40.2 – Labor Productivity and Income, Post-WWII

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Analyze the relationship between labor productivity and compensation in the U.S. after World War II

- Explain the tautological reasoning of the marginal productivity theory of distribution

According to orthodox economic theory, the firm’s decision to hire a worker is based on the same principle of comparing marginal cost and marginal benefit as its decision about how much to produce. When it comes to hiring workers, the marginal cost is the wage the firm will have to pay that worker, while the marginal benefit is the revenue the firm will earn when it sells the additional output (the ‘marginal product’) that worker produces. Like with the utility-maximizing consumer comparing marginal utilities for products (see chapter [Consumer choices]), profit maximizing firms comparing marginal products and wages gives us our demand curves in labor markets. The conclusion is that workers will be hired so long as they contribute at least as much as they cost; and in the end, people are paid according to their productivity (how much value they contribute ultimately to consumers). As elsewhere in orthodox theory, all of this only holds if these markets are competitive.

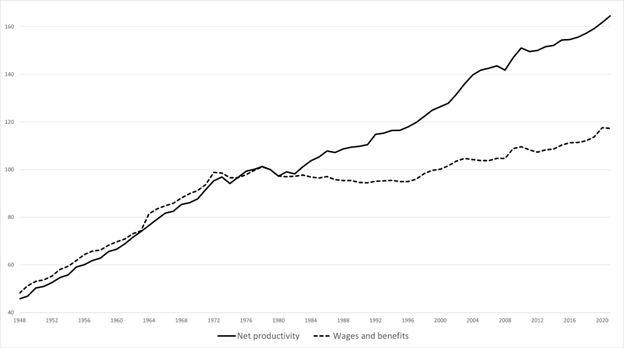

But, let’s look at the evidence. As Figure 1 below demonstrates, from the end of World War II to the early 1970s, wages did indeed increase almost exactly in step with gains in productivity–precisely what the marginal productivity theory of distribution predicts. Yet, in the mid- to late-1970s these two began to diverge, with productivity continuing to rise while hourly compensation (for non-supervisory workers) stagnating. A host of reasons contribute to these trends, but competitiveness of labor markets is most assuredly not one of them. In fact, unions were strongest, and therefore labor markets least competitive on the supply side, when the orthodox theory looked to be working.

In point of fact, research indicates that wage rates are of minor importance to hiring decisions–surveys of hiring managers simply do not suggest that the marginal cost of labor is a top concern for employers, though there are exceptions. More starkly, marginal product (the additional output one additional worker would produce, all else equal) is not important at all–in fact, it’s generally not even calculable. This suggests that demand curves don’t actually exist in labor markets; and, of course, without both supply and demand, the market model is not very useful.

The double tautology

Students of economics might wonder why so much of orthodox economic theory has been shown empirically to not reflect the real world of business and work accurately, and yet it persists as accepted theory. One way to understand this is in terms of the ‘as if’ methodology of orthodoxy explained in chapter “Choice in a World of Scarcity“. There, you saw the argument that an economic theory need not be realistic. Instead, we can simply model economic agents–firms, workers, consumers, and so on–as if they behaved in the optimizing fashion orthodox theory assumes.

In truth, the really big conclusions of orthodox theory, about why firms produce the products they produce, about why consumers consume what they do, about how much one item costs at the store versus another, about why CEOs are paid as much as they are–all of these are essentially tautologies. A tautology is saying the same thing twice and suggesting that the two statements prove each other. An orthodox economist, for instance, might argue that Karol purchased tea instead of coffee because Karol is maximizing her utility and tea gives her more utility. How do we know tea gives Karol more utility than coffee? Because she bought the tea. In brief, the consumer buys the things that give her more utility (per dollar) and the things that give her more utility are the things that she buys. What argument could be more true, yet less helpful?

The marginal productivity theory of distribution works much the same way, but with a string of two tautologies. The argument can be summarized like this: a consumer wouldn’t give a business more money than the utility she’s going to get from the product she’s buying from the business. Therefore, the business’ revenues reflect the value (utility) they create for consumers. The business, in turn, wouldn’t pay a worker (or CEO, or investor, or what have you) more than the value of the output they produce (that value, again, represents utility to the consumer). Hence, any given worker is paid, ultimately, according to the utility they produced for the consumer–and since society is made up of consumers, the worker’s income reflects their contribution to society. How do we know that paycheck is commensurate with social contribution? Because that’s how much society paid them!

The next section will offer an alternative, heterodox way of looking at the general subject of who gets paid how much and why–one that doesn’t require reference to the orthodox concepts that don’t seem to matter much, if at all, to most actual businesses.