20.4 – Micro Monetary Systems: A Comparison of Design Features

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compare different monetary systems

- Develop your own understanding of money creation and how money can be utilized to mobilize resources and create value

The previous two sections have outlined two competing narratives about money’s origin, use, and value. In this section, we explore a series of case studies to evaluate different examples of monetary system design and execution. The examples commence in settler colonial America, then progress through the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. This historical examination of money reveals a genealogical model of today’s U.S. monetary system.

Next, we take our examination international. Across the globe, communities are experimenting with monetary design. Numerous local currency experiments arise to address resource constraints akin to those faced by U.S. colonists and the Lincoln Administration identified in our historical analysis of U.S. monetary systems. However, despite circumstantial resemblance, their designs frequently reflect philosophical connections to the orthodox commodity money story. Therefore, our final case study exemplifies commodity money design. In this regard, Bitcoin provides an opportunity to contemplate the implications of digital money and the significance of the philosophical underpinnings of monetary system design.

The comparison of these monetary system case studies is framed by four questions.

- How does money enter circulation, i.e. how is it issued or created?

- Which groups have access to the currency and under what conditions?

- How much currency needs to be created?

- How do you generate acceptance or demand for your currency?

These questions and our historical analysis of monetary systems in the United States are inspired and documented by Jakob Feinig. Feinig’s (2020) Moral Economies of Money: Politics and the Monetary Constitution of Society, provides the historical context for this inquiry and represents a contemporary example of monetary analysis. As a work of monetary analysis, Feinig’s book utilizes a wide variety of data to develop new knowledge about money and monetary systems. Public records of government activity, newspaper articles, transcripts from political speeches, letters of correspondence between monetary system participants, and a host of other references, allow us to see how populations have thought about how and why money should be created and valued. Moreover, Feinig demonstrates, as Keynes’ and Marx’s theoretical models propose, that money functions as a mobilizer of resources.

Settler Colonial American Monies

The first of our case studies comes from settler colonial America. To begin building their lives in a new land, the colonists faced many challenges. One of their challenges was their status as a colony of the British Empire. A consequence of being a colony was their reliance on a global monetary system to which they had little access. Because the British Empire demanded specie money, meaning money in the form of silver or gold coins, the colonies quickly recognized the constraints to economic activity created by Keynes’s two special properties of money. First, these monies had a near zero elasticity of production, as they did not have gold and silver mines readily available to create metallic specie money (that is, gold or silver coins) demanded by Great Britain. Second, the demands by the British Empire that payments be made in specie money eliminated the possibility of substitution. As such, specie money was at the top of the hierarchy and the settlers faced a scarcity of money problem that presented many obstacles to mobilizing the resources they needed to build their communities.

To overcome the scarcity of specie money, settler colonial governments started to create their own monies. These monetary experiments were each designed to bring a wider collection of the population into the monetary economy so that resources could be mobilized and their communities could grow. Several colonial governments implemented a tax circuit to create demand and generate acceptance of their monies. Because the population understood that their local governments were creating the new monies, they understood the tax generated acceptance and was not a tool to pay for public spending or redistribute wealth. Taxes, rather, were a tool that maintained a public record of who was contributing to the production of their communities. This point was further emphasized at the end of the tax period, as colonial communities publicly burned the paper money collected in taxes. While the tax circuit was widely adopted and the issuance of new colonial monies were governance projects, the methods for controlling how much was to be issued and which groups had access were design features that varied among these monetary systems.

For example, agricultural cash crops were often used as the circulating credits. Virginia, for instance, issued certificates for quantities of tobacco stored in warehouses that circulated as money. This system of money creation promoted and advantaged tobacco production. In other cases, the use of cash crops prioritized farmers’ access to the monetary system and promoted local food production. However, paper money was more common, and a popular mechanism used to control both access and the amount created was land ownership. Land Banks allowed landowners access to credit and the ability to mobilize resources by using their land as collateral. This, of course, limited monetary access to landowners who were white males. By designing the monetary system around land ownership, the settlers alleviated the stress created by the scarcity of specie money and the British Empire for some but not all. Tobacco warehouses, cash crops, and the use of land ownership as limitations on access to credit also constrained what kinds of production was mobilized by the new money. Similar constraints remain today. Ownership and collateral are primary design elements for access to credit in today’s banking sector, and these constraints continue to generate questions about the equity of access to finance.

As the settlers became more adept at creating their own monetary systems, they innovated new design features to meet the needs of their local communities. Frequently, these designs explicitly promoted local production of goods and services. Local production and the expansion of real resources reduced reliance on specie money and also the imports that specie money often purchased. Decreasing their dependence on imports created conflict between the colonies and the British Empire. In response, the British implemented the Stamp Act, which according to the standard telling of history, generated the fervor for the American Revolution by increasing taxes on staples like tea. What this narrative generally leaves out is that the Stamp Act entered into force a context in which local money creation had been severely limited. The combination of scarcity of specie money and the restrictions on colonial money creation halted much of the colonist’s mobilization of productive resources and devastated their economies. Next, Paul Revere would ride, and George Washington would cross the Delaware, and a new country with its own monetary system would be born.

Post Revolutionary War: Banks versus Gold

The Revolutionary War ended British rule; however, the nation’s founders took from their former rulers an important monetary lesson. Rather than returning to the decentralized colonial monetary systems that had found varying degrees of success, the founding fathers restricted money creation to the newly formed federal government. This had the benefit of moving the new government’s money to the top of the monetary hierarchy, but this centralization and the elimination of local money issuance left the newly formed states without enough money to mobilize resources. To overcome these shortages, the states created bank charters, which soon enabled what become knowns as “wildcat banking”.

Bank notes became the dominant means of finance and payment in early 19th century America. This system comes with both benefits and challenges. While banks could create notes, access was again limited to those the banks found suitable. This power was one of many “unearned privileges lawmakers granted banking corporations… others included, tax acceptance of these notes, and limited liability protections.” Distrust of banks and corporate power left many seeking an alternative to this disjointed system of bank notes.

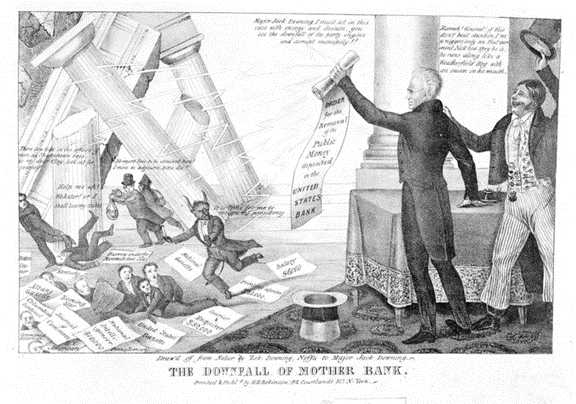

Andrew Jackson gained prominence as a critic of banks, and as an advocate for gold and silver to replace bank notes as the nation’s money. At the heart of his argument was the familiar commodity money narrative. Jackson and his followers distrusted banks and their power, and thus embraced the idea that commodity money was the only honest money. As such, Jacksonians demanded that the U.S. monetary system reject bank money and instead use gold or silver coins. They believed this would reduce money to the mere facilitator of exchanges between equal parties imagined in Locke’s origin story.

One can imagine how such stories would have political traction in the new republic. First, Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers’ writings clearly influenced many founding father’s ideas about freedom and individuality. Second, gold and silver were commonly used by banks as a means to generate acceptability of their notes. Banks would promise to convert their notes into gold or silver on demand (a very similar mechanism to using land as collateral).

However, unlike the rigorous institutional protections we enjoy in the modern era, Wild Cat banking was prone to bank failures and the inability of banks to meet their promises. The privileges granted by bank charters generated vast inequality, and significant resentment and frustrations with banks. Unfortunately, Jacksonians failed to recognize the potential of public money creation demonstrated by settler communities and tax circuits.

Instead, Jacksonians advocated for a rejection of bank credit money and the implementation of commodity money. This argument is a prototype for today’s orthodox economic models and real analysis. By obscuring the role of the state in money creation and seeking an economy based on exchange between equal parties, Jackson and his followers were advocating for the imaginary world of orthodox economics and real analysis. Without any state or financial institutions to create money, “Jacksonians began imagining a world of equal money users… a situation in which acquisitive individuals (rational agents) engaged in peer-to-peer exchanges without public or private monetary governance.” While utopian and consistent with the political economy that would give rise to orthodox economics, the forces of reality and the Civil War would quickly demonstrate the power of, and need for, the government to create money.

The Civil War and the Greenback Era

In contrast to the Jacksonian orthodox commodity money narrative, the heterodox perspective and monetary analysis presents the case that money is a social relation used to mobilize resources. One time period that provides strong evidence for the heterodox perspective is the Civil War. This period illustrates the power of public money creation, the effectiveness of a tax circuit to create demand and acceptance, the ability of the state to create access to all those who support a public mission, and the power to create as much as was needed to accomplish a goal, i.e. public money is not scarce and does not need to be found or collected as specie, taxes, or revenue.

To win the Civil War, Congress and the Lincoln Administration created the prototype for the modern monetary architecture we see today in the United States. Up until the start of the war, Congress had not fully utilized the powers outlined in the U.S. Constitution to coin money, instead relying on the Wild Cat banking system.[1] However, to mobilize the resources necessary to fight the Civil War, the North created money in four ways:

- Greenbacks were issued by the Treasury at the behest of Congress. These paper notes were declared legal tender for (almost) all debts public and private (tax circuit). Greenback issuance mobilized the Northern war effort and issuance was granted to meet the needs of the Union. The Greenback’s model of Congressional-Treasury issuance and the tax circuit are central design features of today’s dollar.

- Blackbacks were issued by a new category of federally chartered banks. By giving them a different name, it was clear that both bank money and direct fiscal spending were creatures of the state, and that bank credit creation was indeed a public responsibility. The differentiated color design feature does not exist today as bank credit is monetized and accommodated by the Federal Reserve as part of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and the finance franchise, discussed in in the previous section. This could, however, make for an interesting change in design as we move toward digital money.

- Bonds were issued by the Union. The Union promised to pay interest on these financial assets. This style of monetary instrument would be used again during WWII to discourage consumer spending and allow the mobilization of war effort-related resources through direct spending without the threat of inflation. Bonds or Treasuries serve a similar function today as part of Federal Reserve Open Market Operations.

- Certificates of indebtedness are the final monetary instrument created during the Civil War. The government used these certificates to secure resources and services to support the war effort. These certificates also circulated as cash during the war. This demonstrated to the people the power of the Federal government to issue different types of IOUs or money. What was important was the promise the state was making and what the currencies were being created to achieve.

Together, these four types of monetary instruments helped mobilize the labor and capital necessary for the United States to abolish slavery and remain a union. War efforts are often times of monetary experimentation. The Second World War and the New Deal also saw the expansion of Federal agencies and the creation of new monetary instruments. Unfortunately, in both cases, the ability of the federal government to create money was quickly obfuscated, during the transition to peacetime, by narratives centered around commodity money. These stories have the effect of limiting the public’s imagination about where money comes from and how it works. Jakob Feinig defines these practices as monetary silencing. Therefore, it is critical to approach monetary systems using the four questions above to avoid being silenced. We might not need to fight a Civil War or defeat Nazis, but there are other challenges for which large-scale monetary mobilization of resources might be the solution. The climate emergency, the border crisis, poverty and homelessness are some that might come to mind.

Local Currency Systems and Community Currencies

While Greenback experimentation drew on lessons about the importance of tax circuits and the power of the public to mobilize needed resources, much of today’s experimentation draws on the commodity money and real analysis framework to address problems created by scarcity of monies that sit on the top of global hierarchies.

Local currency systems (LCS) or community currencies are a growing phenomenon. Just as settler colonial America had many different designs for their different monies, LCS vary greatly. This variance and prevalence is evidenced by the emergence of an academic journal dedicated to the study of such systems. The International Journal of Community Currency Research features articles by scholars in economics, history, geography, law, sociology, anthropology, and political science, etc. The strength of these interdisciplinary perspectives is that it offers many different techniques for analyzing monetary system designs.

One reason that such a diverse set of tools is necessary for studying community currencies is that if the Metalist’s story of money is false, then the price mechanism or the invisible hand is not an adequate means of determining value. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde tells us that; “Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” Community currencies are projects that allow communities to assign values to activities and goods that central currency schemes are not valuing. Accordingly, LCS attempt to increase access to money to help their communities mobilize resources. These systems increase access by altering the conditions from which money is created, and demonstrate that money scarcity prevents valuable work from being done.

As such, LCS, like settler colonial monies, represent small scale experiments from which we can gain meaningful knowledge about various money design features. Additionally, scholars have uncovered general philosophies that influence the creation of these systems. Common philosophical underpinnings include solidarity and reciprocity. The philosophical grounding of these systems influences the goals and the purpose of currency creation. Examples include: community stability, intergenerational relationship building, and strengthening territory or stimulating economic activity. From these general goals, communities create real jobs: to promote sustainable production, support the elderly, deliver women’s programs, and other civically oriented tasks not being met by the market of fiscal sectors of the economy.[2] Thus, when value is reintroduced into a discussion about the economy, the limited tool set available under real analysis is replaced by a diversity of methodologies from several academic disciplines.

In an effort to organize the analysis of this diverse and growing collection of money systems many scholars sort them into three categories.[3] The first category is territorial projects. These projects are typically defined by geographic boundaries and are designed to strengthen the area’s resilience and foster new development. The second category is community projects. These are implemented to address a specific community need. Such needs are usually determined by a group of local actors attempting to emphasize increased wellbeing, empowerment of a repressed group, or support environmental health. The third category is a complementary currency. Complementary currencies are designed to support an economic objective. These systems are generally designed with regard to market principles and work to support activities between production and exchange of goods and services. While each of these categories has their own unique details, these categories are not mutually exclusive in their characteristics. In fact, many take on objectives and characteristics that draw from multiple categories. One such currency system is the Red del Traque (RT) of Argentina.

Ecologists developed the RT currency system. In this ecological model, the wellbeing of women and families were a primary objective. To support the wellbeing of women and families, markets or ‘nodos’ were set up in economically depressed neighborhoods. These markets used the RT currency system to organize labor efforts and create household stability by encouraging self production, reducing waste, promoting resale of household items, providing social welfare labor, and helping to distribute unsold surpluses in local businesses through new trade outlets.[4] Thus, from this description we could classify the RT in all three of the suggested category types. It is a community currency based on its primary objective. It can also be described as a complementary currency as it facilitated market exchanges, and it targeted particular territories based on economic need.

By creating a local currency system, many Argentinians who had been abandoned by the peso economy were provided an opportunity to contribute to social activity and find some economic stability. The RT changed how money was issued and increased access, but one design feature that makes the RT different from the experiments in the U.S. is the lack of a tax circuit. The RT, like many LCS rely on a convertibility model for generating demand and acceptability. Rather than converting their created currency into gold, they often promise to convert it into the national currency or U.S. dollars. This method creates trust, but significantly limits their power to create new money.

A second feature that limits many of these systems is their emphasis on consumption, rather than generating new production. The RT for example, creates markets for exchange. Emphasis on exchange and consumption limit their ability to realize the philosophical goals of solidarity and trust. This is evidenced by these systems’ volatile nature. Often, these systems fold as soon as participants are able to secure enough of the national currency to no longer need to participate in the LCS.

Similar challenges exist for potentially the most famous complementary currency, Bitcoin. We will now turn to digital money and Bitcoin’s design.

Bitcoin and Digital Money

Bitcoin is probably the most well recognized of the monetary experiments we’ve discussed so far. This recognition is likely driven by its existence as code and a digital monetary experiment. As code, Bitcoin’s design is more obvious than it might appear for the other monetary systems. The protocols that are executed to create new Bitcoins were written by the anonymous programmer known only by the handle Satoshi Nakamato.[5]

Like Bitcoin’s founder, the creation of new blocks on the blockchain are also anonymous. Decentralized programmers mine new Bitcoin by solving complex mathematical algorithms. This design feature for creation of Bitcoin is energy intensive. Mining requires abundant electricity and computing power, but it does not require the social energy of trust or institutional hierarchy. As Nakamoto explains in the Bitcoin white paper,

What is needed is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two parties to transact directly without the need for a trusted third party.

Nakamato’s digital peer-to-peer direct facilitator of transactions is thus designed to model electronically the Metallist story of money, all the way down to its “mining.”

Just like the Jacksonians, Bitcoin romanticizes the imagined unmediated exchanges of equal parties in the orthodox model and real analysis. In the real analysis model, recall, money is neutral. Money does not influence productive activity, it is only the facilitator of exchanges.

Bitcoin’s code also models other important features of the orthodox story. Bitcoin is theoretically stateless. Issuance is generated by decentralized actions of programmers, not a centralized state. This feature also means that it does not have a tax circuit. Without this design feature to generate demand it relies on the orthodox assumption of scarcity to generate value and demand. Scarcity is written into the code. A final Bitcoin will one day be mined.

Is the experiment generating the desired results? Is Bitcoin overcoming state hierarchies and global currency systems like the dollar? The short answer is no. Rather than replacing institutions like the Federal Reserve and the financial sector, Bitcoin is being absorbed by the existing system, not as a currency, but as a speculative investment security.

Bitcoin worked early on. People used it to buy coffees in Seattle and conduct everyday transactions, but as it worked, it became valuable as an exciting new technology. As a consequence, rather than continuing to use it in peer-to-peer transactions, people collected them and stored them with the hope that the price would continue to rise. This is interesting, because Bitcoin’s price or value is articulated in an existing state money, i.e. this Bitcoin could be worth $50,000 or $1 depending on market fluctuations. This means that someone must be willing to buy your Bitcoin for that price for it to have that value.

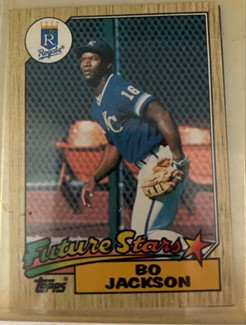

This makes Bitcoins more like a baseball card collection than an emerging monetary system. I used to love collecting baseball cards and looking through the pricing catalogs to see how much my Bo Jackson and Mark McGuire rookie cards were worth. They are going to be worth thousands of dollars, my friends and I would joyfully claim. The longer we hold on to them the more they will be worth. Sadly, the market for baseball cards was not what we imagined, and while Bitcoin’s cryptographic technology has some promise as a design feature for future digital monies, it does not appear that its value will ever be as a monetary system that facilitates trade. It has become a speculative asset, just like a baseball card or piece of art.

But, the Bitcoin experiment is instructive. It demonstrates the importance of the tax circuit and the power of reciprocal promises to give money value, but not so much value that it does not circulate. Bitcoin also shines a light on the importance and value of trust. While we might not all agree on the politics of how state money is being created, or what the financial sector is crediting, the hierarchy and the promise of redemption and the guarantees promised from the top create stability in our lives. Moreover, Bitcoin demonstrates that money is an experiment and that, like Hyman Minsky said, “anyone can create it, the trick is getting others to accept it.” This too boils down to trust. If money is a social relation and a promise to pay, then how might we write new code, laws, and promises to improve our lives?

Classroom Currencies

One way to test Minsky’s hypothesis is to design and implement your own monetary system. This can be done as a classroom experiment. This experiment is modeled to test the design features posited by Modern Monetary Theory. Execution of the experiment is completed in four simple steps.

- First, the instructor is the issuer of the new money. As the issuer, the instructor can create their own paper money. The creation process can add students through an invitation to name and develop the art for the paper money.

- The class then decides what resources need to be mobilized. One straightforward way of doing this is promising to pay students for hours volunteered at local not-for-profits. This provides support to those institutions, while giving students valuable service learning experiences. These experiences are well complemented by reflection writings that allow time to ponder why valuable services like feeding the hungry are so reliant on volunteers.

- To create demand and receivability for the currency, the issuer must levy a tax. At the end of the semester, the tax is due, and only after payment is made in the classroom currency are the points for the assignment awarded. This is the primary reason for the instructor issuing the currency. How much power does the instructor want to wield? The tax provides lots of room for experimentation. How large does the tax need to be to motivate work and production? This also raises theoretical questions about the hierarchy of money. For example, is this relationship coercive? Are there other designs that generate demand? Would it be possible for students to issue the currency? What could they promise to redeem?

- Have fun with it! Do students who collect more of the currency, because they really enjoy their volunteer work, begin using the currency with students who are not collecting enough to pay the tax? What can your classroom currency buy? How much work is mobilized. Should this type of work be financed in dollars and not left to volunteers? Can you spread the use of your currency across semesters or other classes and departments? As we have seen, money is interdisciplinary.

To conclude and summarize, money takes on very different roles in our economic system. Often these roles and our perspective of what money can and cannot do are based on the methodology applied to study economic activity. If money is simply the medium of exchange, then the coordination of inputs to produce outputs is the role of individual firms and money is neutral and scarce. However, when money is studied from the perspective of historical and institutional settings, business enterprises need money to initiate those coordinating functions, as we theorized in Marx’s circuit of money capital and Keynes’s monetary production economy. Given this central role in all economic activity, the task of economists and other scholars is to help society create laws and institutions such that money is available to initiate productive value generating work and effort. You can be part of that process! So use your knowledge to contribute to money’s design and make an impact in people’s lives!

Discussion Questions

Based on the categories of local currency systems you’ve learned about, how would you classify the Greenback or Land Bank notes?

How would you model Bitcoin using Keynes’ own rate?

- See Article 1, Section 8. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript ↵

- This information can be found in “Community currency research: An analysis of the literature” in Vol. 15 in the 2011 International Journal of Community Currency. ↵

- The French economist Jerome Blanc has published widely in the area of community and complementary currencies. ↵

- Georgina Gomez and Bert Helmsing from the Hague in the Netherlands published a very interesting article about the spatial distribution of the RT in Argentina in the 2008 Vol. 36(11) of World Development titled “Selective Spatial Closure and Local Economic Development.” ↵

- See https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. ↵

coins created from precious metal such as gold or silver