40.4 – Understanding Class Distinctions Today

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define bifurcated labor markets

- Explain the rise in CEO compensation in terms of changing class affiliations

The traditional distinctions between workers, business owners, and rentiers discussed in the previous section may have inspired some questions in your mind, especially when you try to apply this system of classification (no pun intended) to the world around you. For instance, the aircraft mechanic who owns her own tools–is she a worker or a capitalist? After all, she owns the means of production; and yet, she works for a wage. And what about the manager who owns no part of the corporation he works for, yet makes his living, first and foremost, by his decisions about how the business’ assets will be used and how the product will be sold? Is he a worker or a capitalist?

Heterodox economists offer a wide and diverse array of answers to these questions, but the essence of the argument is the same: it is useful to understand the economy in terms of (1) groups of people making their money in different ways, and (2) the relationships of power between these groups.

Going further, in a class-based approach, who gets paid how much and why is ultimately a matter of which class is dominant, not just in the economic sense, but also in the broader social and political sense. Take for instance the notion of bifurcated labor markets, in which some workers enjoy high pay, opportunities for promotions, and job security, while other workers have low pay, little opportunity for advancement, and low job security. Some heterodox economists would explain this by referring to the notion of the technostructure. As chapter “The Megacorp” explains, the technostructure is the body of employees within the large corporation who have unique and important skills necessary for the long-run planning of the business enterprise.

Now consider the power relationships between the skilled employees in management, marketing, and so on, relative to the lower-skilled, ‘front-line’ workers. Within an individual corporation, it is the skilled workers who not only have authority over their subordinates, but more generally define the sorts of work the front-line workers will be doing in the first place. In this manner, the skilled ‘technostructure’ can create and maintain the distinctions between themselves and the unskilled front line. Given this dominance of one class over another, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the dominant class is paid better and has more job security.

Here, we’ve zoomed in to the more granular distinctions between workers inside the corporation itself. But notice that once we’ve moved to a class-based analysis we leave the strict confines of economic analysis and begin to look at the social, historical, and political characteristics of our topic as well. Let’s go forward now with a bit more history, looking ultimately for an explanation of why corporate executives are paid so much.

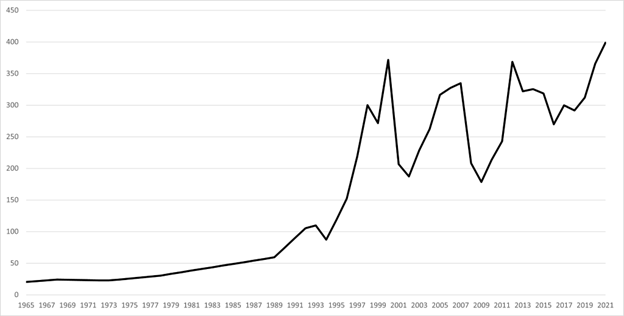

Economist Hyman Minksy described the shifts in the structure of developed capitalist economies from the 1970s to the present as a transition from managerial capitalism to money manager capitalism (that is, a form of capitalism in which financial firms and their interests take highest priority). You may recall the bailout of the dominant financial firms (that is, the money managers) during and after the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. But money manager capitalism refers to the dominance of not only the money managers themselves but also their interests and methods–that is, how they make their money. This is perhaps most clearly reflected in how the top management at non-financial corporations are paid: chiefly in stock options rather than traditional salary and benefits (see chapter “The Surplus and the Price Level”). And as a consequence of this there has been a massive divergence between the average worker’s pay and CEO compensation, as shown below.

Notice in figure 1 that in the 1960s and 70s, the era of managerial capitalism, CEOs typically made somewhere between 20 and 40 times as much as the average (not the lowest-paid) worker in their industry. As the U.S. economy transitioned into money manager capitalism in the 1980s, however, that ratio began to rise. Since the late 1990s, the average CEO of a large American corporation has made between about 200 and 400 times as much as the average worker. That’s roughly an order of magnitude (or a 1000%) increase over the era of managerial capitalism.

But, you probably noticed as well that the period of higher CEO pay ratios has also seen significantly more variation year-to-year than in the days of managerial capitalism. You might have guessed why this is: CEO pay in the latter period reflects primarily stock-based compensation. So when the stock market is booming, CEO pay rises rapidly, then falling in the bear markets (but never back to the levels of the 1960s and 70s) before rising again when the markets turn bullish again.

All of this is to suggest that CEOs and other top executives (the ‘C-suite’) have come to more closely resemble the rentier class since, roughly, the 1980s. Their incomes flow primarily from financial sector gains (selling stock, collecting dividends) rather than using the means of production to produce a product, or to some extent even managing the company well in any way other than maintaining a rising stock price. C-suite executives in the U.S., then, are being paid more now relative to workers, first, because they are more closely aligned with the financial sector, and second, because finance has broadly become more dominant in the economic system.

Notice, again, that the theory laid out above about CEO incomes doesn’t make any reference to marginal products, supply and demand in labor markets, or the other orthodox economic concepts. Instead, we’ve constructed an explanation that relies on notions of class embedded in a historical narrative. This is the essence of the heterodox approach to the subject.

a situation in which some workers enjoy high pay, opportunities for promotions, and job security, while other workers have low pay, little opportunity for advancement, and low job security