2.2 – What is Orthodox Economics?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of studying orthodox economics

- Explain the relationship between production and division of labor

- Evaluate the significance of scarcity in orthodox economics

Orthodox (or Neoclassical) Economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity. These can be individual decisions, family decisions, business decisions or societal decisions. If you look around carefully, you will see that scarcity is a fact of life. Scarcity means that human wants for goods, services and resources exceed what is available. Resources, such as labor, tools, land, and raw materials are necessary to produce the goods and services we want but they exist in limited supply. Of course, the ultimate scarce resource is time- everyone, rich or poor, has just 24 hours in the day to try to acquire the goods they want. At any point in time, there is only a finite amount of resources available.

Think about it this way: In 2015 the labor force in the United States contained over 158.6 million workers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Similarly, the total area of the United States is 3,794,101 square miles. These are large numbers for such crucial resources, however, they are limited. Because these resources are limited, so are the numbers of goods and services we produce with them. Combine this with assumption in orthodox economics that human wants are virtually infinite, and you can see why scarcity is a problem.

In every country in the world, there are people who are hungry, homeless (for example, those who call park benches their beds, as shown in Figure 1), and in need of healthcare, just to focus on a few critical goods and services. Why is this the case? From the orthodox economic perspective scarcity is the cause. Let’s delve into the orthodox economic concept of scarcity a little deeper, because it is crucial to understanding this perspective.

The Orthodox Economic Problem of Scarcity

Every society, at every level, must make choices about how to use its resources. Families must decide whether to spend their money on a new car or a fancy vacation. Towns must choose whether to put more of the budget into police and fire protection or into the school system. Nations must decide whether to devote more funds to national defense or to protecting the environment. In most cases, there just aren’t/isn’t enough resources/money in the budget to do everything.

Think about all the things you consume: food, shelter, clothing, transportation, healthcare, and entertainment. How do you acquire those items? You do not produce them yourself. You buy them. How do you afford the things you buy? You work for pay. Or if you do not, someone else does on your behalf. Yet, what if most of us never have enough to buy all the things we want. This could be explained by scarcity. So what steps can be taken to mitigate scarcity?

The Division of and Specialization of Labor

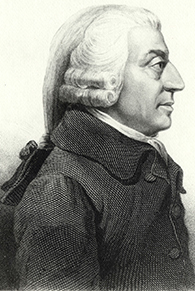

Think back to pioneer days, when individuals knew how to do so much more than we do today, from building their homes, to growing their crops, to hunting for food, to repairing their equipment. Most of us do not know how to do all—or any—of those things. It is not because we could not learn. Rather, we do not have to. The reason why is something called the division and specialization of labor, an idea first put forth by Adam Smith, Figure 2, in his book, The Wealth of Nations.

The formal study of economics began when Adam Smith (1723–1790) published his famous book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Many authors had written on economics in the centuries before Smith, but he was (at least, among) the first to comprehensively address the functioning of a capitalist market economy. In the first chapter, Smith introduces the division of labor, which means that the way a good or service is produced is divided into a number of tasks that are performed by different workers, instead of all the tasks being done by the same person.

To illustrate the division of labor, Smith counted how many tasks went into making a pin: drawing out a piece of wire, cutting it to the right length, straightening it, putting a head on one end and a point on the other, and packaging pins for sale, to name just a few. Smith counted 18 distinct tasks that were often done by different people—all for a pin, believe it or not!

Modern businesses divide tasks as well. Even a relatively simple business like a restaurant divides up the task of serving meals into a range of jobs like top chef, sous chefs, less-skilled kitchen help, servers to wait on the tables, a greeter at the door, janitors to clean up, and a business manager to handle paychecks and bills—not to mention the economic connections a restaurant has with suppliers of food, furniture, kitchen equipment, and the building where it is located. A complex business like a large manufacturing factory, such as the shoe factory shown in Figure 3, or a hospital can have hundreds of job classifications.

Why the Division of Labor Increases Production

When the tasks involved with producing a good or service are divided and subdivided, workers and businesses can produce a greater quantity of output. In his observations of pin factories, Smith observed that one worker alone might make 20 pins in a day, but that a small business of 10 workers (some of whom would need to do two or three of the 18 tasks involved with pin-making), could make 48,000 pins in a day. How can a group of workers, each specializing in certain tasks, produce so much more than the same number of workers who try to produce the entire good or service by themselves? Smith offered three reasons.

First, specialization in a particular small job allows workers to focus on specific parts of the production process which allows workers to focus on learning a limited number of tasks and to improve at performing those tasks. This pattern holds true for many workers, including assembly line laborers who build cars, stylists who cut hair, and doctors who perform heart surgery. A similar pattern often operates within businesses. In many cases, a business that focuses on one or a few products (sometimes called its “core competency”) is more successful than firms that try to make a wide range of products. Whatever the reason, specialization in production improves productivity more than if producers attempt a combination of tasks.

Second, specialization limits distractions and the loss of time associated with transitioning from one type of work to another. If a worker is responsible for one task and is then asked to do another task, it will take that worker time to adjust to the new task. Productivity that otherwise would have been generated by having a worker perform only one task will be lost as the worker transitions to another task.

Third, specialized workers often know their jobs well enough to suggest innovative ways to do their work faster and better. Frequently this means that workers improve upon the ways in which they use the tools, machines, and equipment associated with their work.

The ultimate result of workers who can focus on their preferences and talents, learn to do their specialized jobs better, and work in larger organizations is that society as a whole can produce and consume far more than if each person tried to produce all of their own goods and services.

Trade and Markets

Specialization only makes sense, though, if workers can use the pay they receive for doing their jobs to purchase the other goods and services that they need. In short, specialization requires trade.

You do not have to know anything about electronics or sound systems to play music—you just buy an iPod or MP3 player, download the music and listen. You do not have to know anything about artificial fibers or the construction of sewing machines if you need a jacket—you just buy the jacket and wear it. You do not need to know anything about internal combustion engines to operate a car—you just get in and drive. Instead of trying to acquire all the knowledge and skills involved in producing all of the goods and services that you wish to consume, the market allows you to learn a specialized set of skills and then use the pay you receive to buy the goods and services you need or want.

Summary

Orthodox economics seeks to apply the concept of scarcity, which is when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply, in the study of how a market capitalist economy functions. In a modern capitalism, the division of labor, in which people earn income by specializing in what they produce and then use that income to purchase the products they need or want, enhances productivity. The division of labor allows individuals and firms to specialize and to produce more for several reasons: a) It allows the agents to focus on areas of advantage due to natural factors and skill levels; b) It encourages the agents to learn and invent; c) It allows agents to take advantage of economies of scale. The division and specialization purportedly then enhance efficiency and allows scarce resources to be stretched further, ideally meeting an increasing amount of seemingly infinite wants.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2015. “The Employment Situation—February 2015.” Accessed March 27, 2015. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

Williamson, Lisa. “US Labor Market in 2012.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed December 1, 2013. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/03/art1full.pdf.

Glossary

- division of labor

- the way in which the work required to produce a good or service is divided into tasks performed by different workers

- economics (orthodox definition)

- the study of how humans make choices under conditions of scarcity

- economies of scale

- when the average cost of producing each individual unit declines as total output increases

- scarcity

- when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply

- specialization

- when workers or firms focus on particular tasks for which they are well-suited within the overall production process

Principles of Economics: Scarcity and Social Provisioning takes a pluralistic approach to the standard topics of introductory economics courses. The text builds on the chiefly neoclassical (or orthodox economics) material of the OpenStax Principles of Economics text, adding extensive content from heterodox economic thought. Emphasizing the importance of pluralism and critical thinking, the text presents the method and theory of neoclassical economics alongside critiques thereof and heterodox alternatives in both method and theory. This approach is taken from the outset of the text, where contrasting definitions of economics are discussed in the context of the various ways in which orthodox and heterodox economists study the subject. The same approach–of theory and method, critique, and alternative theory and method–is taken in the study of consumption, production, market exchange, macroeconomic equilibrium, fiscal and monetary policy, as well as in the applied theory chapters. Historical and contemporary examples are given throughout, and both theory and application are presented with a balanced approach.

This textbook will be of interest especially to instructors and students who wish to go beyond the traditional approach to the fundamentals of economic theory, and explore the wider spectrum of economic thought.

About the Authors

Erik Dean is an instructor of economics at Portland Community College in Portland, Oregon.

Justin Elardo is an instructor of economics at Portland Community College in Portland, Oregon.

Mitch Green is an instructor of economics at Portland Community College in Portland, Oregon.

Benjamin Wilson is an assistant professor of economics at Eastern Oregon University.

Sebastian Berger is a senior lecturer in economics at the University of the West of England - Bristol.

History of the Text

OpenStax

As noted above, the foundational content for this text comes from OpenStax. OpenStax is a non-profit organization committed to improving student access to quality learning materials. Their free textbooks go through a rigorous editorial publishing process, and are developed and peer-reviewed by educators to ensure they are readable, accurate, and meet the scope and sequence requirements of today’s college courses. Unlike traditional textbooks, OpenStax resources live online and are owned by the community of educators using them. Through partnerships with companies and foundations committed to reducing costs for students, OpenStax is working to improve access to higher education for all. OpenStax is an initiative of Rice University and is made possible through the generous support of several philanthropic foundations.

To develop Principles of Economics, OpenStax acquired the rights to Timothy Taylor’s second edition of Principles of Economics and solicited ideas from economics instructors at all levels of higher education, from community colleges to Ph.D.-granting universities. The pedagogical choices, chapter arrangements, and learning objective fulfillment were developed and vetted with feedback from educators dedicated to the project. They thoroughly read the material and offered critical and detailed commentary. The outcome was a balanced approach to micro and macro economics, to both Keynesian and classical views, and to the theory and application of economics concepts. Data current as of 2015 are incorporated for topics that range from average U.S. household consumption to the total value of all home equity. Current events are treated in a politically-balanced way as well.

Pluralist Project

The current text, emphasizing a pluralist approach, began with the awarding of an Open Oregon grant in 2016. That grant allowed the authors to develop a pluralist textbook for introductory microeconomics courses. The text has since been expanded to cover both micro- and macroeconomics.

Organization of the Book

The book is organized into four main parts:

- Introduction. Including a look at the various ways that economists, orthodox and heterodox, define the subject

- Metal and Modern Money. The macroeconomics section, differentiating orthodox and heterodox perspectives by the traditional divide between neoclassical and post Keynesian theorists.

- Markets and Management. The microeconomics section, differentiating orthodox and heterodox perspectives with a focus, for the latter, on institutionalist and post Keynesian perspectives.

- International Economics. Introduces the international dimensions of economics, including international trade and protectionism.

About the OpenStax Team

Senior Contributing Author

Timothy Taylor, Macalester College

Timothy Taylor has been writing and teaching about economics for 30 years, and is the Managing Editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a post he’s held since 1986. He has been a lecturer for The Teaching Company, the University of Minnesota, and the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, where students voted him Teacher of the Year in 1997. His writings include numerous pieces for journals such as the Milken Institute Review and The Public Interest, and he has been an editor on many projects, most notably for the Brookings Institution and the World Bank, where he was Chief Outside Editor for the World Development Report 1999/2000, Entering the 21st Century: The Changing Development Landscape. He also blogs four to five times per week at http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com. Timothy Taylor lives near Minneapolis with his wife Kimberley and their three children.

Steven A. Greenlaw, University of Mary Washington

Steven Greenlaw has been teaching principles of economics for more than 30 years. In 1999, he received the Grellet C. Simpson Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching at the University of Mary Washington. He is the author of Doing Economics: A Guide to Doing and Understanding Economic Research, as well as a variety of articles on economics pedagogy and instructional technology, published in the Journal of Economic Education, the International Review of Economic Education, and other outlets. He wrote the module on Quantitative Writing for Starting Point: Teaching and Learning Economics, the web portal on best practices in teaching economics. Steven Greenlaw lives in Alexandria, Virginia with his wife Kathy and their three children.

Contributing Authors

| Eric Dodge | Hanover College |

| Cynthia Gamez | University of Texas at El Paso |

| Andres Jauregui | Columbus State University |

| Diane Keenan | Cerritos College |

| Dan MacDonald | California State University San Bernardino |

| Amyaz Moledina | The College of Wooster |

| Craig Richardson | Winston-Salem State University |

| David Shapiro | Pennsylvania State University |

| Ralph Sonenshine | American University |

Expert Reviewers

| Bryan Aguiar | Northwest Arkansas Community College |

| Basil Al Hashimi | Mesa Community College |

| Emil Berendt | Mount St. Mary’s University |

| Zena Buser | Adams State University |

| Douglas Campbell | The University of Memphis |

| Sanjukta Chaudhuri | University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire |

| Xueyu Cheng | Alabama State University |

| Robert Cunningham | Alma College |

| Rosa Lea Danielson | College of DuPage |

| Steven Deloach | Elon University |

| Debbie Evercloud | University of Colorado Denver |

| Sal Figueras | Hudson County Community College |

| Reza Ghorashi | Richard Stockton College of New Jersey |

| Robert Gillette | University of Kentucky |

| Shaomin Huang | Lewis-Clark State College |

| George Jones | University of Wisconsin-Rock County |

| Charles Kroncke | College of Mount St. Joseph |

| Teresa Laughlin | Palomar Community College |

| Carlos Liard-Muriente | Central Connecticut State University |

| Heather Luea | Kansas State University |

| Steven Lugauer | University of Notre Dame |

| William Mosher | Nashua Community College |

| Michael Netta | Hudson County Community College |

| Nick Noble | Miami University |

| Joe Nowakowski | Muskingum University |

| Shawn Osell | University of Wisconsin, Superior |

| Mark Owens | Middle Tennessee State University |

| Sonia Pereira | Barnard College |

| Brian Peterson | Central College |

| Jennifer Platania | Elon University |

| Robert Rycroft | University of Mary Washington |

| Adrienne Sachse | Florida State College at Jacksonville |

| Hans Schumann | Texas AM |

| Gina Shamshak | Goucher College |

| Chris Warburton | John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY |

| Mark Witte | Northwestern |

| Chiou-nan Yeh | Alabama State University |

Ancillaries

Instructors may contact Open Oregon Educational Resources for quiz question test banks associated with each chapter.

Copyright

© May 18, 2016 OpenStax Economics. Textbook content produced by OpenStax Economics as well as by the present authors are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license.

For questions regarding this license, please contact partners@openstaxcollege.org.

Keywords/Tags:

Economics, Microeconomics, Macroeconomics, Introductory

Copyright: 2016 by Rice University; 2020 Erik Dean, Justin Elardo, Mitch Green, Benjamin Wilson, Sebastian Berger.

Inflation Chapter

Self-Check Questions

[link] shows the fruit prices that the typical college student purchased from 2001 to 2004. What is the amount spent each year on the "basket" of fruit with the quantities shown in column 2?

| Items | Qty | (2001) Price | (2001) Amount Spent | (2002) Price | (2002) Amount Spent | (2003) Price | (2003) Amount Spent | (2004) Price | (2004) Amount Spent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apples | 10 | $0.50 | $0.75 | $0.85 | $0.88 | ||||

| Bananas | 12 | $0.20 | $0.25 | $0.25 | $0.29 | ||||

| Grapes | 2 | $0.65 | $0.70 | $0.90 | $0.95 | ||||

| Raspberries | 1 | $2.00 | $1.90 | $2.05 | $2.13 | $2.13 | |||

| Total |

[reveal-answer q="904989"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="904989"]

To compute the amount spent on each fruit in each year, you multiply the quantity of each fruit by the price.

- 10 apples × 50 cents each = $5.00 spent on apples in 2001.

- 12 bananas × 20 cents each = $2.40 spent on bananas in 2001.

- 2 bunches of grapes at 65 cents each = $1.30 spent on grapes in 2001.

- 1 pint of raspberries at $2 each = $2.00 spent on raspberries in 2001.

Adding up the amounts gives you the total cost of the fruit basket. The total cost of the fruit basket in 2001 was $5.00 + $2.40 + $1.30 + $2.00 = $10.70. The total costs for all the years are shown in the following table.

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|

| $10.70 | $13.80 | $15.35 | $16.31 |

[/hidden-answer]

Construct the price index for a "fruit basket" in each year using 2003 as the base year.

[reveal-answer q="769"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="769"]

If 2003 is the base year, then the index number has a value of 100 in 2003. To transform the cost of a fruit basket each year, we divide each year’s value by $15.35, the value of the base year, and then multiply the result by 100. The price index is shown in the following table.

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 69.71 | 89.90 | 100.00 | 106.3 |

Note that the base year has a value of 100; years before the base year have values less than 100; and years after have values more than 100.[/hidden-answer]

Compute the inflation rate for fruit prices from 2001 to 2004.

[reveal-answer q="861842"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="861842"]The inflation rate is calculated as the percentage change in the price index from year to year. For example, the inflation rate between 2001 and 2002 is (84.61 – 69.71) / 69.71 = 0.2137 = 21.37%. The inflation rates for all the years are shown in the last row of the following table, which includes the two previous answers.

| Items | Qty | (2001) Price | (2001) Amount Spent | (2002) Price | (2002) Amount Spent | (2003) Price | (2003) Amount Spent | (2004) Price | (2004) Amount Spent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apples | 10 | $0.50 | $5.00 | $0.75 | $7.50 | $0.85 | $8.50 | $0.88 | $8.80 |

| Bananas | 12 | $0.20 | $2.40 | $0.25 | $3.00 | $0.25 | $3.00 | $0.29 | $3.48 |

| Grapes | 2 | $0.65 | $1.30 | $0.70 | $1.40 | $0.90 | $1.80 | $0.95 | $1.90 |

| Raspberries | 1 | $2.00 | $2.00 | $1.90 | $1.90 | $2.05 | $2.05 | $2.13 | $2.13 |

| Total | $10.70 | $13.80 | $15.35 | $16.31 | |||||

| Price Index | 69.71 | 84.61 | 100.00 | 106.3 | |||||

| Inflation Rate | 21.37% | 18.19% | 6.3% |

[/hidden-answer]

Edna is living in a retirement home where most of her needs are taken care of, but she has some discretionary spending. Based on the basket of goods in [link], by what percentage does Edna’s cost of living increase between time 1 and time 2?

| Items | Quantity | (Time 1) Price | (Time 2) Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gifts for grandchildren | 12 | $50 | $60 |

| Pizza delivery | 24 | $15 | $16 |

| Blouses | 6 | $60 | $50 |

| Vacation trips | 2 | $400 | $420 |

[reveal-answer q="548585"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="548585"]Begin by calculating the total cost of buying the basket in each time period, as shown in the following table.

| Items | Quantity | (Time 1) Price | (Time 1) Total Cost | (Time 2) Price | (Time 2) Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gifts | 12 | $50 | $600 | $60 | $720 |

| Pizza | 24 | $15 | $360 | $16 | $384 |

| Blouses | 6 | $60 | $360 | $50 | $300 |

| Trips | 2 | $400 | $800 | $420 | $840 |

| Total Cost | $2,120 | $2,244 |

The rise in cost of living is calculated as the percentage increase:

(2244 – 2120) / 2120 = 0.0585 = 5.85%.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

How do economists use a basket of goods and services to measure the price level?

Why do economists use index numbers to measure the price level rather than dollar value of goods?

What is the difference between the price level and the rate of inflation?

Critical Thinking Question

Inflation rates, like most statistics, are imperfect measures. Can you identify some ways that the inflation rate for fruit does not perfectly capture the rising price of fruit?

Problems

The index number representing the price level changes from 110 to 115 in one year, and then from 115 to 120 the next year. Since the index number increases by five each year, is five the inflation rate each year? Is the inflation rate the same each year? Explain your answer.

The total price of purchasing a basket of goods in the United Kingdom over four years is: year 1=£940, year 2=£970, year 3=£1000, and year 4=£1070. Calculate two price indices, one using year 1 as the base year (set equal to 100) and the other using year 4 as the base year (set equal to 100). Then, calculate the inflation rate based on the first price index. If you had used the other price index, would you get a different inflation rate? If you are unsure, do the calculation and find out.

Self-Check Questions

How to Measure Changes in the Cost of Living introduced a number of different price indices. Which price index would be best to use to adjust your paycheck for inflation?

[reveal-answer q="774973"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="774973"]Since the CPI measures the prices of the goods and services purchased by the typical urban consumer, it measures the prices of things that people buy with their paycheck. For that reason, the CPI would be the best price index to use for this purpose.[/hidden-answer]

The Consumer Price Index is subject to the substitution bias and the quality/new goods bias. Are the Producer Price Index and the GDP Deflator also subject to these biases? Why or why not?

[reveal-answer q="453751"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="453751"]The PPI is subject to those biases for essentially the same reasons as the CPI is. The GDP deflator picks up prices of what is actually purchased that year, so there are no biases. That is the advantage of using the GDP deflator over the CPI.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

Why does "substitution bias" arise if we calculate the inflation rate based on a fixed basket of goods?

Why does the "quality/new goods bias" arise if we calculate the inflation rate based on a fixed basket of goods?

Critical Thinking Question

Given the federal budget deficit in recent years, some economists have argued that by adjusting Social Security payments for inflation using the CPI, Social Security is overpaying recipients. What is their argument, and do you agree or disagree with it?

Why is the GDP deflator not an accurate measure of inflation as it impacts a household?

Imagine that the government statisticians who calculate the inflation rate have been updating the basic basket of goods once every 10 years, but now they decide to update it every five years. How will this change affect the amount of substitution bias and quality/new goods bias?

Describe a situation, either a government policy situation, an economic problem, or a private sector situation, where using the CPI to convert from nominal to real would be more appropriate than using the GDP deflator.

Describe a situation, either a government policy situation, an economic problem, or a private sector situation, where using the GDP deflator to convert from nominal to real would be more appropriate than using the CPI.

Self-Check Question

Go to this website for the Purchasing Power Calculator at MeasuringWorth.com. How much money would it take today to purchase what one dollar would have bought in the year of your birth?

[reveal-answer q="746759"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="746759"]

The calculator requires you to input three numbers:

- The first year, in this case the year of your birth

- The amount of money you would want to translate in terms of its purchasing power

- The last year—now or the most recent year the calculator will accept

My birth year is 1955. The amount is $1. The year 2012 is currently the latest year the calculator will accept. The simple purchasing power calculator shows that $1 of purchases in 1955 would cost $8.57 in 2012. The website also explains how the true answer is more complicated than that shown by the simple purchasing power calculator.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What has been a typical range of inflation in the U.S. economy in the last decade or so?

Over the last century, during what periods was the U.S. inflation rate highest and lowest?

What is deflation?

Critical Thinking Question

Why do you think the U.S. experience with inflation over the last 50 years has been so much milder than in many other countries?

Problems

Within 1 or 2 percentage points, what has the U.S. inflation rate been during the last 20 years? Draw a graph to show the data.

Self-Check Question

If inflation rises unexpectedly by 5%, would a state government that had recently borrowed money to pay for a new highway benefit or lose?

[reveal-answer q="228091"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="228091"]The state government would benefit because it would repay the loan in less valuable dollars than it borrowed. Plus, tax revenues for the state government would increase because of the inflation.[/hidden-answer]

Review Question

Identify several parties likely to be helped and hurt by inflation.

Critical Thinking Questions

If, over time, wages and salaries on average rise at least as fast as inflation, why do people worry about how inflation affects incomes?

Who in an economy is the big winner from inflation?

Self-Check Questions

How should an increase in inflation affect the interest rate on an adjustable-rate mortgage?

[reveal-answer q="802598"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="802598"]Higher inflation reduces real interest rates on fixed rate mortgages. Because ARMs can be adjusted, higher inflation leads to higher interest rates on ARMs.[/hidden-answer]

A fixed-rate mortgage has the same interest rate over the life of the loan, whether the mortgage is for 15 or 30 years. By contrast, an adjustable-rate mortgage changes with market interest rates over the life of the mortgage. If inflation falls unexpectedly by 3%, what would likely happen to a homeowner with an adjustable-rate mortgage?

[reveal-answer q="892510"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="892510"]Because the mortgage has an adjustable rate, the rate should fall by 3%, the same as inflation, to keep the real interest rate the same.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What is indexing?

Name several forms of indexing in the private and public sector.

Critical Thinking Questions

If a government gains from unexpected inflation when it borrows, why would it choose to offer indexed bonds?

Do you think perfect indexing is possible? Why or why not?

Problems

If inflation rises unexpectedly by 5%, indicate for each of the following whether the economic actor is helped, hurt, or unaffected:

- A union member with a COLA wage contract

- Someone with a large stash of cash in a safe deposit box

- A bank lending money at a fixed rate of interest

- A person who is not due to receive a pay raise for another 11 months

Rosalie the Retiree knows that when she retires in 16 years, her company will give her a one-time payment of $20,000. However, if the inflation rate is 6% per year, how much buying power will that $20,000 have when measured in today’s dollars? Hint: Start by calculating the rise in the price level over the 16 years.

International Trade and Capital Flow Chapter

Self-Check Questions

If foreign investors buy more U.S. stocks and bonds, how would that show up in the current account balance?

[reveal-answer q="126832"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="126832"]The stock and bond values will not show up in the current account. However, the dividends from the stocks and the interest from the bonds show up as an import to income in the current account.[/hidden-answer]

If the trade deficit of the United States increases, how is the current account balance affected?

[reveal-answer q="813802"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="813802"]It becomes more negative as imports, which are a negative to the current account, are growing faster than exports, which are a positive.[/hidden-answer]

State whether each of the following events involves a financial flow to the Mexican economy or a financial flow out of the Mexican economy:

- Mexico imports services from Japan

- Mexico exports goods to Canada

- U.S. investors receive a return from past financial investments in Mexico

[reveal-answer q="750414"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="750414"]

- Money flows out of the Mexican economy.

- Money flows into the Mexican economy.

- Money flows out of the Mexican economy.

[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

If imports exceed exports, is it a trade deficit or a trade surplus? What about if exports exceed imports?

What is included in the current account balance?

Critical Thinking Questions

Occasionally, a government official will argue that a country should strive for both a trade surplus and a healthy inflow of capital from abroad. Explain why such a statement is economically impossible.

A government official announces a new policy. The country wishes to eliminate its trade deficit, but will strongly encourage financial investment from foreign firms. Explain why such a statement is contradictory.

Problems

In 2001, the United Kingdom's economy exported goods worth £192 billion and services worth another £77 billion. It imported goods worth £225 billion and services worth £66 billion. Receipts of income from abroad were £140 billion while income payments going abroad were £131 billion. Government transfers from the United Kingdom to the rest of the world were £23 billion, while various U.K government agencies received payments of £16 billion from the rest of the world.

- Calculate the U.K. merchandise trade deficit for 2001.

- Calculate the current account balance for 2001.

- Explain how you decided whether payments on foreign investment and government transfers counted on the positive or the negative side of the current account balance for the United Kingdom in 2001.

Self-Check Questions

In what way does comparing a country’s exports to GDP reflect its degree of globalization?

[reveal-answer q="479611"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="479611"]GDP is a dollar value of all production of goods and services. Exports are produced domestically but shipped abroad. The percent ratio of exports to GDP gives us an idea of how important exports are to the national economy out of all goods and services produced. For example, exports represent only 14% of U.S. GDP, but 50% of Germany’s GDP[/hidden-answer]

At one point Canada’s GDP was $1,800 billion and its exports were $542 billion. What was Canada’s export ratio at this time?

[reveal-answer q="73675"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="73675"]Divide $542 billion by $1,800 billion.[/hidden-answer]

The GDP for the United States is $18,036 billion and its current account balance is –$484 billion. What percent of GDP is the current account balance?

[reveal-answer q="509848"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="509848"]Divide –$400 billion by $16,800 billion.[/hidden-answer]

Why does the trade balance and the current account balance track so closely together over time?

[reveal-answer q="7035"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="7035"]The trade balance is the difference between exports and imports. The current account balance includes this number (whether it is a trade balance or a trade surplus), but also includes international flows of money from global investments.[/hidden-answer]

Review Question

In recent decades, has the U.S. trade balance usually been in deficit, surplus, or balanced?

Critical Thinking Questions

If a country is a big exporter, is it more exposed to global financial crises?

If countries reduced trade barriers, would the international flows of money increase?

Self-Check Questions

State whether each of the following events involves a financial flow to the U.S. economy or away from the U.S. economy:

- Export sales to Germany

- Returns paid on past U.S. financial investments in Brazil

- Foreign aid from the U.S. government to Egypt

- Imported oil from the Russian Federation

- Japanese investors buying U.S. real estate

[reveal-answer q="515704"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="515704"]

- An export sale to Germany involves a financial flow from Germany to the U.S. economy.

- The issue here is not U.S. investments in Brazil, but the return paid on those investments, which involves a financial flow from the Brazilian economy to the U.S. economy.

- Foreign aid from the United States to Egypt is a financial flow from the United States to Egypt.

- Importing oil from the Russian Federation means a flow of financial payments from the U.S. economy to the Russian Federation.

- Japanese investors buying U.S. real estate is a financial flow from Japan to the U.S. economy. How does the bottom portion of

[/hidden-answer]

[link], showing the international flow of investments and capital, differ from the upper portion?

[reveal-answer q="408966"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="408966"]The top portion tracks the flow of exports and imports and the payments for those. The bottom portion is looking at international financial investments and the outflow and inflow of monies from those investments. These investments can include investments in stocks and bonds or real estate abroad, as well as international borrowing and lending.[/hidden-answer]

Explain the relationship between a current account deficit or surplus and the flow of funds.

[reveal-answer q="9618"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="9618"]If more monies are flowing out of the country (for example, to pay for imports) it will make the current account more negative or less positive, and if more monies are flowing into the country, it will make the current account less negative or more positive.[/hidden-answer]

Review Question

Does a trade surplus mean an overall inflow of financial capital to an economy, or an overall outflow of financial capital? What about a trade deficit?

Critical Thinking Question

Is it better for your country to be an international lender or borrower?

Self-Check Questions

Using the national savings and investment identity, explain how each of the following changes (ceteris paribus) will increase or decrease the trade balance:

- A lower domestic savings rate

- The government changes from running a budget surplus to running a budget deficit

- The rate of domestic investment surges

[reveal-answer q="175665"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="175665"]Write out the national savings and investment identity for the situation of the economy implied by this question:

[latex]\begin{array}{rcl}\text{Supply of capital}& \text{ = }& \text{Demand for capital}\\ \text{S +\hspace{0.17em} (M - X) + (T - G)}& \text{ = }& \text{I} \\ \text{Savings +\hspace{0.17em} (trade deficit) +\hspace{0.17em} (government budget surplus)}& \text{=}& \text{Investment}\end{array}[/latex]

If domestic savings increases and nothing else changes, then the trade deficit will fall. In effect, the economy would be relying more on domestic capital and less on foreign capital. If the government starts borrowing instead of saving, then the trade deficit must rise. In effect, the government is no longer providing savings and so, if nothing else is to change, more investment funds must arrive from abroad. If the rate of domestic investment surges, then, ceteris paribus, the trade deficit must also rise, to provide the extra capital. The ceteris paribus—or "other things being equal"—assumption is important here. In all of these situations, there is no reason to expect in the real world that the original change will affect only, or primarily, the trade deficit. The identity only says that something will adjust—it does not specify what.[/hidden-answer]

If a country is running a government budget surplus, why is (T – G) on the left side of the saving-investment identity?

[reveal-answer q="926062"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="926062"]The government is saving rather than borrowing. The supply of savings, whether private or public, is on the left side of the identity.[/hidden-answer]

What determines the size of a country’s trade deficit?

[reveal-answer q="589459"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="589459"]A trade deficit is determined by a country’s level of private and public savings and the amount of domestic investment.[/hidden-answer]

If domestic investment increases, and there is no change in the amount of private and public saving, what must happen to the size of the trade deficit?

[reveal-answer q="294694"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="294694"]The trade deficit must increase. To put it another way, this increase in investment must be financed by an inflow of financial capital from abroad.[/hidden-answer]

Why does a recession cause a trade deficit to increase?

[reveal-answer q="845118"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="845118"]Incomes fall during a recession, and consumers buy fewer good, including imports.[/hidden-answer]

Both the United States and global economies are booming. Will U.S. imports and/or exports increase?

[reveal-answer q="491913"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="491913"]A booming economy will increase the demand for goods in general, so import sales will increase. If our trading partners’ economies are doing well, they will buy more of our products and so U.S. exports will increase.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What are the two main sides of the national savings and investment identity?

What are the main components of the national savings and investment identity?

Critical Thinking Questions

Many think that the size of a trade deficit is due to a lack of competitiveness of domestic sectors, such as autos. Explain why this is not true.

If you observed a country with a rapidly growing trade surplus over a period of a year or so, would you be more likely to believe that the country's economy was in a period of recession or of rapid growth? Explain.

Occasionally, a government official will argue that a country should strive for both a trade surplus and a healthy inflow of capital from abroad. Is this possible?

Problems

Imagine that the U.S. economy finds itself in the following situation: a government budget deficit of $100 billion, total domestic savings of $1,500 billion, and total domestic physical capital investment of $1,600 billion. According to the national saving and investment identity, what will be the current account balance? What will be the current account balance if investment rises by $50 billion, while the budget deficit and national savings remain the same?

[link] provides some hypothetical data on macroeconomic accounts for three countries represented by A, B, and C and measured in billions of currency units. In [link], private household saving is SH, tax revenue is T, government spending is G, and investment spending is I.

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SH | 700 | 500 | 600 |

| T | 00 | 500 | 500 |

| G | 600 | 350 | 650 |

| I | 800 | 400 | 450 |

- Calculate the trade balance and the net inflow of foreign saving for each country.

- State whether each one has a trade surplus or deficit (or balanced trade).

- State whether each is a net lender or borrower internationally and explain.

Imagine that the economy of Germany finds itself in the following situation: the government budget has a surplus of 1% of Germany’s GDP; private savings is 20% of GDP; and physical investment is 18% of GDP.

- Based on the national saving and investment identity, what is the current account balance?

- If the government budget surplus falls to zero, how will this affect the current account balance?

Self-Check Questions

For each of the following, indicate which type of government spending would justify a budget deficit and which would not.

- Increased federal spending on Medicare

- Increased spending on education

- Increased spending on the space program

- Increased spending on airports and air traffic control

[reveal-answer q="453339"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="453339"]a. Increased federal spending on Medicare may not increase productivity, so a budget deficit is not justified.

b. Increased spending on education will increase productivity and foster greater economic growth, so a budget deficit is justified.

c. Increased spending on the space program may not increase productivity, so a budget deficit is not justified.

d. Increased spending on airports and air traffic control will increase productivity and foster greater economic growth, so a budget deficit is justified.[/hidden-answer]

How did large trade deficits hurt the East Asian countries in the mid 1980s? (Recall that trade deficits are equivalent to inflows of financial capital from abroad.)

[reveal-answer q="532520"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="532520"]Foreign investors worried about repayment so they began to pull money out of these countries. The money can be pulled out of stock and bond markets, real estate, and banks.[/hidden-answer]

Describe a scenario in which a trade surplus benefits an economy and one in which a trade surplus is occurring in an economy that performs poorly. What key factor or factors are making the difference in the outcome that results from a trade surplus?

[reveal-answer q="873126"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="873126"]A rapidly growing trade surplus could result from a number of factors, so you would not want to be too quick to assume a specific cause. However, if the choice is between whether the economy is in recession or growing rapidly, the answer would have to be recession. In a recession, demand for all goods, including imports, has declined; however, demand for exports from other countries has not necessarily altered much, so the result is a larger trade surplus.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

When is a trade deficit likely to work out well for an economy? When is it likely to work out poorly?

Does a trade surplus help to guarantee strong economic growth?

Critical Thinking Question

What is more important, a country’s current account balance or GDP growth? Why?

Self-Check Questions

The United States exports 14% of GDP while Germany exports about 50% of its GDP. Explain what that means.

[reveal-answer q="901034"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="901034"]Germany has a higher level of trade than the United States. The United States has a large domestic economy so it has a large volume of internal trade.[/hidden-answer]

Explain briefly whether each of the following would be more likely to lead to a higher level of trade for an economy, or a greater imbalance of trade for an economy.

- Living in an especially large country

- Having a domestic investment rate much higher than the domestic savings rate

- Having many other large economies geographically nearby

- Having an especially large budget deficit

- Having countries with a tradition of strong protectionist legislation shutting out imports

[reveal-answer q="659515"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="659515"]a. A large economy tends to have lower levels of international trade, because it can do more of its trade internally, but this has little impact on its trade imbalance.

b. An imbalance between domestic physical investment and domestic saving (including government and private saving) will always lead to a trade imbalance, but has little to do with the level of trade.

c. Many large trading partners nearby geographically increases the level of trade, but has little impact one way or the other on a trade imbalance.

d. The answer here is not obvious. An especially large budget deficit means a large demand for financial capital which, according to the national saving and investment identity, makes it somewhat more likely that there will be a need for an inflow of foreign capital, which means a trade deficit.

e. A strong tradition of discouraging trade certainly reduces the level of trade. However, it does not necessarily say much about the balance of trade, since this is determined by both imports and exports, and by national levels of physical investment and savings.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What three factors will determine whether a nation has a higher or lower share of trade relative to its GDP?

What is the difference between trade deficits and balance of trade?

Critical Thinking Questions

Will nations that are more involved in foreign trade tend to have higher trade imbalances, lower trade imbalances, or is the pattern unpredictable?

Some economists warn that the persistent trade deficits and a negative current account balance that the United States has run will be a problem in the long run. Do you agree or not? Explain your answer.

Chapter 6 (now 4)

Section 6.1

Self-Check Questions

Country A has export sales of $20 billion, government purchases of $1,000 billion, business investment is $50 billion, imports are $40 billion, and consumption spending is $2,000 billion. What is the dollar value of GDP?

[reveal-answer q="293818"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="293818"]GDP is C + I + G + (X – M). GDP = $2,000 billion + $50 billion + $1,000 billion + ($20 billion – $40 billion) = $3,030[/hidden-answer]

Which of the following are included in GDP, and which are not?

- The cost of hospital stays

- The rise in life expectancy over time

- Child care provided by a licensed day care center

- Child care provided by a grandmother

- A used car sale

- A new car sale

- The greater variety of cheese available in supermarkets

- The iron that goes into the steel that goes into a refrigerator bought by a consumer.

[reveal-answer q="23073"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="23073"]

- Hospital stays are part of GDP.

- Changes in life expectancy are not market transactions and not part of GDP.

- Child care that is paid for is part of GDP.

- If Grandma gets paid and reports this as income, it is part of GDP, otherwise not.

- A used car is not produced this year, so it is not part of GDP.

- A new car is part of GDP.

- Variety does not count in GDP, where the cheese could all be cheddar.

- The iron is not counted because it is an intermediate good.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What are the main components of measuring GDP with what is demanded?

What are the main components of measuring GDP with what is produced?

Would you usually expect GDP as measured by what is demanded to be greater than GDP measured by what is supplied, or the reverse?

Why must you avoid double counting when measuring GDP?

Critical Thinking Question

U.S. macroeconomic data are among the best in the world. Given what you learned in the Clear It Up "How do statisticians measure GDP?", does this surprise you, or does this simply reflect the complexity of a modern economy?

What does GDP not tell us about the economy?

Problem

Last year, a small nation with abundant forests cut down $200 worth of trees. It then turned $100 worth of trees into $150 worth of lumber. It used $100 worth of that lumber to produce $250 worth of bookshelves. Assuming the country produces no other outputs, and there are no other inputs used in producing trees, lumber, and bookshelves, what is this nation's GDP? In other words, what is the value of the final goods the nation produced including trees, lumber and bookshelves?

Section 6.2

Self-Check Question

Using data from [link] how much of the nominal GDP growth from 1980 to 1990 was real GDP and how much was inflation?

[reveal-answer q="349098"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="349098"]From 1980 to 1990, real GDP grew by (8,225.0 – 5,926.5) / (5,926.5) = 39%. Over the same period, prices increased by (72.7 – 48.3) / (48.3/100) = 51%. So about 57% of the growth 51 / (51 + 39) was inflation, and the remainder: 39 / (51 + 39) = 43% was growth in real GDP.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What is the difference between a series of economic data over time measured in nominal terms versus the same data series over time measured in real terms?

How do you convert a series of nominal economic data over time to real terms?

Critical Thinking Question

Should people typically pay more attention to their real income or their nominal income? If you choose the latter, why would that make sense in today’s world? Would your answer be the same for the 1970s?

Problems

The "prime" interest rate is the rate that banks charge their best customers. Based on the nominal interest rates and inflation rates in [link], in which of the years would it have been best to be a lender? Based on the nominal interest rates and inflation rates in [link], in which of the years given would it have been best to be a borrower?

| Year | Prime Interest Rate | Inflation Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 7.9% | 5.7% |

| 1974 | 10.8% | 11.0% |

| 1978 | 9.1% | 7.6% |

| 1981 | 18.9% | 10.3% |

A mortgage loan is a loan that a person makes to purchase a house. [link] provides a list of the mortgage interest rate for several different years and the rate of inflation for each of those years. In which years would it have been better to be a person borrowing money from a bank to buy a home? In which years would it have been better to be a bank lending money?

| Year | Mortgage Interest Rate | Inflation Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 12.4% | 4.3% |

| 1990 | 10% | 5.4% |

| 2001 | 7.0% | 2.8% |

Section 6.3

Self-Check Questions

Without looking at [link], return to [link]. If we define a recession as a significant decline in national output, can you identify any post-1960 recessions in addition to the 2008-2009 recession? (This requires a judgment call.)

[reveal-answer q="243710"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="243710"]Two other major recessions are visible in the figure as slight dips: those of 1973–1975, and 1981–1982. Two other recessions appear in the figure as a flattening of the path of real GDP. These were in 1990–1991 and 2001.[/hidden-answer]

According to [link], how often have recessions occurred since the end of World War II (1945)?

[reveal-answer q="28688"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="28688"]11 recessions in approximately 70 years averages about one recession every six years.[/hidden-answer]

According to [link], how long has the average recession lasted since the end of World War II?

[reveal-answer q="702472"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="702472"]The table lists the "Months of Contraction" for each recession. Averaging these figures for the post-WWII recessions gives an average duration of 11 months, or slightly less than a year.[/hidden-answer]

According to [link], how long has the average expansion lasted since the end of World War II?

[reveal-answer q="393375"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="393375"]The table lists the "Months of Expansion." Averaging these figures for the post-WWII expansions gives an average expansion of 60.5 months, or more than five years.[/hidden-answer]

Review Question

What are typical GDP patterns for a high-income economy like the United States in the long run and the short run?

Critical Thinking Questions

Why do you suppose that U.S. GDP is so much higher today than 50 or 100 years ago?

Why do you think that GDP does not grow at a steady rate, but rather speeds up and slows down?

Section 6.4

Self-Check Question

Is it possible for GDP to rise while at the same time per capita GDP is falling? Is it possible for GDP to fall while per capita GDP is rising?

[reveal-answer q="245990"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="245990"]Yes. The answer to both questions depends on whether GDP is growing faster or slower than population. If population grows faster than GDP, GDP increases, while GDP per capita decreases. If GDP falls, but population falls faster, then GDP decreases, while GDP per capita increases.[/hidden-answer]

The Central African Republic has a GDP of 1,107,689 million CFA francs and a population of 4.862 million. The exchange rate is 284.681CFA francs per dollar. Calculate the GDP per capita of Central African Republic.

[reveal-answer q="940166"]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="940166"]Start with Central African Republic’s GDP measured in francs. Divide it by the exchange rate to convert to U.S. dollars, and then divide by population to obtain the per capita figure. That is, 1,107,689 million francs / 284.681 francs per dollar / 4.862 million people = $800.28 GDP per capita.[/hidden-answer]

Review Question

What are the two main difficulties that arise in comparing different countries's GDP?

Critical Thinking Question

Cross country comparisons of GDP per capita typically use purchasing power parity equivalent exchange rates, which are a measure of the long run equilibrium value of an exchange rate. In fact, we used PPP equivalent exchange rates in this module. Why could using market exchange rates, which sometimes change dramatically in a short period of time, be misleading?

Why might per capita GDP be only an imperfect measure of a country’s standard of living?

Problems

Ethiopia has a GDP of $8 billion (measured in U.S. dollars) and a population of 55 million. Costa Rica has a GDP of $9 billion (measured in U.S. dollars) and a population of 4 million. Calculate the per capita GDP for each country and identify which one is higher.

In 1980, Denmark had a GDP of $70 billion (measured in U.S. dollars) and a population of 5.1 million. In 2000, Denmark had a GDP of $160 billion (measured in U.S. dollars) and a population of 5.3 million. By what percentage did Denmark’s GDP per capita rise between 1980 and 2000?

The Czech Republic has a GDP of 1,800 billion koruny. The exchange rate is 25 koruny/U.S. dollar. The Czech population is 20 million. What is the GDP per capita of the Czech Republic expressed in U.S. dollars?

Section 6.5

Self-Check Question

Explain briefly whether each of the following would cause GDP to overstate or understate the degree of change in the broad standard of living.

- The environment becomes dirtier

- The crime rate declines

- A greater variety of goods become available to consumers

- Infant mortality declines

[reveal-answer q="740578"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="740578"]a. A dirtier environment would reduce the broad standard of living, but not be counted in GDP, so a rise in GDP would overstate the standard of living.

b. A lower crime rate would raise the broad standard of living, but not be counted directly in GDP, and so a rise in GDP would understate the standard of living.

c. A greater variety of goods would raise the broad standard of living, but not be counted directly in GDP, and so a rise in GDP would understate the rise in the standard of living.

d. A decline in infant mortality would raise the broad standard of living, but not be counted directly in GDP, and so a rise in GDP would understate the rise in the standard of living.[/hidden-answer]

Review Question

List some of the reasons why economists should not consider GDP an effective measure of the standard of living in a country.

Critical Thinking Questions

How might you measure a "green" GDP?

Chapter 7 (now 5)

Section 7.1

Self-Check Questions

Explain what the Industrial Revolution was and where it began.

[reveal-answer q="792809"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="792809"]The Industrial Revolution refers to the widespread use of power-driven machinery and the economic and social changes that resulted in the first half of the 1800s. Ingenious machines—the steam engine, the power loom, and the steam locomotive—performed tasks that would have taken vast numbers of workers to do. The Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain, and soon spread to the United States, Germany, and other countries.[/hidden-answer]

Explain the difference between property rights and contractual rights. Why do they matter to economic growth?

[reveal-answer q="472759"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="472759"]Property rights are the rights of individuals and firms to own property and use it as they see fit. Contractual rights are based on property rights and they allow individuals to enter into agreements with others regarding the use of their property providing recourse through the legal system in the event of noncompliance. Economic growth occurs when the standard of living increases in an economy, which occurs when output is increasing and incomes are rising. For this to happen, societies must create a legal environment that gives individuals the ability to use their property to their fullest and highest use, including the right to trade or sell that property. Without a legal system that enforces contracts, people would not be likely to enter into contracts for current or future services because of the risk of non-payment. This would make it difficult to transact business and would slow economic growth.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

How did the Industrial Revolution increase the economic growth rate and income levels in the United States?

How much should a nation be concerned if its rate of economic growth is just 2% slower than other nations?

Critical Thinking Question

Over the past 50 years, many countries have experienced an annual growth rate in real GDP per capita greater than that of the United States. Some examples are China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Does that mean the United States is regressing relative to other countries? Does that mean these countries will eventually overtake the United States in terms of the growth rate of real GDP per capita? Explain.

Section 7.2

Self-Check Questions

Are there other ways in which we can measure productivity besides the amount produced per hour of work?

[reveal-answer q="631548"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="631548"]Yes. Since productivity is output per unit of input, we can measure productivity using GDP (output) per worker (input).[/hidden-answer]

Assume there are two countries: South Korea and the United States. South Korea grows at 4% and the United States grows at 1%. For the sake of simplicity, assume they both start from the same fictional income level, $10,000. What will the incomes of the United States and South Korea be in 20 years? By how many multiples will each country’s income grow in 20 years?

[reveal-answer q="371214"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="371214"]In 20 years the United States will have an income of 10,000 × (1 + 0.01)20 = $12,201.90, and South Korea will have an income of 10,000 × (1 + 0.04)20 = $21,911.23. South Korea has grown by a multiple of 2.1 and the United States by a multiple of 1.2.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

How is GDP per capita calculated differently from labor productivity?

How do gains in labor productivity lead to gains in GDP per capita?

Critical Thinking Questions

Labor Productivity and Economic Growth outlined the logic of how increased productivity is associated with increased wages. Detail a situation where this is not the case and explain why it is not.

Change in labor productivity is one of the most watched international statistics of growth. Visit the St. Louis Federal Reserve website and find the data section (http://research.stlouisfed.org). Find international comparisons of labor productivity, listed under the FRED Economic database (Growth Rate of Total Labor Productivity), and compare two countries in the recent past. State what you think the reasons for differences in labor productivity could be.

Refer back to the

Work It Out about Comparing the Economies of Two Countries and examine the data for the two countries you chose. How are they similar? How are they different?

Problems

An economy starts off with a GDP per capita of $5,000. How large will the GDP per capita be if it grows at an annual rate of 2% for 20 years? 2% for 40 years? 4% for 40 years? 6% for 40 years?

An economy starts off with a GDP per capita of 12,000 euros. How large will the GDP per capita be if it grows at an annual rate of 3% for 10 years? 3% for 30 years? 6% for 30 years?

Say that the average worker in Canada has a productivity level of $30 per hour while the average worker in the United Kingdom has a productivity level of $25 per hour (both measured in U.S. dollars). Over the next five years, say that worker productivity in Canada grows at 1% per year while worker productivity in the UK grows 3% per year. After five years, who will have the higher productivity level, and by how much?

Say that the average worker in the U.S. economy is eight times as productive as an average worker in Mexico. If the productivity of U.S. workers grows at 2% for 25 years and the productivity of Mexico’s workers grows at 6% for 25 years, which country will have higher worker productivity at that point?

Section 7.3

Self-Check Questions

What do the growth accounting studies conclude are the determinants of growth? Which is more important, the determinants or how they are combined?

[reveal-answer q="711715"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="711715"]Capital deepening and technology are important. What seems to be more important is how they are combined.[/hidden-answer]

What policies can the government of a free-market economy implement to stimulate economic growth?

[reveal-answer q="755344"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="755344"]Government can contribute to economic growth by investing in human capital through the education system, building a strong physical infrastructure for transportation and commerce, increasing investment by lowering capital gains taxes, creating special economic zones that allow for reduced tariffs, and investing in research and development.[/hidden-answer]

List the areas where government policy can help economic growth.

[reveal-answer q="461684"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="461684"]Public education, low investment taxes, funding for infrastructure projects, special economic zones[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What is an aggregate production function?

What is capital deepening?

What do economists mean when they refer to improvements in technology?

Critical Thinking Questions

Education seems to be important for human capital deepening. As people become better educated and more knowledgeable, are there limits to how much additional benefit more education can provide? Why or why not?

Describe some of the political and social tradeoffs that might occur when a less developed country adopts a strategy to promote labor force participation and economic growth via investment in girls’ education.

Why is investing in girls’ education beneficial for growth?

How is the concept of technology, as defined with the aggregate production function, different from our everyday use of the word?

Section 7.4

Self-Check Questions

Use an example to explain why, after periods of rapid growth, a low-income country that has not caught up to a high-income country may feel poor.

[reveal-answer q="700557"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="700557"]A good way to think about this is how a runner who has fallen behind in a race feels psychologically and physically as he catches up. Playing catch-up can be more taxing than maintaining one’s position at the head of the pack.[/hidden-answer]

Would the following events usually lead to capital deepening? Why or why not?

- A weak economy in which businesses become reluctant to make long-term investments in physical capital.

- A rise in international trade.

- A trend in which many more adults participate in continuing education courses through their employers and at colleges and universities.

[reveal-answer q="640435"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="640435"]a. No. Capital deepening refers to an increase in the amount of capital per person in an economy. A decrease in investment by firms will actually cause the opposite of capital deepening (since the population will grow over time).

b. There is no direct connection between an increase in international trade and capital deepening. One could imagine particular scenarios where trade could lead to capital deepening (for example, if international capital inflows—which are the counterpart to increasing the trade deficit—lead to an increase in physical capital investment), but in general, no.

c. Yes. Capital deepening refers to an increase in either physical capital or human capital per person. Continuing education or any time of lifelong learning adds to human capital and thus creates capital deepening.[/hidden-answer]

What are the "advantages of backwardness" for economic growth?

[reveal-answer q="280514"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="280514"]The advantages of backwardness include faster growth rates because of the process of convergence, as well as the ability to adopt new technologies that were developed first in the "leader" countries. While being "backward" is not inherently a good thing, Gerschenkron stressed that there are certain advantages which aid countries trying to "catch up."[/hidden-answer]

Would you expect capital deepening to result in diminished returns? Why or why not? Would you expect improvements in technology to result in diminished returns? Why or why not?

[reveal-answer q="704888"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="704888"]Capital deepening, by definition, should lead to diminished returns because you're investing more and more but using the same methods of production, leading to the marginal productivity declining. This is shown on a production function as a movement along the curve. Improvements in technology should not lead to diminished returns because you are finding new and more efficient ways of using the same amount of capital. This can be illustrated as a shift upward of the production function curve.[/hidden-answer]

Why does productivity growth in high-income economies not slow down as it runs into diminishing returns from additional investments in physical capital and human capital? Does this show one area where the theory of diminishing returns fails to apply? Why or why not?

[reveal-answer q="461635"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="461635"]Productivity growth from new advances in technology will not slow because the new methods of production will be adopted relatively quickly and easily, at very low marginal cost. Also, countries that are seeing technology growth usually have a vast and powerful set of institutions for training workers and building better machines, which allows the maximum amount of people to benefit from the new technology. These factors have the added effect of making additional technological advances even easier for these countries.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

For a high-income economy like the United States, what aggregate production function elements are most important in bringing about growth in GDP per capita? What about a middle-income country such as Brazil? A low-income country such as Niger?

List some arguments for and against the likelihood of convergence.

Critical Thinking Questions

What sorts of policies can governments implement to encourage convergence?

As technological change makes us more sedentary and food costs increase, obesity is likely. What factors do you think may limit obesity?

Chapter 8 (now 6)

Section 8.1

Self-Check Questions

Suppose the adult population over the age of 16 is 237.8 million and the labor force is 153.9 million (of whom 139.1 million are employed). How many people are "not in the labor force?" What are the proportions of employed, unemployed and not in the labor force in the population? Hint: Proportions are percentages.

[reveal-answer q="604439"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="604439"]The population is divided into those "in the labor force" and those "not in the labor force." Thus, the number of adults not in the labor force is 237.8 – 153.9 = 83.9 million. Since the labor force is divided into employed persons and unemployed persons, the number of unemployed persons is 153.9 – 139.1 = 14.8 million. Thus, the adult population has the following proportions:

- 139.1/237.8 = 58.5% employed persons

- 14.8/237.8 = 6.2% unemployed persons

- 83.9/237.8 = 35.3% persons out of the labor force[/hidden-answer]

Using the above data, what is the unemployment rate? These data are U.S. statistics from 2010. How does it compare to the February 2015 unemployment rate computed earlier?

[reveal-answer q="83285"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="83285"]The unemployment rate is defined as the number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the labor force or 14.8/153.9 = 9.6%. This is higher than the February 2015 unemployment rate, computed earlier, of 5.5%.[/hidden-answer]

Review Questions

What is the difference between being unemployed and being out of the labor force?

How do you calculate the unemployment rate? How do you calculate the labor force participation rate?

Are all adults who do not hold jobs counted as unemployed?

If you are out of school but working part time, are you considered employed or unemployed in U.S. labor statistics? If you are a full time student and working 12 hours a week at the college cafeteria are you considered employed or not in the labor force? If you are a senior citizen who is collecting social security and a pension and working as a greeter at Wal-Mart are you considered employed or not in the labor force?

What happens to the unemployment rate when unemployed workers are reclassified as discouraged workers?

What happens to the labor force participation rate when employed individuals are reclassified as unemployed? What happens when they are reclassified as discouraged workers?

What are some of the problems with using the unemployment rate as an accurate measure of overall joblessness?

What criteria do the BLS use to count someone as employed? As unemployed?

Assess whether the following would be counted as "unemployed" in the Current Employment Statistics survey.

- A husband willingly stays home with children while his wife works.

- A manufacturing worker whose factory just closed down.

- A college student doing an unpaid summer internship.

- A retiree.

- Someone who has been out of work for two years but keeps looking for a job.

- Someone who has been out of work for two months but isn’t looking for a job.

- Someone who hates her present job and is actively looking for another one.

- Someone who decides to take a part time job because she could not find a full time position.

Critical Thinking Questions

Using the definition of the unemployment rate, is an increase in the unemployment rate necessarily a bad thing for a nation?

Is a decrease in the unemployment rate necessarily a good thing for a nation? Explain.

If many workers become discouraged from looking for jobs, explain how the number of jobs could decline but the unemployment rate could fall at the same time.

Would you expect hidden unemployment to be higher, lower, or about the same when the unemployment rate is high, say 10%, versus low, say 4%? Explain.

Problems

A country with a population of eight million adults has five million employed, 500,000 unemployed, and the rest of the adult population is out of the labor force. What’s the unemployment rate? What share of population is in the labor force? Sketch a pie chart that divides the adult population into these three groups.

Section 8.2

Self-Check Questions

Over the long term, has the U.S. unemployment rate generally trended up, trended down, or remained at basically the same level?

[reveal-answer q="401076"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="401076"]Over the long term, the U.S. unemployment rate has remained basically the same level.[/hidden-answer]

Whose unemployment rates are commonly higher in the U.S. economy:

- Whites or nonwhites?

- The young or the middle-aged?

- College graduates or high school graduates?

[reveal-answer q="261794"]Show Solution[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a="261794"]a. Nonwhites

b. The young