14.7 – Price Cyclicality, Post-1983

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to

- Explain, using heterodox economic theory, the underlying causes for acyclical prices beginning in the early 1980s

Beginning in the early- to mid-1980s, the cyclicality of prices began to change in the U.S. Whereas, for several decades previously, the price level tended to go up faster in recessions than expansions, prices began to become detached from the business cycle altogether. That is, inflation became acyclical (neither procyclical nor countercyclical).

In a 2015 article in Metroeconomica, economist Gyun Gu looked at the manufacturing sector to explain this change. He found that two socio-economic changes were at the heart of the matter. First, businesses began responding more promptly to increases and decreases in the costs of labor and materials, increasing or decreasing their prices to pass the cost changes along to their customers. These sorts of pricing responses used to occur more gradually, so as they began to occur more rapidly the resulting ups and downs of prices happened over shorter periods–years or even months, rather than the usual 5-7 years of the business cycle. Instead, the net impact of the more-frequent price adjustments could be positive, negative, or nil–hence, acyclical prices.

The second reason that price countercyclicality has moved to price acyclicality has to do with a topic we covered earlier in this chapter: labor power. The 1980s saw the beginning of a long decline in the negotiating strength workers have relative to their employers. Declines in union membership and increasingly hostile public policy toward collective bargaining, coupled with the gradual erosion of the social safety net, meant that workers were more dependent on their employers for a livelihood and less able to demand better working conditions, higher pay, and so on.

In this context an increase in unemployment creates a labor disciplining effect, in which the threat of further layoffs impels workers to work harder, to produce more, and often to take up the slack of their recently terminated coworkers. The effect on the business’ income statement is to produce steady output with a smaller number of workers. Economists would call this an increase in labor productivity (output per worker or hour of work), and since the labor disciplining effect suggests that productivity increases in a recession (higher unemployment), we must be talking about countercyclical labor productivity in this context–the opposite of the labor hoarding effect.

But to businesses, the increased productivity looks like decreased labor costs per unit as output declines–and vice versa: higher unit labor costs with higher output. To be sure, we’re painting in broad strokes here, and the labor hoarding effect still exists as well, so unit labor costs surely don’t increase as output increases and vice versa for all modern businesses. Just the same, the increasing dominance of the labor disciplining effect since the 1980s is yet another factor alleviating the countercyclical pressure on costs and therefore prices.

Finally, a note on the economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. This chapter was last updated about two years after the beginning of that pandemic in the U.S. As you may have heard, the economic impact was significant, with supply-chain disruptions, extraordinary economic policy measures, temporary shutdowns (which for many businesses, became permanent), and so on. In terms of prices, the pandemic marked the end of roughly three decades of relatively stable prices.

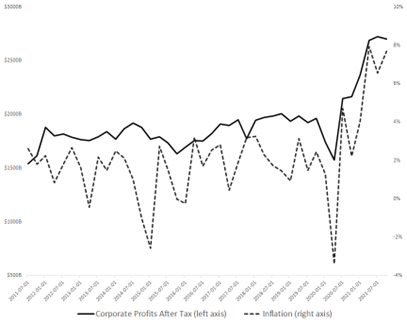

As Figure 1 above shows, the beginning of the pandemic (spring of 2020) saw a sharp decline in prices while corporate profits took a hit as well. Prices quickly rebounded, however, as did corporate profits, which appear to have been a significant driver of the ensuing inflationary period. Will the inflation subside as many economists initially predicted, or will it continue for a longer period, perhaps even leading to a new era of stagflation? What are the main causes of the inflation and what can be done to bring it down?

It’s too early to answer these questions, especially in a textbook, but economists are sure to develop explanations, including those that utilize the heterodox perspective. Who knows? Perhaps the future economist that best explains the pandemic inflation will be you!

References

Gu, Gyun Cheol. 2015. “Why have U.S. prices become independent of business cycles?” Metroeconomica 66(4): 2015.

Glossary

- labor disciplining effect

- the effect of job cuts in causing workers to work harder, to produce more, and often to take up the slack of their recently terminated coworkers

the effect of job cuts in causing workers to work harder, to produce more, and often to take up the slack of their recently terminated coworkers