shared common cultural ideals relating to child-raising. Individualist cultures typically place greater emphasis on the independence, individualism, and self-sufficiency of the child, and typically children will be largely raised by a few trusted adults.

Collectivist cultures, however, tend to place more emphasis on mutual effort and interdependence, and tend to include a more community-based method of raising children, including roles for extended family and community networks. Additionally, many young children are taught to help care for infants as primary caregivers, which is not commonplace in many Western cultures. Parenting styles can also have varying effects in different cultures, and while one style of parenting may work well in one culture, it may not be as effective in another.

Levels of emotional expression also vary across different cultures. For example, in sub-Saharan farming communities, emotional expression is seen as disturbing, therefore children are socialized early in life to maintain neutral expressions. Additionally, while stranger anxiety was treated as a universal norm in The Strange Situation Experiment, it has been found that children in these farming communities do not show a predisposition to stranger anxiety. In fact a study conducted by Hiltrud Otto in 2004 found that the majority of infants in Cameroonian Nso farming communities were not afraid of strangers picking them up or moving them away from their mothers. Instead they were found to display neutral facial expressions and experienced decreased levels of the stress hormone cortisol as the stranger approached (Keller, 2018).

These examples are not representative of all cultures, nor do they encompass all variations regarding how children are raised or form attachments. The range of variance in cultural norms can differ based upon many factors including but not limited to environmental interactions and sociocultural history. It is also important to note that these differences do not only occur in other countries. In addition to the dominant culture within the United States, there are also many subcultures, or groups within our society whose beliefs and interests differ from the dominant culture. These subcultures originate in part from our multicultural history, and may look either very similar to the dominant culture, or they may look largely dissimilar (Keller, 2018). Regardless of perceivable differences it is important to be able to view cultures as valid in their own right by practicing the evaluation of a culture by its own standards, and not through the standards of another culture; as such, the avoidance of ethnocentrism fosters an environment of understanding, as it does not attempt to force either culture to adapt or change for the other, but instead allows for understanding of validity for both.

As we move forward, it will be important to consider how we conduct studies, including the inclusion of an emphasis on family structures in addition to cultures. Currently much of the research being conducted on families focuses mainly on maternal figures, and does not focus as heavily on paternal figures or caregivers.

4.4.7 Licenses and Attributions for Child and Family Theories and Perspectives

4.4.7.1 Open Content, Original

“Nature and Nurture”, Baumrind’s Four Styles of Parenting” and “Concerted Cultivation and Natural Growth” by Shyanti Franco and Elizabeth B.Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.16. “Four Styles of Parenting” chart by Shyanti Franco is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Activity: Strange Situation” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Attachment: Cultural Considerations” by Genna Watkins is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

4.4.7.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

“Psychosocial Theory” is an adaptation of Erik Erikson’s PsychoSocial Theory from Child Growth and Development by College of the Canyons, used under a CC BY license.

Figure 4.12 is an adaptation of Erik Erikson’s PsychoSocial Theory from Child Growth and Development by College of the Canyons, used under a CC BY license. Adaptation: addition of “Revistation of Previous Stages” to table.

Figure 4.13 “Individual Protection” by Martin Gommel is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Ecological Systems Theory” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Introduction to Human Services is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.14. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Visualization by Elizabeth B. Pearce/ Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Attachment Theory” is an adaptation of “Childhood” by Lumen Learning, and “1950’s: Harlow, Bowlby, and Ainsworth” in Parenting and Family Diversity Issues by Lumen Learning and Diana Lang, used under a CC BY 4.0 license. Adaptations: merging of content and images, new images, and edited for equity and brevity.

Figure 4.17. Photo on pxhere.com is licensed under CCO Public Domain.

Figure 4.19. Photo by Guille Álvarez on Unsplash is licensed under the Unsplash License.

4.4.7.3 All Rights Reserved

Figure 4.15 Nature vs. Nurture by Nature School is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 4.18 Harlow’s Studies on Dependency in Monkeys on Michael Baker’s channel is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

4.4.8 References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41(1), 49-67. ↵

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development,41(1), 49-67. ↵

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41(1), 49-67. ↵

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum. ↵

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books. ↵

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books. ↵Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13(1), 673-685. ↵

Gervai, J. (2009). Environmental and genetic influences on early attachment. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-25 ↵

Harris, J. R. (2009). Attachment theory underestimates the child. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X09000119 ↵

Keller, H. (2018). Universality claim of attachment theory: Children’s socioemotional development across cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(45), 11414-11419. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720325115

Lareau, Annette. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 121-160). University of Chicago Press. ↵

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 121-160). University of Chicago Press. ↵

Psychologist World. (2019). Attachment theory. https://www.psychologistworld.com/developmental/attachment-theory ↵

Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2008). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: Universal and contextual dimensions. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 880–905). Guilford Press. ↵