27.5 – Costs, Profits, and Market Structures

Learning Objectives

- Explain the equation for profits and the short run process for finding maximum profits

- List the four basic types of market structure in orthodox microeconomic theory

This chapter has laid out the basic assumptions that orthodox economists typically make about the structure of a firm’s costs, both in the short run and the long run. In the short run, diminishing marginal returns constitute the dominant assumption, creating a marginal cost curve that slopes upward as output increases as well as a U-shaped average total cost curve. In the long run, economies and diseconomies of scale are the central issue, creating a long run average cost curve that is (usually) U-shaped. By assumption, orthodox economists treat these cost structures as common to all, or at least most, businesses in the economy, regardless of the competitive conditions of their markets.

But costs are only half of the equation. Firm’s are believed to be, always and everywhere, profit maximizers in orthodox theory, where profit is:

[latex]\begin{array}{rcl}\text{Profit} & = & \text{Total revenue } - \text{Total cost} \\ & = & (\text{Price})(\text{Quantity produced}) - (\text{Average cost})(\text{Quantity produced})\end{array}[/latex]

As you’ll see over the course of the next three chapters, costs in the above equation are assumed to always have the same general relationships with quantity as discussed in this chapter. Revenue and price (which is the same as average revenue), in turn, will reflect demand in the market and the nature of competition, or market structure.

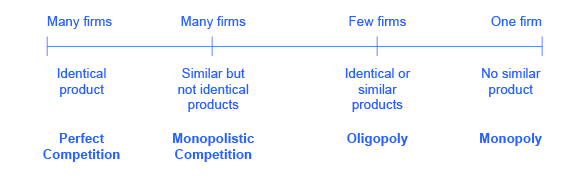

Figure 1 illustrates the range of different market structures, which we will explore in Perfect Competition, Monopoly, and Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly.

Although you will learn about this process in greater detail in the following chapters, it is worth summarizing the firm’s profit maximization decision here. Since the structure of costs and the nature of competition are generally given, the only thing the firm can really control in the profit equation above is the quantity produced. The puzzle to solve, then, becomes what quantity will generate the highest level of profit possible. The answer, for short run analysis, turns out to be very simple: profit is maximized where marginal cost (MC) is equal to marginal revenue (MR).

The reasoning behind this solution is not unlike the reasoning you saw at the end of Chapter 17, Demand and Supply. For small quantities, marginal revenue will typically be higher than marginal cost, and in this case the additional money made (MR) from producing and selling more output will be greater than the additional cost (MC) of producing it–so profit will rise. But, with higher levels of output, either marginal revenue will come down, or marginal cost will go up, or both, depending on the market structure. That is, MC and MR will converge until they’re equal, at which point there are no further profits to be made. Hence, again, profit is maximized at the quantity where MC = MR.

There is more going on in this analysis than just MC = MR, which you’ll learn in the next few chapters. For now, the above should suffice to preview that content as well as to emphasize the most core reasoning in the orthodox models of firms and market structures. It is also important to note that these models rely heavily on the assumptions about costs reviewed in this chapter.