19.3 – How Government Borrowing Affects Investment and the Trade Balance

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the national saving and investment identity in terms of demand and supply

- Evaluate the role of budget surpluses and trade surpluses in national saving and investment identity

When governments are borrowers in financial markets, there are three possible sources for the funds from a macroeconomic point of view: (1) households might save more; (2) private firms might borrow less; and (3) the additional funds for government borrowing might come from outside the country, from foreign financial investors. Let’s begin with a review of why one of these three options must occur, and then explore how interest rates and exchange rates adjust to these connections.

The National Saving and Investment Identity

The national saving and investment identity, which we first introduced in The International Trade and Capital Flows chapter, provides a framework for showing the relationships between the sources of demand and supply in financial capital markets. The identity begins with a statement that must always hold true: the quantity of financial capital supplied in the market must equal the quantity of financial capital demanded.

Recall that, orthodox economists hold that savings are ultimately loaned out, to businesses for investment, families for houses, and so forth. In this perspective, the U.S. economy has two main sources for financial capital: private savings from inside the U.S. economy and public savings.

[latex]\text{Total savings = Private savings (S) + Public savings (T - G)}[/latex]

Governments often spend more than they receive in taxes and, therefore, public savings (T – G) is negative. This causes a need to borrow money in the amount of (G – T) instead of adding to the nation’s savings. If this is the case, we can view governments as demanders of financial capital instead of suppliers. In algebraic terms, we can rewrite the national savings and investment identity like this:

Let’s call this equation 2. We must accompany a change in any part of the national saving and investment identity by offsetting changes in at least one other part of the equation because we assume that the equality of quantity supplied and quantity demanded always holds. If the government budget deficit changes, then either private saving or investment or the trade balance—or some combination of the three—must change as well. Figure 1 shows the possible effects.

What about Budget Surpluses and Trade Surpluses?

The national saving and investment identity must always hold true because, by definition, the quantity supplied and quantity demanded in the financial capital market must always be equal. However, the formula will look somewhat different if the government budget is in deficit rather than surplus or if the balance of trade is in surplus rather than deficit. For example, in 1999 and 2000, the U.S. government had budget surpluses, although the economy was still experiencing trade deficits. When the government was running budget surpluses, it was acting as a saver rather than a borrower, and supplying rather than demanding financial capital. As a result, we would write the national saving and investment identity during this time as:

Let's call this equation 3. Notice that this expression is mathematically the same as equation 2 except the savings and investment sides of the identity have simply flipped sides.

During the 1960s, the U.S. government was often running a budget deficit, but the economy was typically running trade surpluses. Since a trade surplus means that an economy is experiencing a net outflow of financial capital, we would write the national saving and investment identity as:

Instead of the balance of trade representing part of the supply of financial capital, which occurs with a trade deficit, a trade surplus represents an outflow of financial capital leaving the domestic economy and invested elsewhere in the world.

We assume that the point to these equations is that the national saving and investment identity always hold. When you write these relationships, it is important to engage your brain and think about what is on the supply and demand side of the financial capital market before you start your calculations.

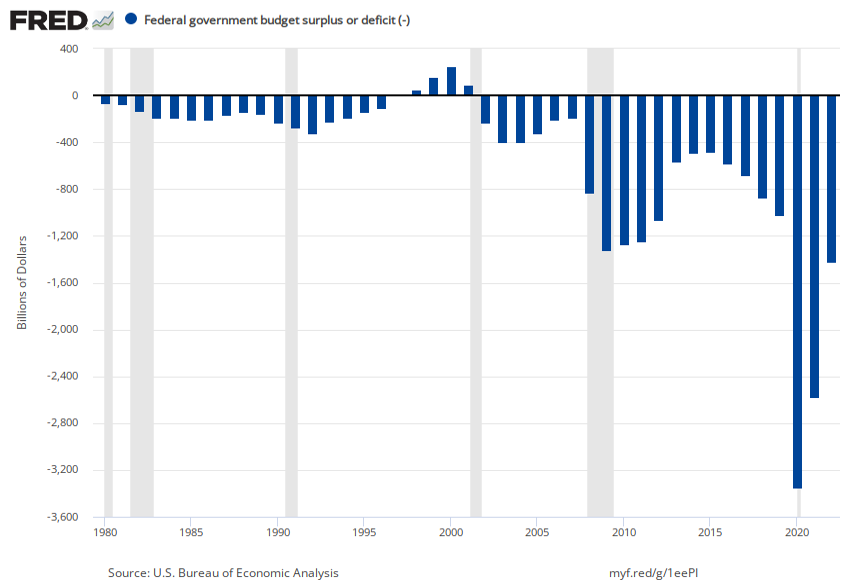

As you can see in Figure 2, the Office of Management and Budget shows that the United States has consistently run budget deficits since 1977, with the exception of the late 1990s. What is alarming to some is the dramatic increase in budget deficits that has occurred since 2008, which in part reflects declining tax revenues and increased safety net expenditures due to the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. (Recall that T is net taxes. When the government must transfer funds back to individuals for safety net expenditures like Social Security and unemployment benefits, budget deficits rise.) These deficits may have implications for the future health of the U.S. economy. (Note, though, that the increases in government deficits shown here must be understood in the context of a growing economy as a whole. As a percentage of GDP, these deficits have still increased over time, but much less dramatically.)

Figure 2. United States Budget Surplus and Deficit, 1979–present. The United States has run a budget deficit for over 30 years, with the exception of the late 1990s. Military expenditures, entitlement programs, and the decrease in tax revenue coupled with increased safety net support during the Great Recession and COVID-19 pandemic are major contributors to the dramatic increases in the deficit after 2008.

A rising budget deficit may result in a fall in domestic investment, a rise in private savings, or a rise in the trade deficit. The following modules discuss each of these possible effects in more detail.

Summary

A change in any part of the national saving and investment identity suggests that if the government budget deficit changes, then either private savings, private investment in physical capital, or the trade balance—or some combination of the three—must change as well.

the international flows of money that facilitates trade and investment