20.3 – Money and the Macroeconomy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Apply the vocabulary and conceptual framework developed in the previous section to the Hierarchy of Money

- Explain money’s social origin in a monetary production economy

The Money Hierarchy and the False Duality of the State and Market

Hyman Minsky once argued that anyone can create money; the real trick is getting people to accept it.[1] What Minsky is pointing out here is that money, as a social relation, is a promise or an IOU. IOUs are useful social instruments that allow us to connect the present with the future. For example, if I take a beverage from the refrigerator, today, that belongs to one of my roommates, I might leave a note that says IOU a soda. That note is now an asset, or the promise of a delivered soda in the future. In addition to creating an asset, I have also created a liability or debt in the form of the future delivery of that soda.

What we demonstrate in this section is that all money is an IOU or two-sided balance sheet operation. Money is always an asset and a liability. So while I might be able to create all kinds of IOUs, if I break those promises and their status as assets comes into question (the certainty that the note will one day be redeemed for a soda), then my roommate might invest in a lock for his sodas and refuse to accept my IOUs. Thus, we want to explore the “trick”. Why do people accept IOUs of any type, whether they are promises from friends or the IOUs of the United States – Federal Reserve Notes, aka dollar bills?

This inquiry will again take us away from the orthodox narrative. As a reminder, from their perspective gold or a precious metal’s intrinsic value ensured money’s acceptance as a facilitator of exchange and reduced the transaction costs of a barter economy by solving the double coincidence of wants. This simple narrative sheds money of its social character and reduces it to a neutral commodity making real analysis possible. In the orthodox story, money emerges as a market phenomenon. One of the consequences of this plot line that we would like to consider is the adversarial or dual relationship between the state/government and the market it animates.

Under the terms of the orthodox origin story, we think of the market and the state as opposing forces struggling to direct economic activity. Given this orthodox framing, one might imagine the market as the strong lead character in pursuit of efficient solutions, and the state as a pesky nemesis taking resources from the market to achieve its own nefarious and often overly bureaucratic agendas. This plot, however, takes an unexpected twist in Modern Monetary Theory, as these two characters are revealed to be one and the same, or at least inseparable. The orthodox real analysis claims of duality between the state and the market are revealed to be nothing more than the byproduct of their methodology. The “trick” is not that we accept dollars, but that the true source of their value continues to be largely ignored by economists, policymakers, and the general public.

In 2011, renowned London School of Economics anthropologist, the late David Graeber published a comprehensive examination of the historical origins and development of money, titled Debt: The First 5,000 Years. While all 5,000 years are interesting, and students are encouraged to explore this detailed work of scholarship, our focus will be on the current economic system. This focus will allow us to build upon the above ideas of Smith, Marx and Keynes and to develop an understanding of key concepts from Modern Monetary Theory. The first of these concepts is the hierarchy of money. From this conceptual framework, we will explore the technostructure of money. The collection of institutions that regulate money’s issuance or production are similar to the market governance of business enterprises in that stability is a primary objective (see chapter “The Megacorp”). Given the central role of money in economic activity and its origins with the state, the clear delineation between where the market begins and the state ends is all but erased.

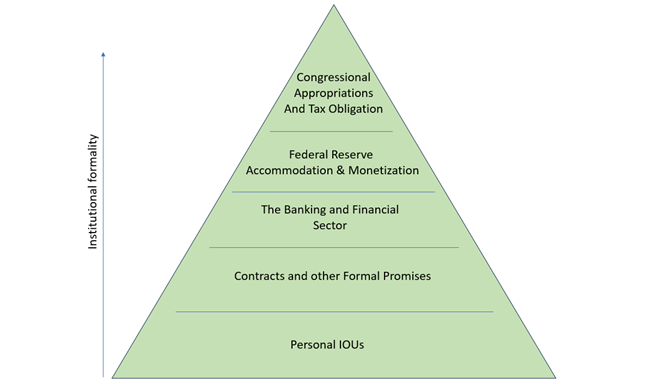

We begin our monetary analysis with the hierarchy of money. My promises to deliver a future soda and U.S. Federal Reserve Notes aka dollars are clearly not equally accepted or received. The hierarchy of money is an analytical framework that helps differentiate IOUs. Figure two provides a visual demonstration of the hierarchy’s technostructure. At the base of the hierarchy are all the informal IOUs we might create. What differentiates these common and largely unregulated IOU transactions from those that are described as we move up the hierarchy is the institutional formality and enforceability of those social relations.

So the second level, contracts and other legally formalized promises, might be promises to pay businesses, such as your network service provider. They promise to provide a service for a year, and you promise to pay a dollar amount for that service. They credit you with service and you pay back your debt. This contract, unlike my note in the refrigerator, is legally enforceable in dollars. If you or the network provider breaks your promise legal recourse is available.

Moving on up the hierarchy we have the financial sector, the U.S. Federal Reserve, and then U.S. Congress at the very top. The formality and institutional structure of the social relations are what places these institutions at higher levels of this hierarchy. As one goes up the hierarchy the formality helps to increase the receivability or acceptability of those institutions’ IOUs. U.S. dollars have the highest degree of receivability, as the number of items for sale in U.S. dollars is extraordinarily large. In contrast if you write an IOU for lunch, there are likely only a small number of people that would be willing to accept your note.

Near the top of the hierarchy, the financial sector and the Federal Reserve are connected by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. This relationship will be discussed below in great detail in the Finance Franchise section. Therefore, we will jump to the top of the hierarchy and discuss Congress and the Federal Government. Congress is unique, because by Constitutional law it is the sole source of new U.S. dollar creation. This institutional reality is one of the most significant aspects of Modern Monetary Theory, because in stark contrast to the Metallist’s story, money comes from the state, not the market.

Figure 2 displays the hierarchy in action. Observe, when the red line goes into the negative (government deficit), the black line increases (private sector wealth). This increase is nearly 1:1 ratio. The relationship between public and private spending is described by the accounting identity equation known as sectoral balances:

[latex]0 = (S - I) + (T - G) + (\text{net exports})[/latex]

This accounting identity and equation states that the balance sheets of the private, public, and international current accounts sectors of the economy sum to zero. Meaning, if we were to close the economy and only have the public and private sector, then when the private sector spends more than it takes in (deficit spends), the public sector, by accounting identity, runs a surplus. This situation rarely occurs. However, if we examine Figure 2 closely, we see that in the early 2000’s there was a very brief period of government budget surpluses, only to be followed by recession and a swift movement back to state deficits and private surpluses.

Before pressing forward, let’s take a moment to summarize the hierarchy of money. Money is a social relation. It is a two-sided balance sheet operation or an IOU. It consists of at least two parties who agree to a credit-debit relationship. The hierarchy of money is characterized by the institutional constraints and enforcement of these social relations. At the top of the hierarchy is the issuer of the currency. The currency issued in the United States is the dollar. Rather than the dollar emerging in the market to solve the double coincidence of wants, the dollar is legally created by the state. So now that we have a definition and have identified where money comes from, we are left with the question of value. If there is not a precious metal or intrinsic value to the dollar, then where does its value come from?

Value comes from a promise extended by the state to accept U.S. dollars as payment for taxes and other obligations, such as fees and fines. This promise creates demand for dollars in the United States and beyond. This demand for dollars is what maintains the dollar’s value–i.e., what makes it so widely receivable. Therefore, Modern Monetary Theory argues that taxes drive money. The tax circuit and the dollar’s guaranteed receivability to clear your liability with the public is a design attribute of the monetary system. This design feature makes the dollar receivable for a great many goods and services. If, on the other hand, the dollar was not issued by the state, but followed the logic of the barter story, why would any of us accept dollars–maybe faith? We will examine this question more closely in the next section through the lens of crypto currency.

Before we move on to crypto and identify its design features, it is useful to stick with the dollar and take a closer look at the sources of dollar creation and how that relates to the provisioning of dollars and value theory. To do so, we pose a provocation. How does our perspective of what has value change when we approach money as an industry with the United States as the monopoly producer of dollars? Is this monopolist structure leading to effective coordination of labor and capital in our economy? Could a different technostructure of money deliver better outcomes?

The Dollar Monopolist and its Finance Franchise

As the monopoly producer of the dollar, the United States government is not the pesky nemesis taking money from the market to fund its spending. Instead, it is the source of new dollar creation through Congressional appropriations. You and your families may have experienced this directly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Congress signed a number of bills into law, including the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. For many, this Act appropriated new money that was either directly deposited into your bank accounts or a check was issued and mailed to you from the U.S. Treasury. The CARES Act initiated millions of balance sheet operations and in that process, it increased the dollar holdings of millions of Americans. At the same time, the CARES Act also created the corresponding debit of the Government’s balance sheet.

There are a couple of items worth noting about these transactions. First, the spending increased the amount of money Americans had in their accounts. This is the black line shooting up into the positive in the sectoral balances accounting identity in Figure 2 above. Second, this spending was not “funded” by taxes or government borrowing. These dollars were created by Congress through votes. In doing so, it drove the balance sheet of the public government sector negative, the red line in Figure 2. This is deficit spending. Deficit spending takes place when the government spends more money into the economy than it takes back at the end of the year in taxes. The sum of all the times the U.S. government deficit spends is the national debt.

As the monopoly issuer, the federal government uses fiscal policy—legislation passed by Congress and signed into law by the President to mobilize resources. The CARES Act allowed many people to remain at home and avoid spreading COVID-19, while also keeping businesses and public enterprises from going out of business during the shutdown period. While we can debate the merits and effectiveness of this Trump Administration legislation, the money to execute the law did in fact coordinate a great deal of economic activity. Similar to military appropriations, the relief money for families was spent and there was no corresponding obligation to pay the monies back. This is one of the unique powers of public spending.

However, this direct state appropriation of money into our bank accounts is not how many of us experience new money creation on a day-to-day basis. It is a relatively rare occurrence that the Federal government just sends money directly to everyone, and Congressional legislation does not mobilize all of our economic activity, so how is it that the rest of the economy gets the money it needs to coordinate and mobilize resources? The answer is the U.S. government has created a franchise partner to facilitate dollar creation.

You are probably familiar with the franchise concept. Many retail chains, such as McDonalds, Ace Hardware, Seven Eleven, and UPS Stores are all well recognized brands and successful franchises. Merriam-Webster defines the franchise as: “the right or license granted to an individual or group to market a company’s goods or services in a particular territory or a constitutional or statutory right or privilege.” The franchise of the U.S. government or the statutory rights and privileges to create U.S. dollars are granted in the form of bank charters. Bank charters provide banks with the legal authority they need to create financial instruments denominated in dollars.

So just like Congress, the new money created by banks does not come from some pre-existing pile of dollars, but is generated from thin air. The same could be said about any promise I make or you make in order to mobilize activity. The difference between promises made by the state, banks, businesses, and you and I are the institutional and legal structures that back those promises. As we saw above, this is what organizes money’s hierarchical technostructure and its value. While these institutional legal structures may vary substantially, at the end of the day they are all social relations.

This definition of money again creates significant differences between heterodox and orthodox economic scholars. To maintain the commodity money framework and the assumed barter system for real analysis, orthodox scholars model banks as intermediaries. Similar to assuming that commodity money simply facilitates trade between willing parties in barter transactions, banks provide the service of connecting savers and investors. In other words, they operate as intermediaries between those who want to save their money and those who are seeking money in order to invest. Thus, just as commodity money is a neutral actor that does not influence economic activity, banks are neutral actors that match savers and borrowers, and the price that “clears” the loanable funds market and all this intermediation is the interest rate (see section “The Building Blocks of Neoclassical Analysis“).

Regardless of your view of banks, it is difficult to defend the idea that they are nothing more than neutral intermediaries. Just like money, banks are more than simple facilitators of exchange. In addition to the non-neutrality of banks, another significant problem with the orthodox loanable funds model of bank activity is that interest rates are not determined by market forces, but are a policy variable. The Federal Reserve sets and maintains the Fed Funds interest rate. This interest rate guides decisions about the formulation of all other interest rates in the economy. The price, in other words, is determined by the Fed, not markets.

It is from the Fed’s announced rate that banks evaluate and decide what activities are likely to generate returns. If the bank decides that the returns from a new deal are adequate, then the money needed to execute the deal is created. Here is an example. If you want to start a cheeseburger stand and need $50,000, the bank will assess your business plan and the likelihood that you will be able to sell enough cheeseburgers to manage your loan. If it approves your loan, it does not need to see if enough deposits have been made by savers to award you the $50,000; it will simply have you sign a promissory note, credit your bank account (create new deposit), and keep the note as an asset that will pay the bank the principal amount of the loan and an agreed upon rate of return. Thus, one of the primary claims of Modern Monetary Theory is that money is endogenous: loans create deposits. Banks are creators of money, not intermediators. (For more information on this process, including an illustrative example, see section “How Banks Create Money”.)

Therefore, the mobilization of a significant amount of economic activity is generated by the federal government’s banking franchises. This means that the financial industry plays a supporting role to the state in value creation and decisions about what kinds of economic activity should be mobilized by money creation. This monopoly structure of our economy that combines Congressional appropriation and direct money creation, with a collection of finance franchises that make decisions about money creation based on their profitability is the most recent iteration of 5,000 years of debt. What this 5,000 years reveal is that there is nothing inevitable about this system. Rather, the existing legal and institutional structures that organize money’s creation are all experimental and subject to change.

If money’s design and institutional organization is malleable, what might alternative designs look like? Many MMT theorists argue that the values of the community would be better met through a universal program for full employment.

A Jobs Guarantee program would change how much money is created, expand the purpose of its creation, and diversify who has access to money creation. Other scholars have called for replicating and expanding the scope of banking charters to allow for the creation of more public banks, while Silicon Valley and technologists argue for the digital transformation of our monetary systems.

Regardless of the design changes that take place, the sectoral balances relationship between the public and private sector, as well as the franchise arrangement, suggest that there is an intimate relationship between state and market activities. The approach taken by orthodox economics, on the other hand,describes an antagonistic relationship based on real analysis, because the state must take money from the private sector to spend. The history of money creation and an institutional analysis of the monetary system’s technostructure debunks this description of money as a commodity. If, as Keynes suggests, we live in a monetary production economy and all new money creation comes directly or indirectly from state appropriation and legal charters, then continuing to approach the market and state as hard duals is likely to be problematic. This leads us to ask, how might we diversify and democratize money creation in new and creative ways moving forward?

To further examine money’s ability to mobilize resources and create value, we will now turn to an examination of U.S. monetary history, international local currency systems, and digital money. By looking at these more “micro” monetary systems, we can improve our understanding of the existing “macro” monopoly money system’s strengths and weaknesses. Using this knowledge we then hypothesize how we might change the design of money to enhance our ability to coordinate and mobilize our resources. We will conclude by modeling and describing how you can conduct your own monetary experiments in your classroom and community.

- Stephanie [Bell] Kelton’s 2001 Cambridge Journal of Economics article “The Role of the State and the Hierarchy of Money” is widely considered to be a seminal piece in the development of Modern Money Theory. ↵

the study of real changes to output, employment, distribution, and growth without addressing money as anything other than a facilitator of exchange

the rules and practices defining how business enterprises will behave in a market, including especially how they will interact with their competitors