35.4 – Cost Shifting in Capitalism

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss various forms of cost shifting and how they create social cost deficits

- Explain the legal and illegal foundations of cost shifting

Market exchange as a mode of allocation does not provision for the needs of those without purchasing power (the poor) and they do not reflect the needs of future generations. In this sense they are incomplete. In other words, markets may be formally rational while not being substantively rational as they do not guarantee that all human needs are met through the social provisioning process.

But there is another way in which markets are incomplete: market prices do not reflect the full cost of production. This is because the capitalist cost accounting of firms does not reflect all the costs necessary to secure sustainable social provisioning. In other words, businesses socialize parts of the total costs of production in their quest for profits. In this light, privatized profits may be viewed as the flip side of socialized costs.

Private Costs + Social Costs = Total Costs

Private Costs – Total Costs = Socialized or Shifted Costs

Shifting more costs >> higher private profits

Cost Shifting: Social Cost Deficits

Firms shift costs to society, future generations, or third parties (consumers, workers, neighbors etc.) and leave them unaccounted and uncompensated for. This implies that the private sector runs a social cost deficit, which turns into a social cost debt over time.

Socialized or Shifted Costs = Social Cost Deficit

Social Cost Deficit: Unpaid gap between actual and minimal levels of human need satisfaction

When firms avoid responsibility for social costs by not accounting for them and leaving them unpaid, they essentially shift them to society at large, third parties and future generations. This leaves behind a gap between the actual and necessary basic level of human need satisfaction. This implies unmet human needs and forgoing the full flowering of humanity, which is a social opportunity cost of not paying social costs of social provisioning. Because this is costly to the whole of humanity and society not to pay social costs it can be described as socially wasteful in the sense of socially inefficient.[1] Because costs are typically shifted towards the weak and vulnerable, society at large or future generations they also constitute a social injustice. It is thus possible to say that the critique of cost shifting and concern for social costing of social provisioning is not just about sustainability, but also social justice and efficiency. Again, the goal is to prevent and reduce social deficits before they occur, not just compensate for them after they occur. As with harms to human health prevention of damages and losses is cheaper than fixing or repairing them. And, given that certain harms, damages or losses are irreversible prevention and precaution are key and consistent with the Kantian ethic concerning human dignity.

Whether or not societies acknowledge and take responsibility for social costs can have a significant impact on the levels of happiness and human development as measured by the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Program or the World Happiness Report published by the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network. For example, it is cheaper and more conducive to happiness to prevent illness than it is to deal with disease through markets or compensation. Countries such as Switzerland (2), Finland (11) and New Zealand (14) rank higher in human development than the United States of America (17) as well as in terms of happiness (3, 1, 8, 18 respectively)[2] expressed not least in their higher life expectancies, and lower infant mortality.

Cost Shifting: Profits from Public Subsidy

Present profits are derived from cost shifting, which implies social cost deficits. In some cases, social cost deficits get picked up by the governmental sector who pays for social costs out of tax revenues or by running government deficits. Today’s ballooning government debts around the world are to some extent the result of paying for parts of the social cost deficits created by the private sector. This is essentially a public subsidy for capitalist firms and their owners who can reap higher profits while not paying their bill, and instead sticking it to society. Conversely, the working classes are unable to engage in similar cost shifting and do not receive equivalent subsidies. Instead, they are thrown to the uncertainties of labor and consumer markets. The phrase appropriately coined for this mechanism is: socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.

Profits = Social Cost Deficits

Social Cost Deficits = Public Subsidies

Public subsidies = Government Debt

For example, fossil fuel companies shift costs of pollution related damages worth 5.9 trillion USD in 2020 alone, according to estimates of the International Monetary Fund. As most of these damages are not compensated for by governments they become a social cost debt heaped upon the future. Social cost deficits resulting from cost shifting are a kind of public or social subsidy for the private sector who can dump, damage and destroy free of charge, while reaping enormous profits. The oil and gas sector has gained on average 1 trillion USD of annual profits for the past 50 years. However, this is not all. The fossil fuel industries also receive subsidies worth 700bn USD in 2021 as governments keep energy costs artificially low, thereby controlling prices and keeping demand artificially high for harmful fossil fuels. For example, highly energy intensive industries in Germany benefit from tax regulations that permit writing off costs for energy above a certain threshold. Another example is the budget airlines in Europe that are exempt or benefit from reductions in fuel taxes.

Another example, firms employ workers who arrive equipped with education, the social as well as the necessary technical skills, which were obtained in a long process of learning and socialization. Shouldered by society in the form of schooling, technical education, unpaid household labor, and child-care work, this process takes around 20 years in today’s technically advanced societies. The community’s joint stock of technical as well as cultural knowledge[3] embodied by workers is utilized by companies at a fraction of the costs. This is so because wages and taxes paid by companies are insufficient to pay for the full costs of social reproduction of this process, which reflects the social costs of human needs of education, care, nutrition, housing, etc. Firms also take for granted that they can let go of workers when they are no longer needed without having to worry about their maintenance–that is, their social costs. Because unions have been weakened by a series of governmental policies and legal reforms this kind of cost shifting often goes unchallenged.

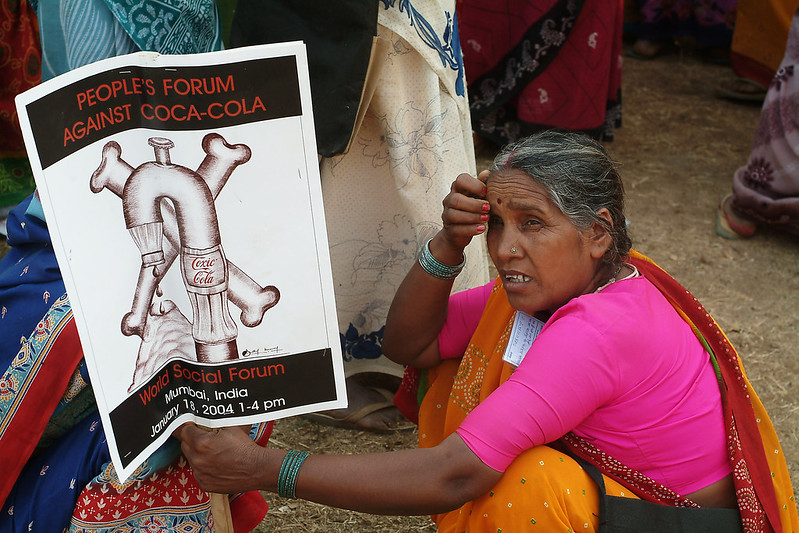

The same is true for non-renewable natural resources, such as stocks of underground water and fossil fuels (coal, gas, oil), which are absolutely finite or scarce. Nevertheless, firms can transform these resources irrevocably into waste without consulting future generations, and without having to pay the full replacement, depreciation or user costs. For instance, to produce soft drinks the Coca-Cola corporation extracts underground water from locations that are experiencing water shortages or rapidly declining water tables. They are given permission by local authorities to do this at a price that is a small fraction of what households have to pay for the same water. This kind of cost shifting raises resistance from local citizens and environmental groups.

Similar issues emerge surrounding livestock industries that do not have to pay for the groundwater pollution from meat production, passing costs on to households who now pay for more expensive water filtration by local water companies. This cost avoidance through cost shifting is basically a legalized practice of depleting precious non-renewable resources and filling the ecosystems with their waste products, which results in social cost deficits. The social opportunity costs of this resource depletion as well as pollution of sinks are thus mostly shifted towards future generations and society.

Cost Shifting: Legalized Social Fraud

Social cost deficits indicate a kind of accounting fraud as capitalists only record those costs that are contractually or legally mandated and technically necessary. From a societal perspective this intentionally incomplete cost accounting is not rational. The firms’ monetary accounting and the national income accounts built thereon are incomplete, hiding social cost deficits to a large extent. These artificially low cost-accounts and artificially high profit accounts give the impression that the system is growing. This is then often erroneously associated with progress or even development, while in reality it is leaving behind social cost deficits that undermine sustainable social provisioning.

Even worse is the fact that some preventable social costs are mis-accounted for as profits, income or growth, when they are remedied in a market transaction, such as a firm’ repair job, or government programs to clean the environment after an oil spill. In other words, the accounting is flawed in two ways, first by not accounting properly for social costs, such as environmental pollution, and then counting the fixing of the damage as a gain to the system when it is clearly not a gain. Increasing government deficits and debt due to rising costs of environmental, health and social payments indicate that cost shifting is increasing cumulatively and exponentially. And the owners of government debt can even profit from these assets, meaning that the public sector is subjugated to the profit logic of the private sector. Social cost deficits also appear directly in a variety of indicators measuring pollution levels, species extinction, global warming, resource depletion, poverty, declining life expectancy, health care crises, financial instability etc. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 was a case in point as the privatization of financial sector profits was accompanied by the socialization of costs from toxic assets that were shifted to the public balance sheet as government deficits in exchange for fresh cash. From these considerations appears the specter that profit levels of businesses or industries are reflective of their respective ability or power position to socialize the costs of production. This broadly confirms Veblen’s theory of the predatory nature of business enterprise whose “strong arm”[4] overpowers the “invisible hand.”

Cost Shifting: The Legal Foundations of Private Property and Capitalist Accounting Laws

The ability of capitalists to avoid responsibility for the costs of reproducing society through cost shifting is based on the principle of investment for profit which is globally enforced by capitalist accounting laws. These laws mandate businesses to conserve financial capital only, treating all other production factors, such as labor and natural resources, as mere assets. These capitalist accounting rules were invented in 14th century Northern Italy and became enforced globally over time, instituting the definition of capital as money sums for purposes of double entry bookkeeping. Arguably, capitalist accounting is the beginning and core institution of capitalism. However, a firm’s capital is recorded as a liability on the right-hand side of the balance sheet, implying a debt to the firm’s owners. The latter hold property titles to this capital. In other words, property, which enables legal and tradable titles to debt contracts, is a necessary legal precondition for capitalism. Nevertheless, cost shifting also occurs in nominally socialist and communist countries who have adopted globally enforced capitalist accounting rules. This implies that cost shifting occurs regardless of who owns property, whether the government or capitalists. Socializing property is thus insufficient to eliminate cost shifting. Rather, reforms of accounting standards in conjunction with changes to property rights are required.

Arguably, the combination of the institutions of private property and capitalist accounting rules are the legal foundations of capitalism and cost shifting. Assets, such as workers and natural resources, can be economized upon without paying full costs of reproduction. There is no obligation to conserve assets and they may be prematurely exhausted through overuse for short-term profits. Typically, capitalist firms only account for those monetary costs that they must pay due to minimal technical requirements of production and institutional requirements, such as legal standards, laws, and contractual agreements. In other words, the factors of production – labor and natural resources – become sources of profit to business as it can shift parts of the costs of reproduction.

Social costs are neither accidental nor unpreventable occurrences like, for example, the natural disaster of a volcano eruption. They are systemic, predictable, and preventable economic phenomena and problems, rooted in private property and capitalist accounting laws that determine the calculation rules for profits and legalize cost shifting. This could be changed however, and institutional reforms could make cost shifting illegal and unprofitable. The full costs of production would thus be borne by private producers rather than society and future generations.

Preventing social costs at the source would necessitate a change of global accounting standards for capital, such that financial capital can no longer be conserved by running social cost deficits. One such proposal for accounting reform is to protect human and natural capital under the same conservation rules as financial capital. This would make social cost deficits impossible that arise from firms’ non-full cost accounting.[5]

Cost Shifting: The Illegal Dimension

Lawful cost shifting is not the only source of profit or cause of social-ecological damages. Indeed, it seems that business has run out of legal ways of maintaining desired profit rates through cost shifting. As a result, capitalism as a system of socializing costs goes increasingly rogue, shifting costs beyond the frontier of the law. This is so because the past twenty years have seen an explosion of unlawful cost shifting practices of corporations. Whereas the highest corporate fine in the year 2000 was 900 million USD[47] for the pharmaceutical corporation Roche, more recent fines and compensation payments for breaches of law or compensation have reached astronomical levels of 25 billion for VW diesel emissions scandal, 15 billion for the BP Deepwater horizon oil spill disaster. The 5 billion USD fines for financial fraud committed by Allianz Insurance corporation are considered such “peanuts” today that they don’t make for good headline news and the public barely take notice anymore. This indicates that corporations increasingly treat the law as a cost of doing business in the sense that the costs of breaking the law are lower than the profits from it. In many cases the fines and compensations actually paid out are a fraction of the profits made from unlawful actions.[6] For instance, VW had the most profitable year in its history the year after the diesel scandal broke.

Cost Shifting from Financialization

The global enforcement of accounting standards for financial capital not only enshrines the principle of investment for profits, the conservation of financial capital, and the social cost deficits arising from cost shifting; they are also rooted in the institution of private ownership, which propels the expansion of the capitalization process through increasing financial debts. This is made possible thanks to ownership titles serving as collateral in property-based economies. The debt expansion process occurs today under the command of corporate finance in a fractional reserve banking system. This system results in the inflation of all monetary values, which further sustain an expansion of debt. The latter becomes a tradable asset in an overall financialization of the capitalization process. This means that managerial decisions are increasingly controlled by financial sector interests.

For example, in the pursuit of profits banks extend credit to fund investments in fossil fuel exploration and production, which will push global warming beyond the tipping point of 1.5-degree warming. At the same time, investment funds hold assets of fossil fuel companies due to their high profit rates from cost shifting. In other words, cost shifting is one of the main sources of financial sector profitability. There is thus a trade-off between the short-termism driving the expansion of the financial sector and the long-term interest in sustainable social provisioning. This has been labeled the “disconnect between Wall Street and Main Street”. What this means is that stock market performance of the financial sector has disconnected itself from the real sector economy in the sense that it thrives not only when the real sector declines but because the real sector declines. Again, the profits of financial firms reflect increasing social cost deficits and a socio-ecological vicious cycle.

Financialization is today a major driver of cost shifting and social cost deficits. Financialization means that short-term shareholder value maximization is increasingly pursued not through real sector sustainable investments but through mergers and acquisitions, stock-buybacks, and increasing debt-leverage. This has major social opportunity costs. Increasing debt-income ratios lead to financial instability, become unsustainable, and ultimately require government or public money bailouts. Mergers and acquisitions typically mean reductions in employment. Payments of dividends to shareholders imply foregone investments, employment, and output in the real sector. Payment of bonuses to money managers are costs of doing business that have to be recuperated elsewhere through cost shifting.

The income of the financial sector is rent taken from real disposable income from the producing sectors. All rent is non-productive as it does not create social use value. It is essentially a kind of tax exerted by the financial sector on the rest of the economy. This rent mostly goes to conspicuous consumption as a way of wasting society’s surplus. One notable example is the 2021 news that champagne sold out in the banking district of London as investment bankers celebrated their most profitable year in history and the unprecedented levels of bonuses they received when the economy experienced the sharpest decline in its history. This implies high social costs as foregone opportunities of using such funds for human need satisfaction and social provisioning. Notoriously underfunded and underperforming public infrastructure, public transport, public schools, and health services are the most glaring examples. The waiting lists of the National Health Service in the UK show several million people waiting for months if not years for essential treatments, such as cancer surgery.

Cost Shifting in the Neoliberal Predator State

Today mixed economies organize social provisioning predominantly through two dominant and interlinked sectors, consisting of large multinational corporations and the government. The expenditure of the latter accounted for approximately 47% of GDP in the USA in 2020. Due to neoliberal reforms since the 1980s many governments have privatized and deregulated many assets and functions. This means that corporations have taken control of the profitable segments of government assets and contracts, while leaving the unprofitable segments to be funded by the taxpayers. As a result, they are no longer subjected to effective public scrutiny over their compliance with health and safety regulations. In essence this is a predatory process as it leads to more cost shifting, which is a redistribution of income and access to key public goods from the poor to the rich. This process has been supported by a political movement called neoliberalism, which believes in imposing markets and privatization for every aspect of society. It works through the “revolving door” mechanism, in which executives of corporations become chairs of government agencies and ministries, and even heads of government. In these positions they often further the interests of their former employers to whom they often return after their stint in government expires. Democratic governments today often justify this take-over by private interests as mere “information sharing”, but in reality, it is a way for capitalist corporations to do more cost shifting.

For example, the privatization of water companies in the UK has resulted in 95% of rivers being polluted and toxic . There is nearly no governmental oversight, no enforcement of regulations, and fines pale in comparison with profits from illegal dumping of sludge. The absentee owners reap billions of profits, while avoiding costs not only for proper waste disposal but also the costs for expensive infrastructure investments. This means that every day millions of gallons of water are lost from leaking pipes while many parts of the country are experiencing drought and water shortages. The public has no right to know who polluted the rivers, when and where, and to what extent even in the few cases where the government holds records on this information. This system of cost shifting is possible due to the excellent relations of the rich private owners and managers of water companies with the elites and parties running government.

The concept of the neoliberal predator State is not entirely new. Indeed, the problem of the soft State and ineffective administration that is corrupted by special interests, such as capitalist business interests, was described in the context of development economics. What is new, however, is that the neoliberal predator State has become a system of cost shifting through the marketization of State functions essential to social provisioning. This is more specific than the vague acknowledgment of corruption. The neoliberal predator State is thus characterized by less democratic control of capitalist firms and diminished social provisioning. It also comes with a loss of expertise such that government is often unable to govern without private expertise and information sharing. In this system it is no longer possible to distinguish democratic government from commercial interests.

Cost Shifting vs. Externalities

Social costs reflect real losses, damages, and harms that are often irreversible, remain uncompensated, hidden, and unaccounted for over considerable timespans. They arise from profit driven investments and feed through the chain of production and allocation decisions, choice of technologies, consumption, distribution of incomes, and even exchanges under asymmetric information. They are borne by the socio-ecological system where they can trigger tipping points and increase exponentially due to self-reinforcing mechanisms.

This is particularly treacherous when recognizing this as a cost burden shifted towards future generations. Some have called this a kind of taxation without representation. Others view this as mortgaging the future by leaving the future to pay our costs. Sustainability can thus not be achieved in a cost shifting system as this constrains and diminishes the potential for satisfying the needs of future generations. Also, the future is thereby already burdened and constrained, reducing freedom for future generations. In a sense, capitalists have found a way to reap profits from enslaving the future by shifting present costs towards it.

This demonstrates that social costs cannot be adequately captured as a linear, reversible exchange process between present individuals with perfect knowledge, as in the theory of “negative externalities”. Not only are future generations and the actual mechanisms of socio-ecological systems ignored in this orthodox economic theory, the theory also mischaracterizes the socio-ecological nature of social costs. The suggestion that these phenomena are “external” adopts the bias of a closed economic system whose internals have no relations and do not depend on socio-ecological systems. Nothing could be further from the truth as they are 100% internal. The substantive understanding of economy shows that the economy is an open system that is embedded in open ecological and social systems, which provide the natural and cultural resources for its survival.

Moreover, the orthodox theory is not a preventative and precautionary approach, as negative externalities are portrayed as given or accidental, and fixable through taxation or bargaining between individuals. There is no analysis of the institutional and systemic causes, and thus no attempt to fix capitalist accounting rules and institute a social costing procedure for the social provisioning for human needs more generally.

- The notion of social waste in the sense of social inefficiency or social opportunity cost was developed in great detail by Thorstein Veblen as a critique of the system of business enterprise. This book can be read for free at https://www.geocities.ws/veblenite/txt/tbe.txt ↵

- Ranking data taken from 2020 table: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Happiness_Report#2022_report ↵

- For this aspect see Veblen’s theory of capital and ownership in The Foundations of Institutional Economics, Routledge. ↵

- See Veblen’s theory of capital in Kapp, K. William (2011) The Foundations of Institutional Economics, Routledge. ↵

- For this proposal see Berger, S./ Richard J. (2021) Alternative national accounting: From monetary to social cost accounting. [Online] at: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/7338217 ↵

- “The Corporation” 1st edition (2003) Documentary Film available at https://www.thecorporation.com/ ↵