11.3 – Orthodox Economics and The Neoclassical (New-Keynesian) Synthesis

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the relationship between sticky wages, prices, and employment using various economic arguments

- Explain the coordination argument, menu costs, and macroeconomic externality

- Explain the Phillips curve, noting its impact on the theories of new-Keynesian economics

- Graph a Phillips curve

- Identify factors that cause the instability of the Phillips curve

- Analyze the new-Keynesian policy for reducing unemployment and inflation

While Keynes’ own work, especially in the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, is considered revolutionary in the world of economics, many of its insights are obscured by an orthodox reading of his text. Orthodox readings and interpretations produced what has variously called New-Keynesianism, the Keynesian or Neoclassical Synthesis, or, as economist and colleague of Keynes himself, Joan Robinson called it, Bastard Keynesianism. From the orthodox perspective, Keynesian economics is not about a fundamentally different way of understanding capitalist economies. Instead, this brand of Keynesian economics (referred to here as New-Keynesian economics), is simply an approach within orthodox economics that focuses on explaining why recessions and depressions occur and offering a policy prescription for minimizing their effects. In particular, the New-Keynesian view of recession is based on the fundamental insight that aggregate demand simply is not always automatically high enough to provide firms with an incentive to hire enough workers to reach full employment.

The first building block of this New-Keynesian diagnosis is that recessions occur when the level of demand for goods and services is less than what is produced when labor is fully employed. In other words, the intersection of aggregate supply and aggregate demand occurs at a level of output less than the level of GDP consistent with full employment. Suppose the stock market crashes, as in 1929, or suppose the housing market collapses, as in 2008. In either case, household wealth will decline, and decreases in consumption expenditure will follow. Suppose businesses see that consumer spending is falling. That will reduce expectations of the profitability of investment, so businesses will decrease investment expenditure.

This seemed to be the case during the Great Depression, since the physical capacity of the economy to supply goods did not alter much. No flood or earthquake or other natural disaster ruined factories in 1929 or 1930. No outbreak of disease decimated the ranks of workers. No key input price, like the price of oil, soared on world markets. The U.S. economy in 1933 had just about the same factories, workers, and state of technology as it had had four years earlier in 1929—and yet the economy had shrunk dramatically. This process of decline relating to markets, consumption, and investment decisions also seems to be what happened in 2008.

Keynes’s understanding and description of the events of the Great Depression contradictsSay’s law where “supply creates its own demand.” Although production capacity existed, the markets were not able to sell their products. As a result, real GDP was less than potential GDP. One of the provocations raised by Keynes in the General Theory is if economic adjustment, particularly in labor markets, from a recession back to potential GDP, takes a very long time, then neoclassical theory is more hypothetical than practical. In response to John Maynard Keynes‘ immortal words, “In the long run we are all dead,” neoclassical economists argued that even if the adjustment takes as long as, say, ten years, the neoclassical perspective remains of central importance in understanding the economy. For orthodox economics, the question becomes, then, how can Keynes’ ideas be reconciled within orthodox economics in which Say’s law still holds? There are a number of answers to this question, but one important one is: wages and prices don’t adjust appropriately, at least not quickly.

Wages and Price Stickiness

One essential way in which Keynes’ arguments were ‘bastardized’ and synthesized into neoclassical economics was simply to ignore his observations on the impact of wage and price cuts in recessions. As will be discussed in the Heterodox Macroeconomic Perspectives Chapter, while Keynes had noted what would be obvious to most as it concerned wages and unemployment–namely, that wage cuts in a recession would likely decrease sales and therefore increase unemployment–many orthodox economists reread this as simply an observation that prices and wages don’t immediately respond as economists often expected. As a result, orthodox economists began to consider whether prices and wages could be “sticky,” making it difficult to move a less than fully employed economy toward full employment and potential GDP. Stated differently, orthodox economists argue that a drop in wages decreases unemployment. However, a problem ensues if wages do not drop when there is unemployment. Absent a wage reduction the economy finds itself stuck in a less than full employment scenario.

Why Wages Might Be Sticky Downward

If a labor market model with flexible wages does not describe unemployment very well—because it predicts that anyone willing to work at the going wage can always find a job—then New-Keynesian economics suggests that it may prove useful to consider economic models in which wages are not flexible or adjust only very slowly. One set of ad hoc reasons New-Keynesians argue that wages may be “sticky downward,” involves economic laws and institutions. For low-skilled workers receiving minimum wage, it is illegal to reduce their wages. For union workers operating under a multiyear contract with a company, wage cuts might violate the contract and create a labor dispute or a strike. However, minimum wages and union contracts are not a sufficient reason why wages would be sticky downward for the U.S. economy as a whole. After all, out of the 165 million or so employed workers in the U.S. economy, 98% are paid more than the standard federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. Similarly, labor unions represent only about 11% of American wage and salary workers (an 83 year low). In other high-income countries, more workers may have their wages determined by unions or the minimum wage may be set at a level that applies to a larger share of workers. However, for the United States, these two factors combined affect only about one in eight workers.

Economists looking for reasons why wages might be sticky have focused on factors that may characterize most labor relationships in the economy, not just a few. Many have proposed a number of different theories, but they share a common tone.

One argument is that even employees who are not union members often work under an implicit contract, which is that the employer will try to keep wages from falling when the economy is weak or the business is having trouble , and the employee will not expect huge salary increases when the economy or the business is strong. This wage-setting behavior acts like a form of insurance: the employee has some protection against wage declines in bad times, but pays for that protection with lower wages in good times. Clearly, this sort of implicit contract means that firms will be hesitant to cut wages, lest workers feel betrayed and work less hard or even leave the firm.

Efficiency wage theory argues that workers’ productivity depends on their pay, and so employers will often find it worthwhile to pay their employees somewhat more than market conditions might dictate. One reason is that employees who receive better pay than others will be more productive because they recognize that if they were to lose their current jobs, they would suffer a decline in salary. As a result, they are motivated to work harder and to stay with the current employer. In addition, employers know that it is costly and time-consuming to hire and train new employees, so they would prefer to pay workers a little extra now rather than to lose them and have to hire and train new workers. Thus, by avoiding wage cuts, the employer minimizes costs of training and hiring new workers, and reaps the benefits of well-motivated employees.

The adverse selection of wage cuts argument points out that if an employer reacts to poor business conditions by reducing wages for all workers, then the best workers, those with the best employment alternatives at other firms, are the most likely to leave. The least attractive workers, with fewer employment alternatives, are more likely to stay. Consequently, firms are more likely to choose which workers should depart, through layoffs and firings, rather than trimming wages across the board. Sometimes companies that are experiencing difficult times can persuade workers to take a pay cut for the short term, and still retain most of the firm’s workers. However, it is far more typical for companies to lay off some workers, rather than to cut wages for everyone.

The insider-outsider model of the labor force, in simple terms, argues that those already working for firms are “insiders,” while new employees, at least for a time, are “outsiders.” A firm depends on its insiders to keep the organization running smoothly, to be familiar with routine procedures, and to train new employees. However, cutting wages will alienate the insiders and damage the firm’s productivity and prospects.

Finally, the [add glossary term]relative wage coordination argument[end glossary] points out that even if most workers were hypothetically willing to see a decline in their own wages in bad economic times as long as everyone else also experiences such a decline, there is no obvious way for a decentralized economy to implement such a plan. Instead, workers confronted with the possibility of a wage cut will worry that other workers will not have such a wage cut, and so a wage cut means being worse off both in absolute terms and relative to others. As a result, workers fight hard against wage cuts.

These theories of why wages tend not to move downward differ in their logic and their implications, and figuring out the strengths and weaknesses of each theory is an ongoing subject of research and controversy among economists. All tend to imply that wages will decline only very slowly, if at all, even when the economy or a business is having tough times. When wages are inflexible and unlikely to fall, then either unemployment, in both the short-run or long-run, can result.

This analysis helps to compensate for the limited instances in which we have observed capitalist economies moving toward a full employment equilibrium on their own. In essence, orthodox economists maintain that full employment is guaranteed by flexible wages; and if full employment doesn’t appear to be happening, it must be because wages are not flexible.

Why Prices Might Be Sticky Downward

Orthodox economists also argue that other prices in the economy are vulnerable to the stickiness problem. While major online retailers and service providers like Amazon and Uber can change their prices instantaneously, this flexibility is not available to the majority of businesses. In most cases, firms do not change their prices every day or even every month. When a firm considers changing prices, it must consider two sets of costs. First, changing prices uses company resources: managers must analyze the competition and market demand and decide the new prices, they must update sales materials, change billing records, and redo product and price labels. Second, frequent price changes may leave customers confused or angry—especially if they discover that a product now costs more than they expected. These costs of changing prices are called menu costs—like the costs of printing a new set of menus with different prices in a restaurant. From this perspective, prices do respond to forces of supply and demand, but from a macroeconomic perspective, the process of changing all prices throughout the economy takes time.

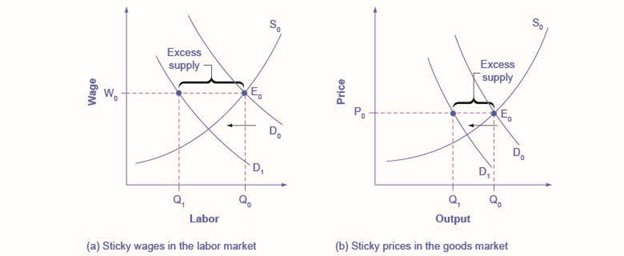

To understand the effect of sticky wages and prices in the economy, consider Figure 1 (a) illustrating the overall labor market, while Figure 1 (b) illustrates a market for a specific good or service. The original equilibrium (E0) in each market occurs at the intersection of the demand curve (D0) and supply curve (S0). When aggregate demand declines, the demand for labor shifts to the left (to D1) in Figure 1 (a) and the demand for goods shifts to the left (to D1) in Figure 1 (b). However, because of sticky wages and prices, the wage remains at its original level (W0) for a period of time and the price remains at its original level (P0).

As a result, a situation of excess supply—where the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded at the existing wage or price—exists in markets for both labor and goods, and Q1 is less than Q0 in both Figure 1 (a) and Figure 1 (b). When many labor markets and many goods markets all across the economy find themselves in this position, the economy is in a recession; that is, firms cannot sell what they wish to produce at the existing market price and do not wish to hire all who are willing to work at the existing market wage. The Clear It Up feature discusses this problem in more detail.

The Great Recession and Slow Wage Adjustments

The recovery after the Great Recession in the United States was slow, with wages stagnant, if not declining. In fact, many low-wage workers at McDonalds, Dominos, and Walmart have threatened to strike for higher wages. Their plight is part of a larger trend in job growth and pay in the post–recession recovery.

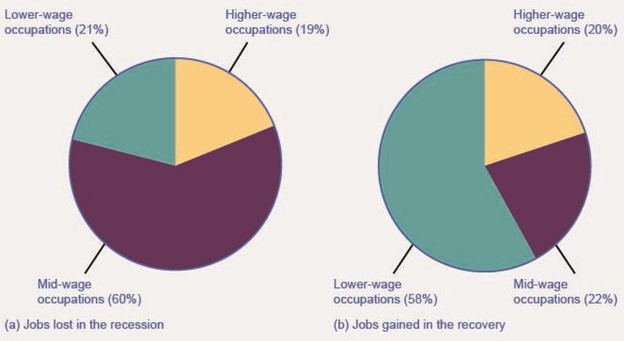

The National Employment Law Project compiled data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and found that, during the Great Recession, 60% of job losses were in medium-wage occupations. Most of them were replaced during the recovery period with lower-wage jobs in the service, retail, and food industries. Figure 2 illustrates this data.

Wages in the service, retail, and food industries are at or near minimum wage and tend to be both downwardly and upwardly “sticky.” Wages are downwardly sticky due to minimum wage laws. They may be upwardly sticky if insufficient competition in low-skilled labor markets enables employers to avoid raising wages that would reduce their profits. At the same time, however, the Consumer Price Index increased 11% between 2007 and 2012, pushing real wages down.

The Synthesis of Keynesian and Neoclassical Models

The neoclassical model, with its emphasis on aggregate supply, focuses on an economy that inherently tends, through well functioning markets, toward the full employment level of production. Because of its emphasis on the tendency toward full employment, the neoclassical view is not especially helpful in explaining why unemployment moves up and down. Nor is the neoclassical model especially helpful when the economy is mired in an especially deep and long-lasting recession, like the 1930s Great Depression.

By merging neoclassical and Keynesian ideas the New-Keynesian model, built on the importance of aggregate demand as a cause of business cycles and complimented by a degree of wage and price rigidity. This framework expands orthodox economics ability to explain changes in cyclical unemployment.

Robert Solow, the1987 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, described the dual approach in this way:

“At short time scales, I think, something sort of ‘Keynesian’ is a good approximation, and surely better than anything straight ‘neoclassical.’ At very long time scales, the interesting questions are best studied in a neoclassical framework, and attention to the Keynesian side of things would be a minor distraction. At the five-to-ten-year time scale, we have to piece things together as best we can, and look for a hybrid model that will do the job.”

Many modern macroeconomists have spent considerable time and energy trying to construct models that blend the most attractive aspects of the Keynesian and neoclassical approaches. It is possible to construct a somewhat complex mathematical model where aggregate demand and sticky wages and prices matter in the short run, but wages, prices, and aggregate supply adjust over the longer run. However, creating an overall model that encompasses both Keynesian and neoclassical models is not easy.

Navigating Uncharted Waters

During the Great Recession, many of the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies that were implemented, designed to boost or support aggregate demand, could be interpreted as New Keynesian. Were these policies effective? Many orthodox economists found that they were, although to varying degrees. Alan Blinder of Princeton University and Mark Zandi for Moody’s Analytics found that, without fiscal policy, GDP decline would have been significantly more than its 3.3% in 2008 followed by its 0.1% decline in 2009. They also estimated that there would have been 8.5 million more job losses had the government not intervened in the market with the TARP to support the financial industry and key automakers General Motors and Chrysler. Federal Reserve Bank economists Carlos Carvalho, Stefano Eusip, and Christian Grisse found in their study, Policy Initiatives in the Global Recession: What Did Forecasters Expect? that once the government implemented policies, forecasters adapted their expectations to these policies. They were more likely to anticipate increases in investment due to lower interest rates brought on by monetary policy and increased economic growth resulting from fiscal policy.

The difficulty with evaluating the effectiveness of the stabilization policies taken by the government in response to the Great Recession is that we will never know what would have happened had the government not implemented those policies. Surely some of the programs were more effective at creating and saving jobs, while other programs were less so. The final conclusion on the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies is still up for debate, and further study will no doubt consider the impact of these policies on the lives of the American people and the rest of the world.

Summary

The New-Keynesian perspective extends the traditional neoclassical orthodox perspective and considers changes to aggregate demand to be the cause of business cycle fluctuations because of wage and price stickiness. New-Keynesians are likely to advocate that policy makers actively attempt to reverse recessionary and inflationary periods because they are not convinced that the self-correcting economy can easily return to full employment.

The neoclassical perspective places more emphasis on aggregate supply. Neoclassical economists believe that long term productivity growth determines the potential GDP level, and that the economy typically will return to full employment after a change in aggregate demand because of wage and price flexibility. Skeptical of the effectiveness and timeliness of New-Keynesian adaptation of the orthodoxy, neoclassical economists are more likely to advocate a hands-off, or fairly limited, role for active stabilization policy.

Lastly, while New-Keynesians would tend to advocate an acceptable tradeoff between inflation and unemployment when counteracting a recession, neoclassical economists argue that no such tradeoff exists. Any short-term gains in lower unemployment will eventually vanish and the result of active policy will only be inflation.

a significant decline in national output

an unwritten agreement in the labor market that the employer will try to keep wages from falling when the economy is weak or the business is having trouble, and the employee will not expect huge salary increases when the economy or the business is strong

the theory that the productivity of workers, either individually or as a group, will increase if the employer pays them more

if employers reduce wages for all workers, the best will leave

those already working for the firm are "insiders" who know the procedures; the other workers are "outsiders" who are recent or prospective hires

costs firms face in changing prices

a situation where wages and prices do not fall in response to a decrease in demand, or do not rise in response to an increase in demand