5.4 Culture

As discussed in Chapter 2, culture, broadly defined, is the set of beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society. Culture elements are learned behaviors; children learn them while growing up in a particular culture as older members teach them how to live. As such, culture is passed down from one generation to the next.

Culture and ethnicity are deeply intertwined. Ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national, ancestral, or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; with relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and with some sense of identity or belonging to the subgroup. Pan-ethnicity is the grouping together of multiple ethnicities and nationalities under a single label. For example, people in the United States with Vietnamese, Cambodian, Japanese, and Korean backgrounds could be grouped together under the pan-ethnic label Asian American. The United States has five pan-ethnic groups, including Native Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, European Americans, and Latinos. The grouping together of multiple ethnicities or nationalities under one umbrella term can be very problematic.

Sometimes ethnicity and race are used to categorize groups of people, which can be a source of confusion. The ways that people think of themselves could vary from how the U.S. government defines race and ethnicity. For example, an individual could identify as Latinx, but when completing administrative forms, such as a the U.S. census, the person would not have “Latinx” as an option, and instead need to select one of the categories “Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano;” “Puerto Rican,” “Cuban,” or “Another Hispanic, Latino, Spanish origin.” To add yet another layer of potential confusion, sometimes nationalities and ethnicities are used interchangeably. The U.S. census has been used to categorize people by race and ethnicity, and the category names can change as a reflection of shifts in public attitudes and politics, and demographic changes. The first U.S. census was conducted in 1790, and is completed every ten years. The 2020 census categories for race & ethnicity included the following :

- White+*

- Black or African American+*

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Chinese

- Japanese

- Filipino

- Korean

- Asian Indian

- Vietnamese

- Other Asian

- Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Native Hawaiian

- Samoan

- Chamorro

- Other Pacific Islander

- Some other race

- Hispanic

- Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano+*

- Puerto Rican

- Cuban

- Another Hispanic, Latino, Spanish origin

[footnote: The “+” symbol indicates in the 2020 census, if a person checked that option, they could for the first time write more about their origins, such as “Irish” or “Lebanese” if they selected “White,” or “Jamaican” or “Somali” if they selected “Black or African American.”]

In addition to culture and ethnicity, other terms are used to refer to this aspect of cultures, such as majority and minoritized or marginalized cultures, or dominant and nondominant cultures or macro- and micro-cultures. Some groups within a larger culture relate to the social identities of those involved. These may be based on regions (the old South, the East Coast, urban, rural), religion or beliefs: (Catholics, Southern Baptists, Lutherans, Buddhists, Muslims, atheists), or affiliation (street gangs, NASCAR fans, college students). Such groups are not necessarily distinct cultures, but groups of people who share concerns and who might perceive similarities due to common interests or characteristics (Lustig & Koester, 2010).

The way culture operates in families is that, as previously discussed, families maintain traditions, rituals, and routines, which are heavily influenced by the cultural space(s) that families occupy. The section X will discuss ways in which culture operates in family functioning, and the complexities for families that occupy more than one cultural space.

5.4.1 Cultural Erasure versus Persistence

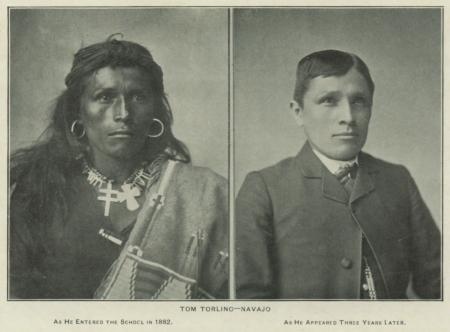

Cultural erasure is the practice of a dominant culture contributing to the erasure of a non-dominant or minoritized culture. An example of active cultural erasure would be that of Native American children being forced to attend residential boarding schools, where they might be punished for speaking their heritage language, would wear uniforms that were stripped of makers of their their community and identity, and harshly mistreated, even to the point of starvation or being beaten (Figure 5.10). The strategy of not allowing the children to speak their communities’ languages, or learn and practice their communities’ traditions and rituals, was active cultural erasure. Passive cultural erasure could include the histories of communities not being included in historical textbooks, or the passing of laws that prohibit people from wearing jewelry, hair styles, clothing, or other items that are indicators of one’s cultural identity.

Figure 5.10. The photographs here show “before” and “after” portraits of a student at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a residential boarding school built on the idea that education should “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Cultural persistence, then, is the very opposite of cultural erasure. Cultural persistence is when elements of culture, such as language, rituals, foodways, traditions,persist despite efforts to blot out those cultural practices and identities. An example of cultural persistence is that of language revitalization programs among Native communities, such as the Chinuk Wawa language program, supported by Lane Community College (LCC) in Eugene, Oregon. This program consists of a collaboration between Lane Community College, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, and the Northwest Indian Language Institute of the University of Oregon (UO). Through this program that has operated for nearly a decade, provides language classes for tribal members, LCC and UO students, as well as community members on the Grand Ronde Reservation.

5.4.2 The Overlap of Culture and Religion

As previously discussed, culture is composed of beliefs, values, symbols, rituals, and various other elements, particularly that of religion. Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions, and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to explain the origin of life or the universe.

If you would like to explore the topic of how culture and religion overlap in human lives, we recommend the TED Talk by the anthropologist Wade Davis, “The worldwide web of belief and ritual.” Davis provides many examples of the deep familiarity and knowledge indigenous communities develop and pass on to the next generations. Using the example of the Elder Brothers, a group of Sierra Nevada Native Americans, Davis discusses how rituals practiced by groups are deeply intertwined with their cosmologies.

5.4.3 Licenses and Attributions for Culture

5.4.3.1 Open Content, Original

“Culture” and all subsections, except those noted below, by Monica Olvera are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

5.4.3.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

“Culture” by Libre Texts is licensed under CC BY-SA.

“Ethnicity and Religion” by Libre Texts is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

“Culture” by Knudsen, K. G., Ruth Fairchild, Bev, & Lease-Gubrud, D. is licensed under CC BY-NC.

“The Nature of Religion” by Libre Texts is licensed under CC BY-SA.

“The worldwide web of belief and ritual” by Wade Davis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND.

“Family Connectedness and Identity” by Libre Texts is licensed under CC BY-SA.

“Tom Torling – Navajo” by Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center is licensed under CC BY-NC.

5.4.4 References

Davis, W. (2008). The worldwide web of belief and ritual. TED.

Lustig, M., & Koester, J. (2010). Intercultural communication: interpersonal communication across cultures. J. Koester.–Boston: Pearson Education.

What Census Calls Us. (2020, May 30). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/interactives/what-census-calls-us/