35.2 – Human needs, Satisfiers, and Democratic Decision-Making

Learning Objectives

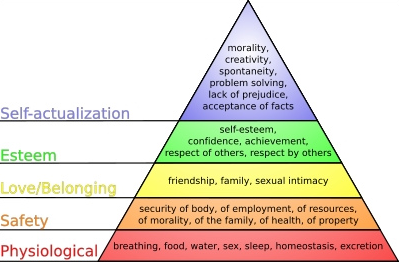

- Identify the five levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

- Explain the relationship between human needs and their satisfaction through a social provisioning process

- Discuss the concept of consumption as a democratic decision-making process

We can now see that the project of sustainable social provisioning centers on the notion of empirical human needs. Economists[9] alongside social and behavioral scientists have distinguished different human needs.

Human Needs Distinction

One of the most widely known is Abraham Maslow’s distinction of human needs:

Maslow’s distinction of needs is consistent with Aristotle’s insight that human needs are few and finite, rather than unlimited and non-satiable. It also echoes the ancient wisdom that “man does not live by bread alone”, highlighting the importance of social and spiritual needs. Importantly, the distinction does not mean that the more spiritual need for self-actualization is a luxury that can be postponed until the other basic needs are satisfied. The converse holds true, namely, the more immaterial needs provide meaning and measure for the pursuit of material needs. Immaterial social-psychological and spiritual needs do not require market exchange or the consumption of material resources. Instead, they require “free time spent in an intelligent manner”.[1] For instance, economic conduct such as the conspicuous consumption of fashionable sneakers is an expression of the social-psychological need for self-esteem derived from the increased status acquired by such purchases. While shoes satisfy the need for walking safely and rapidly without incurring injuries, self-esteem and the corresponding happiness can also be obtained in more healthy and sustainable ways that do not involve material consumption. Indeed, the net result of the human economy is defined as a spiritual magnitude or psychic flux associated with enjoyment of life.[2] Whilst the meaning of this spiritual flux is interpreted differently by different philosophies it seems safe to say that it can serve to ameliorate, cultivate, and dignify material existence.

This implies that the hierarchy of needs is not set in stone as needs are interwoven with a tendency to become unbalanced or to be left unsatisfied unless carefully and constantly calibrated and provisioned for. As an example, the need for self-esteem can override even physiological needs when advertisement, peer pressure or social media addiction cause mental, physical illness, and unsustainable levels of waste from throw-away consumerism. Another example is the effect of either deprivation or a too-exclusive focus on physiological and safety needs, which can either prevent or lack in self-actualization. On the other hand, an exclusive focus on self-actualization may not secure the satisfaction of physiological needs. Returning to the example from above, it is possible to satisfy the need for safe walking by purchasing an inconspicuous and relatively inexpensive pair of shoes while fulfilling the need for self-esteem through self-actualization as in achieving mastery of a certain know-how or body of knowledge. In conclusion, human needs are not perfectly substitutable, but more akin to complements that need to be satisfied in a balanced, healthy, and sustainable manner to obtain the desired result of human prosperity.

Alternatives to Consumerism – Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic

This way of thinking about the good life is also at stake in recent discussions following the experience of Covid-19 lockdowns, which have provided a glimpse of a less work-intensive, less consumeristic, and less wasteful society with a cleaner environment:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/08/pandemic-covid-19-work-society

Human need satisfiers

More recently economist Max Neef has distinguished the modes of being, having, doing, and interacting as satisfiers for various human needs. Neef’s matrix can be adjusted slightly to reflect better Maslow’s above distinctions of human needs.

| Human Needs | Being | Having | Doing | Interacting |

| Self-actualization/

Self-esteem (Leisure, Creation, Identity, Freedom) |

Sense of belonging, self-esteem, imagination, curiosity, tranquility, spontaneity, autonomy, openness | Games, parties, peace of mind, abilities, skills, language, norms, meaning, equal rights | Day-dream, remember, fun, relax, get to know oneself, grow, commit oneself, dissent, develop awareness | Landscape, intimate spaces, spaces for solitude, spaces for expression, workshops, spaces of belonging |

| Love/Esteem: (Affection/ Participation/ Understanding) | Respect, humor, generosity, sensuality, criticality, intuition, curiosity, receptiveness, dedication | Friendship, family, relationship with nature, literature, teachers, policies, responsibilities, duties, work | Share, take care, make love, express emotions, analyze, study, meditate, cooperate, dissent | Privacy, intimate spaces, schools, families, communities, associations, parties, neighborhoods |

| Safety (Protection) | Care, adaptability, autonomy | Social security, health systems, work | Cooperate, plan, take care, help | Social environment, dwelling |

| Physiological (Subsistence) | Physical and mental health | Food, shelter, work | Feed, clothe, rest, work | Living environment, social setting |

| Adjusted from Max Neef in Daly/Farley, Ecological Economics – Principles and Applications (2nd edition) 2010, Island Press. | ||||

This matrix highlights the non-market character not only of the human needs themselves but also of the process of satisfying most human needs in what is essentially a social provisioning process of satisfiers. Looking, for example, at the “interacting” column we can see that the provision of quality public spaces accessible to everyone is essential, such as natural beauty spots, recreational facilities, and environmental amenities, such as forests, lakes, parks, and thriving healthy neighborhoods. There are costs attached to the social provision of these spaces as satisfiers, which need to be carefully assessed in a deliberation process that ensures air, water and soil pollution of these spaces are not above safe levels indicated by the World Health Organization. This satisfies the human need for safety through drawing up good plans (“doing”), adopting a caring attitude (“being”), and tools or assets (“having”). As is apparent, such a process of determining and relating means and ends can easily result in goal conflicts, which have to be resolved in a careful deliberation process involving qualitative and quantitative judgment.

Social Needs and Democratic Consumption Decisions

For example, which human need and which satisfiers are being prioritized given limited resources and social opportunity costs in the sense of forgone alternatives for present and future generations? This question points towards the section below on evaluating the social cost of social provisioning. This process resembles a democratic decision-making process of consumption, according to which the community decides which satisfiers it prioritizes, or to which degree it provides each satisfier. There may be communities that prioritize safety over self-actualization, or the other way around. This would result in a different set of priorities for social provisioning. Human needs and human rights are thus translated into social needs and social rights as individuals in society recognize the responsibilities for the whole of society and humanity.

Communities may make distinctions of who will be prioritized in being provisioned with satisfiers because they deserve special protections, such as for example the elderly or sick during pandemics or war. This may also apply to distinguishing between different sectors, industries, and segments of workers, who are more relevant than others for safety and protection needs within the social provisioning process. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic the government deemed the commercial airline industry, tourist industry, hospitality sector, and barbers less important than hospitals, dentists, universities, and food shops. The former sectors were shut down or limited in their operations during lock-down, while the latter remained open under certain conditions. The same was true for defining a list of professions that were labeled “key workers”, such as nurses and educators for the maintenance of the social provisioning process.

Unfortunately, the social provisioning of even these most basic satisfiers is far from guaranteed, remaining an ongoing challenge even, or perhaps especially, in the so-called “advanced” countries of the world that are considered “wealthy” in terms of the magnitude of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). There are plenty of examples of these unpaid social costs or social cost deficits, which can be found in the environment section of quality broadsheet newspapers every day. For example:

“Virtually every home in the UK is subjected to air pollution above World Health Organization guidelines, according to the most detailed map of dirty air to date. More than 97% of addresses exceed WHO limits for at least one of three key pollutants, while 70% of addresses breach WHO limits for all three. […] The WHO says air pollution is the biggest environmental threat to human health and is a public health emergency.”[3]

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1979) “Minimal Bioeconomic Program” in Energy and Economic Myths, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ↵

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1979) “Minimal Bioeconomic Program” in Energy and Economic Myths, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ↵

- The entire article on this research can be found here: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/apr/28/dirty-air-affects-97-of-uk-homes-data-shows. Have a look at other relevant reporting: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/environment https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/apr/12/i-have-swum-through-sewage-far-too-often-why-cant-we-take-better-care-of-our-rivers https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/may/03/why-are-american-national-parks-filled-with-plastic ↵