8.2 Housing and Homes

Elizabeth B. Pearce, Katherine Hemlock, and Carla Medel

“I just feel like I influence people because I’m like—I was practically homeless.” — Cardi B

Housing is another word for the place that families go each night to find shelter not only from the physical elements, but also to find enough emotional safety that they can become centered, rejuvenated, and sleep securely. In the best scenarios it provides not only security, but a place for families to love and nurture the self and one another.

Figure 8.1. Cardi B rose from poverty to fame.

Cardi B, a famous rapper (born as Belcalis Almanzar), describes being able to move out of her abusive boyfriend’s home with money earned from her work stripping in a club. “There were two pit bulls in that house, and I had asthma. There were bed bugs, too,” she told Vibe. “On top of that, I felt like my ex-boyfriend was cheating on me, but it was like even if he was cheating on me, I still can’t leave because—where was I gonna go?” (Akhtar, 2017).

In Cardi B’s (Figure 8.1) case, she had safety from the outside physical world. But she was not safe inside her home. This is just one example of the complexities of housing, and specifically the ways that inequities play out in the United States.

Income is the primary determining factor in housing access. Price, availability, location, and macroeconomics all play a role, but a family’s annual income is the main determinant in housing affordability (Tilly, 2006). Therefore, inequities in income distribution directly affect housing access, and the capability of families to be safe, secure, and able to function to their maximum potential.

Cardi B grew up living between two different Bronx neighborhoods in New York City. When she describes her parents, she says, “I have real good parents, they poor. They have regular, poor jobs and what not,” she said in an interview with Global Grind. “They real good people and what not, I was just raised in a bad society” (Shamsian & Singh, 2019). It is common for U.S. families to have multiple wage-earners, with multiple jobs, and still be unable to afford adequate housing.

Figure 8.2. It is common in the U.S. for families to have multiple wage-earners, with multiple jobs, and still be unable to afford adequate housing.

Part-time and temporary jobs frequently come with lower pay and fewer benefits such as health care, sick leave, and other paid and unpaid leaves. This makes it harder to budget for regular expenses such as food and housing. Sex, sexuality, immigration status, and ethnicity matters when it comes to full-time permanent work, meaning that it is also likely women, immigrants, and people from marginalized ethnic and sexuality groups are more likely to have fewer of these jobs and more difficulty saving for housing.

Affordable housing is defined as housing that can be accessed and maintained while paying for and meeting other basic needs such as food, transportation, access to work and school, clothing, and health care. Diverse income levels, reinforced by governmental and lending practices that discriminate based on racial-ethnic groups, immigration status, and socioeconomic status, widen the gap between those who are housing secure, housing insecure, and homeless.

8.2.1 Houselessness

In 2019, over a half million Americans were considered houseless which means they do not have a permanent place to live. Commonly referred to as “the homeless” or “homeless people” in the past, the terms “unhoused” and “houseless people” are now considered to be more respectful and accurate. This encompasses the movement toward “person-first language” as well as the distinctions between a house, which refers to a physical shelter, and a home, that includes both shelter as well as family, loved ones, or other comforts.

Many of the people lacking housing are children and youth. In early 2018, just over 180,000 people in 56,000 families with children experienced houselessness. More than 36,000 young people (under the age of 25) were unaccompanied youth who were houseless on their own; most of those (89 percent) were between the ages of 18–24 years (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2018). In 2020 580, 466 people were experiencing houselessness (Figure 8.3).

8.2.1.1 On a single night in 2020, 580,466 people in the U.S. were experiencing houselessness.

Figure 8.3. In the 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to the U.S. Congress reported about persons who experience homelessness during a 12-month period, point-in-time counts of people experiencing homelessness on one day in January, and data about shelter and housing available in a community.

Figure 8.3. In the 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to the U.S. Congress reported about persons who experience homelessness during a 12-month period, point-in-time counts of people experiencing homelessness on one day in January, and data about shelter and housing available in a community.

The AFAR reports on demographics such as age, veteran status, families with children, and whether people are in sheltered or unsheltered locations while houseless.

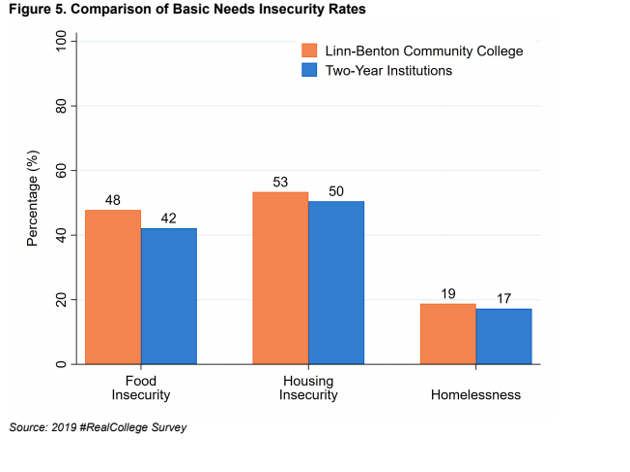

As shown in Figure 8.4, a recent national survey that included Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC) in Albany, Oregon found that students at the two-year institution had higher levels of houselessness than do their counterparts nationally. With a response rate of 9.7 percent, 558 of 5,700 surveyed LBCC students participated in the 2019 #RealCollege Survey Report instituted by Temple University in 2019. Nineteen percent of LBCC students reported experiencing houselessness in the past year, compared with 17 percent nationally. In addition, 53 percent of LBCC students reported experiencing housing insecurity (described below) in the past year, compared with 50 percent nationally.

Figure 8.4. A recent national survey that included Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC) in Albany, Oregon found that students at the two-year institution had higher levels of houselessness than do their counterparts nationally.

This report indicates that more than half of community college students are struggling with some kind of stress related to having a safe, stable place to care for themselves and their families. Demographic factors that indicate a higher rate of houselessness and housing insecurity include being a woman, being transgender, being Native American, Black, Latinx,or 21 or older. Although White people, men of color, younger students (18-20), and athletes were less likely to experience houselessness or housing insecurity, they still did so in double-digit percentages (Goldrick-Rab et al., 2019).

Living in tents, couch surfing and car sleeping all are forms of houselessness. In an effort to provide stability and safety to the houseless population, formal encampments called tent cities have popped up across America in response to the cost of living and other societal problems (Figure 8.5). Dignity Village in Portland, Oregon, provides a community that is self-organized and offers a bit of security. Because the majority of tent cities are not legal, people living in them lack stability and live under the threat of being swept or evicted. In 2017, there were 255 tent cities reported across the United States, ranging in size from 10 to over 100 people living in them. “Of those [tent cities] where legality was reported, 75 percent were illegal, 20 percent silently sanctioned, and 4 percent legal.” Tent cities are a response to the fact that most city-run shelter beds are maxed out and affordable housing has not become available in response to the growing need (Invisible People, n.d.).

Figure 8.5. The Wayne Morse Federal Courthouse is within sight of a temporary location of the Whoville Homeless Camp in Eugene, Oregon.

8.2.2 Shelters for People Experiencing Houselessness (aka Homeless Shelters)

Shelters for people who are houseless provide needed temporary immediate service to over 1.5 million Americans each year (Popov, 2017). Primarily federally funded, many nonprofit organizations also provide support and temporary shelter for families and individuals. Some are so full that they sleep people in shifts, especially in the cold of winter. Many houseless people have nowhere to go during the day; however, day shelters such as Rose Haven in Portland, Oregon, offer services to those in need. The shelter serves about 3,500 individuals, including women, children, and gender non-conforming people who experience trauma, poverty, and health challenges.

Tensions exist among tent dwellers, staff, and users of shelters, and the business and home-owning communities. This is exemplified in Corvallis, Oregon, where the community has struggled for years to find a permanent location for the men’s overnight cold-weather shelter. Advocates for people who are houseless argue for a location close to needed city services; accessibility is important when walking, bicycling, and public transportation are the primary modes of getting around. These needs bump up against business owners’ desires for welcoming environments. Most recently, churches outside of the downtown area have allowed people to erect tents on the church property (Hall, 2019). With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, more people who are houseless are moving into tents, and the city has intentionally stopped removing illegal campsites. In addition, Corvallis is providing hygiene centers that include showers, hand-washing, laundry, and food services (Day, 2020).

The socially constructed ideas of “normal” or “acceptable” identities are barriers to many people in accessing shelter, housing, and other services. In houseless shelters, transgender women may be refused admittance by the women’s shelter and at risk of violence at the men’s shelter. More progress must be made to provide security for all, regardless of identity (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2019).

Another barrier some women with children face in seeking shelter from domestic violence is the shelter rules themselves. Early curfews and overly strict rules can compromise the empowerment of residents. Many women fleeing domestic violence find themselves facing punitive and inflexible environments that mimic the patterns of control they are trying to escape. The Washington State coalition against domestic violence, called Building Dignity, “explores design strategies for domestic violence emergency housing. Thoughtful design dignifies survivors by meeting their needs for self-determination, security and connection. The idea here is to reflect a commitment to creating welcoming accessible environments that help to empower survivors and their children” (Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, n.d.).

8.2.3 Housing Insecurity

Housing insecurity is less obvious than houselessness. People who are houseless are somewhat visible, but we may be less likely to know whether or not someone is housing insecure. That’s because it is an umbrella term that encompasses many characteristics and conditions. Signs of housing insecurity include missing a rent or utility payment, having a place to live but not having certainty about meeting basic needs, experiencing formal or informal evictions, foreclosures, couch surfing, and frequent moves (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, n.d.). It can also include being exposed to health and safety risks such as mold, vermin, lead, overcrowding, and personal safety fears such as abuse (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). Cardi B’s living situation, which she describes as “practically homeless,” illustrates housing insecurity.

Housing insecurity can be defined as a social problem; the current estimates are that 10–15 percent of all Americans are housing insecure. The increase in the number of cost-burdened households, households that pay 30 percent or more of monthly income toward housing, is dramatic among families who rent homes. Since 2008, these households increased by 3.6 billion to include 21.3 billion by 2014. And households with the most severe cost burden (paying 50 percent or more for housing) increased to a record 11.4 million (Harvard University, 2016). By definition, a cost-burdened household is one that also faces housing instability and insecurity.

8.2.4 Somewhere In-Between

A well-established housing system that is often overlooked is immigrant housing. There are many immigrants who come to the United States as part of a guestworker program, which dates back to 1942 with the Bracero Program and continues through the hiring today of H2-A workers. Although these folks are called “guest workers,” they are not treated as guests when it comes to living spaces.

The Bracero Program was an agreement between the United States and Mexico to bring in a few hundred Mexican laborers to harvest sugar beets in California. What was thought to be a small program eventually drew at its peak more than 400,000 workers a year. When it was abolished in 1964, a total of about 4.5 million jobs had been filled by Mexican citizens. After the Bracero Program, foreign workers could still be imported for agricultural work under the H-2 program, which was created in 1943 when the Florida sugar cane industry obtained permission to hire Caribbean workers to cut sugar cane on temporary visas. The H-2 program was revised in 1986 and was divided into the H-2A agricultural program and the H-2B non-agricultural program which are still up and running today. These programs provide temporary jobs and income for workers but do not offer any advantage in terms of establishing residency or citizenship in the United States.

The protections provided to these guest workers vary depending on the program they are under, so the quality of living varies widely but is often low quality. The housing vicinities lack basic necessities and are often in areas considered to be dangerous. Many guest workers find themselves living in one-room containers that later may be split up between many workers. Other guest workers find themselves living in tent cities, placed right next to the field where they are picking crops. One tent is provided to fit multiple guest workers or an entire family.

These living spaces are often in very rural locations, which isolate these workers and make them totally reliant on their employers. Many employers forbid them from bringing visitors, which reinforces the guest workers’ dependence on the employer and limits the likelihood of reports about the poor living conditions or other violations (Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d.).

8.2.5 Licenses and Attributions for Housing and Homes

8.2.5.1 Open Content, Original

“Housing and Homes” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Katherine Hemlock, and Carla Medel is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.3 by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi-Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

8.2.5.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.1. “Cardi B live auf dem Openair Frauenfeld 2019″ by Frank Schwichtenberg.License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 8.2. “home sweet home” by Libor Gabrhel. License: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.4. “Whoville Homeless Camp (Eugene, Oregon)” by Visitor7. License: CC BY-SA 3.0.

8.2.5.3 All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.5. “Comparison of Basic Needs Insecurity Rates” (c) The Hope Center. Used with permission.

8.2.6 References

(currently listed in section 8.3)