4.2 – An Introduction to Ontology

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define and describe three ontological relationships between structures and agents

- Develop examples of subjects that are best understood using each of the three ontological commitments described

- Utilize the following terms: reductionism, duality, aggregation, reflexivity, and embedded, to differentiate orthodox from heterodox economics

So let’s start from the beginning by asking what is real or what is your theory of reality. This is what ontology helps us to sort out. Your ontological grounding is your foundation or the roots of any scientific inquiry. This should make logical sense, because, while fantasy can be useful for sparking ideas, cultivating imagination, and creating a vision, one wants to use science to describe and study reality. Ask yourself what is real and how you know it is in fact real. These are questions that humans have wrestled with for centuries. This is the foundational coding for science. Ontology provides the first commands that guide the procedures of our scientific process.

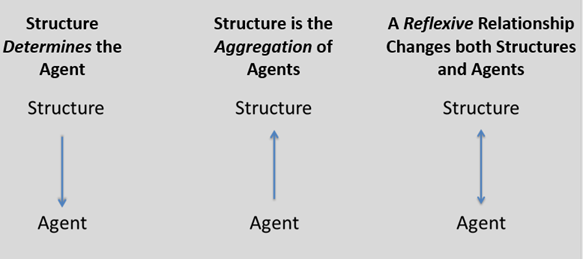

Economics is classified as a social science. Therefore, when we talk about the ontological foundations for economics, we find we are talking about what is called social ontology, or the ontology of society. How can we describe social reality? In this text, we break down social ontology into three different relationships between what we will call structures and agents. One way to begin thinking about these relationships is with a metaphor. Imagine agents as pieces of a puzzle that come together to form something new or a structure. Agents help make up or characterize the structure. An ontological foundation describes the relationship between structures and agents. In Figure 1, we see arrows that distinguish three possible relationships between structures and agents.

In the first relation, we see the arrow pointing down from the structure to the agents. In this top-down form or relation, we say that the structure defines or determines the agents. One social structure that exemplifies this form of ontology is the feudal order. Under feudalism, one was assigned a role in society at birth. If you were born a lord, good for you. If you were born a serf or a slave, then this is your place in society and you must accept this position by living out your life as a dutiful serf or slave. The payoff for behaving and accepting your role as a serf is passage to the Kingdom of Heaven after you pass. One could say, ‘in the long run,’ your sacrifice is rewarded. While this might sound absurd, we will notice similar promises of future rewards are prevalent in the modern rhetoric of orthodox economics.

Rhetoric in Economics

Rhetoric is the use of words to enhance an argument. Rhetoric in economics will be examined throughout this text. Words like rational, efficient, and equilibrium permeate orthodox writings. These worlds often reference specific mathematical assumptions; however, they also possess standard popular meanings. An efficient firm, for example, is a firm that makes allocative decisions among labor and capital that fit the assumptions of the cost-minimizing mathematical model. Unfortunately, the word efficient does not make you think of math, but all the linguistic and cultural ways we think of items as being efficient. This enhances the orthodox argument. Moreover, the language used by orthodox economists, by drawing from the natural sciences, gives many of their arguments a sense of inevitability or of being part of larger natural processes. One of the most egregious examples of this use of language is Milton Friedman’s coinage of the term “the natural rate of unemployment.” If you have ever been unemployed, you probably did not find any aspect of that struggle to feel “natural”. So be aware of words, and how those words are capable of carrying a great deal of meaning beyond the immediate context.

On the flip side, you will notice that the heterodox language is also different. Because heterodox economics is working on building from a different paradigmatic grounding, its descriptions of economic activities are quite different. Examples include describing firms as going concerns or economic activity as the social provisioning process. These words or the rhetoric of heterodox economics is intended to emphasize the evolutionary and ever-changing dynamics that human social systems display.

This determinate relationship produces a very rigid social structure. In fact, part of why humans began to reject the feudal order was a growing understanding and curiosity about free will. But before we move on from the deterministic structure of feudal society, let us take a moment to consider how widespread acceptance of this theory of reality influenced human life. The religiously organized feudal order dominated just about every dimension of life, from work to culture and family life. The separation of various social classes alone prevented the interaction of ideas and closed off possibilities for people to imagine something different. With God and the church, the determining structure of society there is very little room for individual initiative or social change. Further, the assumption that people are born into a particular social status imparts a paternalistic relation that is naturalized and thus unquestioned. Unfortunately, while we have moved beyond the feudal order and embraced free will, elements of feudalism’s repressive assumptions persist and have contributed to many of humanity’s darkest hours: the transatlantic slave trade, Nazi Germany, and fascism more broadly, and most recently, the rise of white supremacy across the Western world are harsh reminders that philosophy matters.

So while we will not spend much more time investigating this deterministic ontological structure, we will refer to its cultural and social influences throughout the text. This serves as an important reminder that ideas and culture constantly evolve, but can also be quite stubborn in their ability to survive no matter how destructive. To this end, a central concept to flag for you as a new social scientist is the individual. Conceptions of individualism, competition, and scarcity, you will see, are in constant tension with dependence, cooperation, and abundance, and represent core differences between the ideas and knowledge these paradigms generate.

The Enlightenment brings many of these tensions into view. The Enlightenment is an intellectual and cultural movement that challenged determinism and worked to set the individual free from the rigid confines of the feudal order. We see this challenge in its most basic form in our second structure/agent relation. The upward arrow indicates free will for the individual by making the structure the summation or aggregation of agent choices. Agents are the smallest component parts of the structure. This ontological foundation is often described as reductionism. We can reduce all structures into individual parts and from the smallest of these parts we can understand the whole. One simple way of describing this ontology is that the whole is equal to the sum of its parts.

A second important characteristic of this ontological foundation is the concept of duality. Duality, in this context, is rooted in Descartes’s cogito ergo sum (I think therefore I am) hypothesis. Descartes argued that because humans think and have consciousness they are capable of observing and understanding the world from an “outside” perspective. This conception of the inside/outside or object/observer attribute of the reductionist ontology is fundamental to much of what we now consider the scientific method. This ontology, for instance, allows scientists to claim to be discovering science, rather than being active participants in its evolution. As we will see in the coming two sections on epistemology and axiology, these claims are contested and significant work remains in this area.

In this text, we refer to this reality or ontology as one of aggregation. Aggregation is a fancy word used to say, we add things up — the whole is equal to the sum of its parts. For instance, the student population is the aggregation of students attending this school. On a deeper level, this ontological foundation grounds consequential knowledge creation about the basic building blocks of life. A prime example is an atom. When we discover and understand atoms, we unlock many of the mysteries of the universe! As such, this ontology is extremely powerful and is the foundation for some of the most powerful epistemologies humans have come to employ in science. One such area of inquiry is orthodox economics. In this case, the agent or smallest unit is modeled by individual choice, both for consumers and for the individual producing unit, the firm. These units are defined by their ‘rational’ and ‘efficient’ choices (see breakout box on Rhetoric). These choices aggregate to form the structure orthodox economists call the perfectly competitive market. In the epistemology section below, the tremendous scientific success grounded by this ontology is described and contrasted with our third ontological foundation, reflexivity.

You might have guessed by now that with one arrow pointing down and the other pointing up that our third ontological foundation is one in which these relationships are viewed as non-exclusive. It is important to understand the relationship between agents and structures as bi-directional. It is not enough to view reality from the ground up or the top-down, because structures influence agents or change them, and on the other side of the coin, agents are capable of changing those structures, especially when it comes to humans and their ability to reason and make decisions. The reflexive relationship between structures and agents changes the simplicity of ‘the whole is equal to the sum of its parts’ to one where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The “greater than” residual introduces significant complications and opportunities for understanding social structures and how human beings come together in groups or what we call institutions.

We define institutions as “collectively shared habits of thought–of knowing, doing, and valuing–that control, expand, and liberate individual action” (See Chapter “An Institutional Analysis of Modern Consumption” for more on this definition). Such institutions or shared habits of thought can be formal and informal. Informal institutions might include taboos, customs, and traditions. While formal institutions are exemplified by constitutions, rules of a game, and property rights. The university or college you are attending is an institution. For a moment think about all the different types of institutions that come together in your schooling. Your school enforces the Student Code of Conduct (formal) while also perpetuating (informal) traditions and norms such as raising your hand in class or keeping your voice down in the library.

Returning to our earlier team chemistry example, the whole or the team is greater than the sum of its parts, it is the team’s chemistry that is the “greater than”. While this chemistry cannot be directly observed by our sensory experience or measured in a specific quantity, it remains the quest of coaches and players to understand how good chemistry is created. This is illustrated by the countless TV analysts who have opined that if only they could capture it in a bottle they would still be coaching. Developing systematic techniques for understanding how or why some systems, institutions, or teams are greater than the sum of their parts requires a fundamentally different set of tools or methodologies than what is available under the ontology of reductionism and aggregation.

Reflexivity, we will see, also calls into question the concept of duality. Is it ever possible to remove the scientist from the social and cultural world they seek to understand, and is such removal even desirable? Sticking with our team analysis, do we understand team chemistry better from an outside observer position, or would we stand to benefit from the players’ perspectives and their descriptions of team chemistry? Additionally, one might inquire as to why our scientist is interested in team chemistry to begin with. Could it be that they themselves experience such a feeling or are they connected to this group due to some other social or cultural experience? In other words, why do we choose to study team chemistry, social inequality, biomechanics, or criminal justice as scientists or economists? Further, why does one study physics or ballet? Put another way, is it ever possible for the study of the economy, or any other subject for that matter to be done from the “outside”?

As you might have discerned from the different definitions of economics, this is a key question. Orthodox economics proceeds, from its aggregation ontology, by seeking understanding or knowledge about the economy as separate and removable from social, cultural, political, and environmental contexts. This is similar to conducting science in a laboratory. We want to control for as many variables as possible and study the phenomena specific to the economy in isolation. In contrast, heterodox economists proceed by studying the economy as embedded in social, cultural, political, and environmental contexts. There is no laboratory for economics. The study of the social provisioning process requires the analysis of the interacting systems.

Let us take a moment to summarize. We have outlined three distinct reality structures. Our first is deterministic and while remnants of the Feudal order remain in today’s society, few adhere to a vision of reality that does not include free will. The second is a simple aggregation model, where we find that the whole is equal to the sum of its parts. This ontological grounding is simple and yields significant knowledge and scientific results. However, its reliance on duality and its general simplicity raise questions about its appropriateness for social science inquiry. These questions bring the more complicated reflexive reality into view. While it provides a realistic description of the relationship between people and their institutions, it is also infinitely complex and raises difficult questions about how knowledge can be derived about such a reality. Therefore, we now turn to our theories of knowledge, so that we can carefully weigh the costs and benefits of what is gained and lost as we commit to a specific meta-theoretical grounding.