14.5 – Trends in the Distribution of the Surplus

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the trends in the distribution of income, particularly between workers, managers, and business owners since the 1960s

- Explain various explanations for these trends

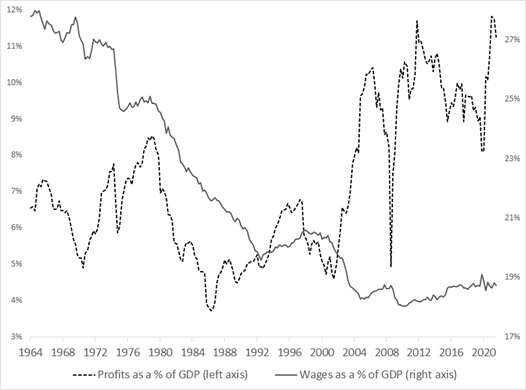

Figure 1, below, indicates how the distribution of the surplus between workers’ wages and businesses’ profits has changed over time in the US. It becomes clear from these numbers that workers have been getting a smaller slice of the pie since the 1970s, while corporations began getting a much larger slice, especially since the 2000s. In this section, we’ll consider some of the history that explains these changes, considering, again, that the distribution of the surplus ultimately reflects a complex array of power struggles.

Note that the data in figure 1 are expressed as a percentage of nominal GDP. This allows us to look at how the share of the surplus (which, in essence, is GDP) has changed over time, abstracting from changes in technology, labor productivity, corporate structure, prices, and the like. Clearly, workers today get a smaller share of that surplus in the form of wages, and corporations get a larger share in the form of profits, than was the case in the mid-20th century. And there are many historical explanations for why this change has occurred; but we’ll focus on three particularly relevant ones.

First, there was the process of deindustrialization: the reduction of heavy industry and manufacturing in a country. In the U.S., this became prominent in the 1980s as manufacturers, especially in Japan and Germany, and later China and elsewhere, began to take the place of previously domestic production. Because these sectors of the U.S. economy had traditionally seen high rates of union membership, the overall result was that workers lost some power in the struggle over the surplus.

Second, as workers lost power, corporate managers gained it. And they did what people tend to do as their power grows: try to get even more power. Management did this, in part, by building empires of non-production workers–growing sales forces, new layer after new layer of supervisory positions, and the like. The resulting bureaucratic bloat, which most people might associate with big government, became the norm for big business as well. And, of course, the salaries of all these additional corporate employees represent their own slice of the pie. This shows up implicitly in figure 1 above in the shrinking of the wages of non-managerial workers.

And third, especially since the 1980s, U.S. corporations have become increasingly concerned with their performance on the stock markets over all other matters. This is reflected in part by the way top managers at these corporations are paid: although we normally think of CEOs, CFOs, and their C-suite colleagues as earning healthy salaries and other benefits like high-grade health insurance, use of a company jet, and an expense account, they’re also paid with the company’s own stock. This practice began in the 1950s but really took off starting–you guessed it–in the 1980s.

Supposedly, paying executives in company stock helps to align their interests with the shareholders–which is true so far as it goes, but doesn’t necessarily mean their interests are aligned with workers, the economy as a whole, or even with building a more competitive company. Instead, this form of management compensation really turns their interests from the production of quality products and the creation of good jobs to the extraction of a greater share of the surplus. This is done in two ways: first, many businesses return a part of their profits in the traditional method of paying its shareholders dividends. Second, an increasingly common practice over the last several decades, many businesses will purchase their own stocks back off the stock exchanges. These share repurchases (or stock buybacks) tend to put upward pressure on the share price, allowing shareholders, including the management of the company itself, to realize capital gains by selling their shares.

In a Harvard Business Review article from 2014, economist William Lazonick notes that the “449 firms in the S&P 500 that were publicly listed from 2003 through 2012…used 54% of their earnings—a total of $2.4 trillion—to buy back their own stock. Dividends absorbed an extra 37% of their earnings. That left little to fund productive capabilities or better incomes for workers.” This shift, Lazonick argues, reflects a change in the business model of large American corporations, from retain-and-reinvest to downsize-and-distribute. That is, prior to the late 1970s-early 1980s, corporations generally used their profits to invest in new enterprises, research and development, and other means of growing and innovating. By the 1980s, however, the increasingly dominant mindset among corporate executives was concerned chiefly with cutting (especially labor) costs to expand profits, and then distributing those profits to themselves and the other shareholders. This new way of doing business focused first and foremost on the extraction of the surplus, not its creation.

And all three of these developments have reinforced each other over the years. For instance, as workers lost the ‘seat at the table’ and the ability to share in the growth of output that unions provided, managers became more concerned with surveilling them to keep output up and labor costs down. This in turn required more layers of management, which meant the executives grew more and more distant from the actual production of the things their companies produced. Greater distance from production then meant managers drew closer and closer to, in essence, Wall Street–that is, the brokers, private equity firms, and so on, who traditionally care more about financial returns than the actual goods and services being created. And this in turn led to profits being diverted from real investment and into financial manipulations.

Now, all of this might simply look like a zero-sum process, where stockholders and corporate executives get a larger slice of the pie as workers get a smaller slice. And, depending on your perspective, that might even be a justified change. But in fact these historical patterns over the last 40 or 50 years appear to have kept the pie itself from growing as fast as it otherwise could as real investments as well as labor productivity have slowed in recent decades.

References

Lazonick, William. 2014. “Profits without Prosperity.” Harvard Business Review. Available at https://hbr.org/2014/09/profits-without-prosperity.

YouTube video summarizing Lazonick’s article for course shells: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sxn2Ru5MmJw

Glossary

- share repurchases (stock buybacks)

- when publicly traded corporations purchase their own stock back off the stock exchanges

the reduction of heavy industry and manufacturing in a country

a direct payment from a firm to its shareholders

when publicly traded corporations purchase their own stock back off the stock exchanges