3.2 Introduction to Connection, Love, and Community

Elizabeth B. Pearce, Wesley Sharp, and Nyssa Cronin

“A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

– Albert Einstein, in a letter he wrote to a rabbi whose family was grieving over the loss of his child (Sullivan, 1972).

The need for, and benefits of, being connected in an emotional and social way to other human beings is one of the central foundations of family life. The quote speaks to the tension among Western, Eastern, and Indigenous views about individuality and collectivism. Einstein refers to the “optical delusion” (what we might call a social construction) of seeing ourselves as separate beings from others and the natural world. Increasing layers of research, however, speak to the importance of close social relationships (belongingness and connectedness) as well as the wider circle of social networks (Seppala et al., 2013).

Theorists who discuss families, parenting, and mate selection rely on an underlying principle: the mutual social and emotional interdependence of human beings that fosters family development and growth. In addition, our ability to connect to the greater society and planet, including those who are less similar or unrelated to us, enhances our care for family and community. An emphasis of this text is the disposition of being willing to listen and to learn about the greater community in which we live.

As we discuss social connection, we are referring to qualities and experiences such as:

- Positive relationships with others in the social world;

- Attachment, an affectionate emotional connection with at least one other;

- A feeling of belonging and lack of feeling of exclusion;

- Social support, which includes connection but may also include informational support, appraisal support (such as personal feedback and/or affirmation), and/or practical support (such as money or labor);

- The act of nurturing and being nurtured;

- An individual’s perception of all of the above.

It matters most to the individual what they perceive as connection and support, and less how others would view it.

3.2.1 Theoretical Perspectives that Emphasize Connection

In this section, we’ll discuss the ecological systems theory and the hierarchy of needs theory, two theories that emphasize the importance of our connections with others. It is believed that systems of support are critical to individual and family well-being.

3.2.1.1 Ecological Systems Theory

The ecological systems theory was developed by psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner to explain how environments affect a child’s or individual’s growth and development. The model is typically illustrated with six concentric circles that represent the individual, environments and interactions (see Chapter 4, Figure 4.14). Bronfenbrenner’s model shows the individual at the center of concentric circles that represent all the people and places in that person’s life. The outer circles include the community values and norms, as well as the person’s location in time and geography. Although Bronfenbrenner identified systems which will be explored in depth in Chapter 4, it can be argued that all systems consist of people. It is the people within these circles that will interact with and impact each of us.

3.2.1.2 Hierarchy of Needs Theories

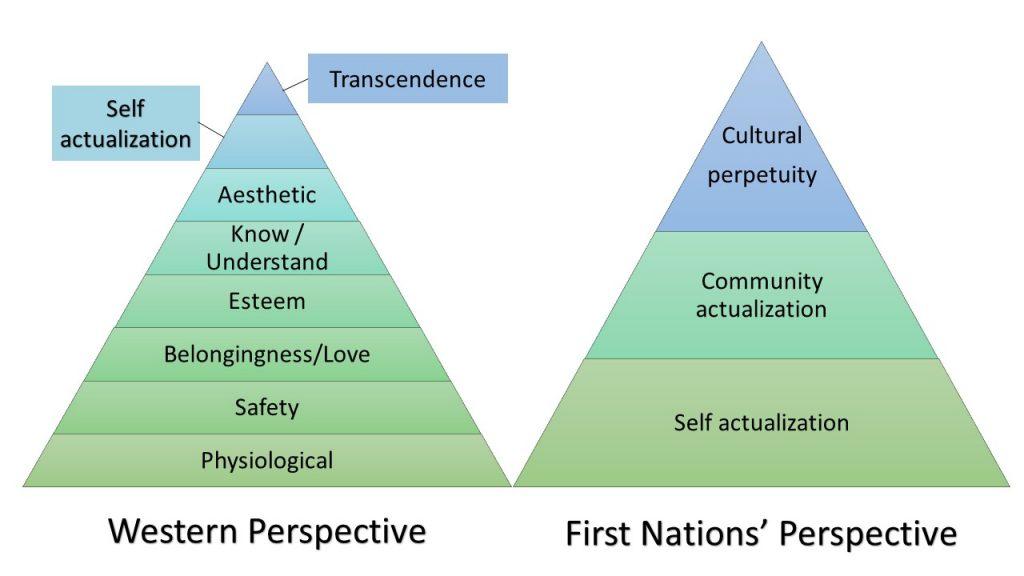

There are hierarchy of needs theories created by multiple Indigenous groups, and best documented by the Blackfoot Nation in North America, that emphasize the self-actualization of not just the individual, but of the community as the most primary of needs (Figure 3.1 right.) Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, described in Chapter 2, includes the emotional need for affection and loving connections to others once basic physiological and biological needs are met (Figure 3.1, left.)

Figure 3.1. Comparison between Maslow’s Hierarchy and First Nations Perspective.

In 1938 Maslow spent time with the Blackfoot Nation (link to archival photo) in Canada prior to releasing his hierarchy of needs theory. It is believed that he based the teepee-like structure on the Blackfoot ideas but westernized the focus to be on the individual rather than on the community (Bray, 2019).

If we look more closely at the representation of Blackfoot ideas, it can be seen that the well-being of the individual, the family, and the community are based on connectedness, the closeness that we experience with family and friends, and the prosocial extension that we provide to others in our communities and in the world. In addition, this model focuses on time; the top of the teepee is cultural perpetuity and it symbolizes a community’s culture lasting forever.

Maslow’s theory is of value, but the mislabeling of it as a theory of human development rather than as a Western cultural theory of human development mistakenly applies what Maslow observed to all human beings. Bringing theories from other cultures and geographical regions forward helps us to understand the variety of ways that human beings develop and to recognize the value of the diversity of family experiences and beliefs.

3.2.2 Social Support Networks

Human connectedness and prosocial relationships are increasingly associated with better health outcomes and longevity. The World Health Organization now lists “Social Support Networks” as a determinant of health. Their webpage notes that a person’s social environment, including culture and community beliefs, is a key determinant in overall health (World Health Organization, 2020).

This country has a history of immigration law that has often separated families, including spouses. As introduced in Chapter 2, this practice contributes to the number of transnational families, many of whom are involuntarily so. In 2018, the United States developed a “zero tolerance” policy toward illegal immigration from the South and imprisoned families seeking legal status, separating children from parents. Although the policy officially ended in June 2018, it continued, with at least 1,100 additional children being separated from their parents since that time.

Public health officials are working to move forward the prioritization of social connections as a part of public health efforts in the United States. They propose examining current evidence and research, conducting additional research, and creating a consensus process amongst experts related to social connectedness (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017).

It seems that once we feel connected to others that a more familial sense of belongingness can develop, which then benefits individuals and the greater community. This research supports the belief systems of indigenous peoples, such as the Blackfoot Nation discussed earlier, and Eastern philosophies which see a reciprocal relationship between the good of the community, the planet, and the good of individuals.

In this chapter, we will explore kinship connections, including chosen families and partner or mate selection. In addition, we will look more closely at the factors that affect our partner choices and family formations, including psychological, societal, and institutional factors.

3.2.2.1 Kinship and Extended Kinship

Kinship, as discussed in Chapter 1, refers to the broader social structure that ties people together (whether by blood, marriage, legal processes, or other agreements) and includes family relationships. Kinship acknowledges that individuals have a role in defining who is a member of their own family and how familial relationships extend across both vertical and horizontal lines. For example, in families with multiple living generations, there is the possibility of close relationships between young children, grandparents, and great-grandparents. Families who have large sibling groups can have family reunions that include dozens or even hundreds of people. These relationships are called extended kinship or extended families and can also include non-blood or legal relatives as designated by the kinship group.

We will use the terms “kinships” or “kinship groups” interchangeably with “families” to remind ourselves of this broader definition (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Connection to other people is a foundational need that can be met through extended kinship groups.

3.2.2.2 Chosen Families

According to The SAGE Encyclopedia of Marriage, Family, and Couples Counseling, “chosen families are nonbiological kinship bonds, whether legally recognized or not, deliberately chosen for the purpose of mutual support and love” (Carlson & Dermer, 2019). Chosen family is an option for every individual, although it has historically been associated with the LGBTQ+ culture. People who identify as lesbian, gay, or other stigmatized identities have sometimes been disowned by families who do not accept these identities and therefore do not accept their children (or other family members).

Chosen families can be for anyone of any background who desires to connect through kinship bonds with others who are not blood- or legally-related individuals. The chosen family can meet or supplement needs not sufficiently met by the biological or otherwise traditionally structured family. In some cases, people are ostracized from their family of origin and are denied a sense of belonging. Others may be living away from their biological families due to schooling, immigration, employment, legal restrictions, migration, or other reasons.

In addition, both chosen families and extended kinship relationships may be created through hardship. As described in Chapter 1, Black people who were enslaved found ways to create kinship ties among the hostile living conditions that separated them from biological and legal family members. Native Americans and immigrant groups facing oppressive laws and policies continued to foster familial and kinship connections within communities. Chosen families are created for a variety of reasons, and it is important to see them through the lenses of love, connection, nurturance, and equity.

In this chapter, we will focus on the romantic, sexual, and partnership unions that people make by starting with an overview of sex, gender, and sexuality. The following chapter, Nurturance, will focus more on parenting and other caregiving aspects of family life.

3.2.3 Licenses and Attributions for Introduction to Connection, Love, and Community

3.2.3.1 Open Content, Original

“Introduction to Connection, Love, and Community” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Wesley Sharp, and Nyssa Cronin is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.1. “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs compared to the First Nations’ perspective” by the Contemporary Families team is licensed under: CC BY 4.0. Based on research from Rethinking Learning by Barbara Bray.

3.2.3.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 3.2. Photo by Priscilla Du Preez. License: Unsplash license.

3.2.4 References

Seppala, E., Rossomando, T., & Doty, J.R. (2013). Social Connection and Compassion: Important Predictors of Health and Well-Being. Social Research: An International Quarterly 80(2), 411-430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/sor.2013.0027

Bray, B. (2019, March 10). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot Nation beliefs. Retrieved December 28, 2019, from https://barbarabray.net/2019/03/10/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-and-blackfoot-nation-beliefs/

World Health Organization. (2020). The social determinants of health. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Trump administration family separation policy. (2020). Wikipedia. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trump_administration_family_separation_policy

Holt-Lunstad, J., Robles, T. F., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000103

Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S. L., Lewis, B. P., Luce, C., & Neuberg, S. L. (1997). Reinterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(3), 481–494

Carlson, J., & Dermer, S. B. (Eds.). (2019). The SAGE encyclopedia of marriage, family, and couples counseling. SAGE Reference.

Sullivan, W. (1972, March 29). The Einstein Papers. A man of many parts. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1972/03/29/archives/the-einstein-papers-a-man-of-many-parts-the-einstein-papers-man-of.html