Industrialization and the Factory

After the Civil War, the United States economy passed into an era of rapid industrialization. The term industrialization is used here to describe a process of development that reorganizes productive activities such that they conform to a machine logic, as opposed to a handicraft logic. That is, the economy becomes increasingly constituted by a series of interconnected machine processes. When we think of the United States undergoing industrialization we are really envisioning its economy becoming a large-scale machine, capable of churning out all of the goods required to sustain the community efficiently and to sustain the machine itself, through production of intermediate goods. When we think of the economy as industrializing we are actually considering a qualitative change in the economic system. To better understand what a qualitative change in the economic system entails, consider the following key features of an industrialized, machine process economy.

Large-scale technologies that make up the core of the economic system.

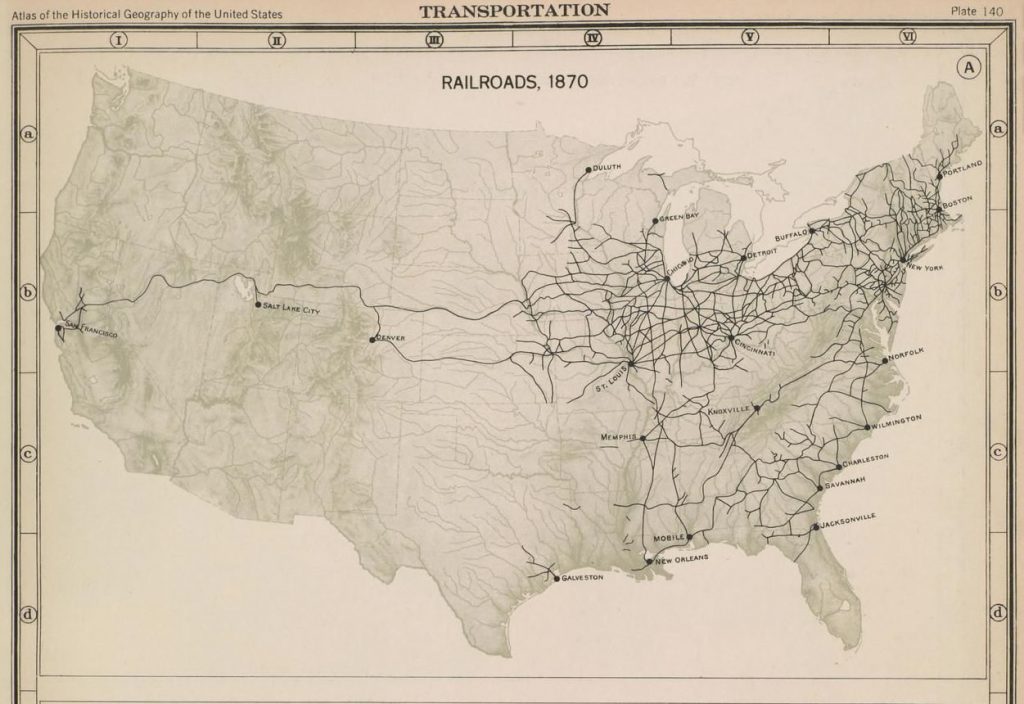

Particular combinations of technology incorporated into the economic system were massive in scale. For example, consider again the case of the railroads. We have previously discussed why railroads required administration from the managerial bodies of corporate entities capable of organizing the business over the scale and scope of its activities. The technology itself was massive – establishment of steam powered with a rail and car transportation system over vast geographical areas was quite literally the greatest engineering marvel that humans had achieved to date. With the railroads came the telegraph, which created the possibility for transnational and interregional rapid communication. Other hallmark technologies of an industrializing 19th century American economy include: electric light and power, streetcars, improvements in steel production, and petroleum refining.

Figure 7. Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Plate 140 by Charles O. Paullin. Curated by the Carnegie Institution of Science

Integrated chains of production that link markets and industries.

The largeness of the business enterprise implies a high degree of interconnectedness between different stages in the production of the social product. To illustrate our point, consider the generation and provisioning of electric power. We can envision a simplified model of electric generation by breaking the whole production process into four stages:

- Production of fuel source. In this example, we will assume we’re talking about a coal fired power plant. This is a good choice, because coal served as the primary fuel source for electric generating during its advent in the United States. Coal is produced by mining and is subject to geological processes that have resulted in an uneven spatial allocation of coal in the earth’s crust. Therefore, coal can only be mined in certain areas. The story of coal in America begins in Pennsylvania.

- Energy conversion. The chemical energy embodied in coal must be converted into mechanical energy before it may be used to generate electricity. This conversion process is accomplished by burning the coal to transform water into steam, which creates the necessary pressure to power an engine. The engine now embodies some of the energy that existed in the coal, less losses due to inefficiencies in the conversion process. The steam engine itself is the product of a set of interconnected production processes.

- Electric Generation. The mechanical energy of the steam engine is then used to power an electric generator. Electric generators require steel, copper, and most importantly, a patent to produce.

- Distribution. Once generated, the electricity is distributed to the end user via cables that conduct electricity. Edison’s first system in New York used copper as its conductor.

If you think about each of these stages of production occurring as a production process that occupies a different space geographically, then you begin to see how something like the provisioning of electricity is really a network of interdependent production processes that establishes connections between different regions. Coal is mined in Pennsylvania, and then shipped to New York for use as fuel in the production of steam. A boiler and steam-powered electric generator is purchased from a firm in New York that is licensed to sell Edison patented systems. Edison’s generators are produced in upstate New York and require a steady flow of steel from Pennsylvania and copper from Michigan for ongoing production. And so on. Every single economic activity is the product of an orchestra of interconnected production processes. To function efficiently those interdependencies must be managed so that they they function as a whole machine. This is what we mean when we describe the economy as industrialized.