9.2 – Measuring Trade Balances

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain merchandise trade balance, current account balance, and unilateral transfers

- Identify components of the U.S. current account balance

- Calculate the merchandise trade balance and current account balance using import and export data for a country

A few decades ago, it was common to track the solid or physical items that planes, trains, and trucks transported between countries as a way of measuring the balance of trade. Economists call this measurement is called the merchandise trade balance. In most high-income economies, including the United States, goods comprise less than half of a country’s total production, while services comprise more than half. The last two decades have seen a surge in international trade in services, powered by technological advances in telecommunications and computers that have made it possible to export or import customer services, finance, law, advertising, management consulting, software, construction engineering, and product design. Most global trade still takes the form of goods rather than services, and the government announces and the media prominently report the merchandise trade balance. Old habits are hard to break. Economists, however, typically rely on broader measures such as the balance of trade or the current account balance which includes other international flows of income and foreign aid.

Components of the U.S. Current Account Balance

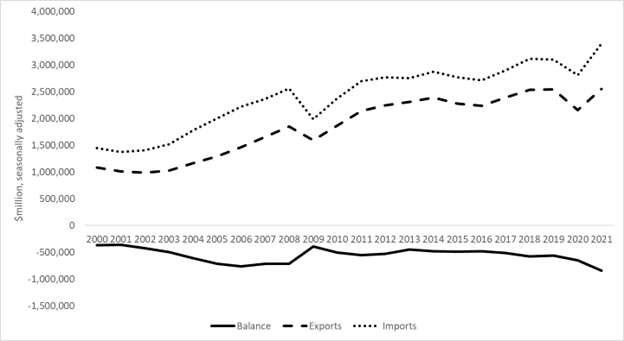

The chart below shows the main components of U.S. trade. Because imports exceed exports, the trade balance is negative, showing a trade deficit.

Table 1 breaks down the four main components of the U.S. current account balance for the last quarter of 2015 (seasonally adjusted). The first line shows the merchandise trade balance; that is, exports and imports of goods. Because imports exceed exports, the trade balance in the final column is negative, showing a merchandise trade deficit. We can explain how the government collects this trade information in the following Clear It Up feature.

| Value of Exports (money flowing into the United States) | Value of Imports (money flowing out of the United States) | Balance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goods | $410.0 | $595.5 | –$185.3 |

| Services | $180.4 | $122.3 | $58.1 |

| Income receipts and payments | $203.0 | $152.4 | $50.6 |

| Unilateral transfers | $27.3 | $64.4 | –$37.1 |

| Current account balance | $820.7 | $934.4 | –$113.7 |

How does the U.S. government collect trade statistics?

Do not confuse the balance of trade (which tracks imports and exports), with the current account balance, which includes not just exports and imports, but also income from investment and transfers.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) within the U.S. Department of Commerce compiles statistics on the balance of trade using a variety of different sources. Merchandise importers and exporters must file monthly documents with the Census Bureau, which provides the basic data for tracking trade. To measure international trade in services—which can happen over a telephone line or computer network without shipping any physical goods—the BEA carries out a set of surveys. Another set of BEA surveys tracks investment flows, and there are even specific surveys to collect travel information from U.S. residents visiting Canada and Mexico. For measuring unilateral transfers, the BEA has access to official U.S. government spending on aid, and then also carries out a survey of charitable organizations that make foreign donations.

The BEA then cross-checks this information on international flows of goods and capital against other available data. For example, the Census Bureau also collects data from the shipping industry, which it can use to check the data on trade in goods. All companies involved in international flows of capital—including banks and companies making financial investments like stocks—must file reports, which the U.S. Department of the Treasury ultimately checks. The BEA also can cross check information on foreign trade by looking at data collected by other countries on their foreign trade with the United States, and also at the data collected by various international organizations. Take these data sources, stir carefully, and you have the U.S. balance of trade statistics. Much of the statistics that we cite in this chapter come from these sources.

The second row of Table 1 provides data on trade in services. Here, the U.S. economy is running a surplus. Although the level of trade in services is still relatively small compared to trade in goods, the importance of services has expanded substantially over the last few decades. For example, U.S. exports of services were equal to about one-half of U.S. exports of goods in 2015, compared to one-fifth in 1980.

The third component of the current account balance, labeled "income payments," refers to money that U.S. financial investors received on their foreign investments (money flowing into the United States) and payments to foreign investors who had invested their funds here (money flowing out of the United States). The reason for including this money on foreign investment in the overall measure of trade, along with goods and services, is that, from an economic perspective, income is just as much an economic transaction as car, wheat, or oil shipments: it is just trade that is happening in the financial capital market.

The final category of the current account balance is unilateral transfers, which are payments that government, private charities, or individuals make in which they send money abroad without receiving any direct good or service. Economic or military assistance from the U.S. government to other countries fits into this category, as does spending abroad by charities to address poverty or social inequalities. When an individual in the United States sends money overseas, as is the case with some immigrants, it is also counted in this category. The current account balance treats these unilateral payments like imports, because they also involve a stream of payments leaving the country. For the U.S. economy, unilateral transfers are almost always negative. This pattern, however, does not always hold. In 1991, for example, when the United States led an international coalition against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the Gulf War, many other nations agreed that they would make payments to the United States to offset the U.S. war expenses. These payments were large enough that, in 1991, the overall U.S. balance on unilateral transfers was a positive $10 billion.

The following Work It Out feature steps you through the process of using the values for goods, services, and income payments to calculate the merchandise balance and the current account balance.

Calculating the Merchandise Balance and the Current Account Balance

| Exports (in $ billions) | Imports (in $ billions) | Balance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goods | |||

| Services | |||

| Income payments | |||

| Unilateral transfers | |||

| Current account balance |

Use the information given below to fill in Table 2, and then calculate:

- The merchandise balance

- The current account balance

Known information:

- Unilateral transfers: $130

- Exports in goods: $1,046

- Exports in services: $509

- Imports in goods: $1,562

- Imports in services: $371

- Income received by U.S. investors on foreign stocks and bonds: $561

- Income received by foreign investors on U.S. assets: $472

Step 1. Focus on goods and services first. Enter the dollar amount of exports of both goods and services under the Export column.

Step 2. Enter imports of goods and services under the Import column.

Step 3. Under the Export column and in the row for Income payments, enter the financial flows of money coming back to the United States. U.S. investors are earning this income from abroad.

Step 4. Under the Import column and in the row for Income payments, enter the financial flows of money going out of the United States to foreign investors. Foreign investors are earning this money on U.S. assets, like stocks.

Step 5. Unilateral transfers are money flowing out of the United States in the form of, for example, military aid, foreign aid, and global charities. Because the money leaves the country, enter it under Imports and in the final column as well, as a negative.

Step 6. Calculate the trade balance by subtracting imports from exports in both goods and services. Enter this in the final Balance column. This can be positive or negative.

Step 7. Subtract the income payments flowing out of the country (under Imports) from the money coming back to the United States (under Exports) and enter this amount under the Balance column.

Step 8. Enter unilateral transfers as a negative amount under the Balance column.

Step 9. The merchandise trade balance is the difference between exports of goods and imports of goods—the first number under Balance.

Step 10. Now sum up your columns for Exports, Imports, and Balance. The final balance number is the current account balance.

The merchandise balance of trade is the difference between exports and imports. In this case, it is equal to $1,046 – $1,562, a trade deficit of –$516 billion. The current account balance is –$419 billion. See the completed Table 3.

| Value of Exports (money flowing into the United States) | Value of Imports (money flowing out of the United States) | Balance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goods | $1,510.3 | $2,272.9 | –$762.6 |

| Services | $750.9 | $488.7 | $262.2 |

| Income receipts and payments | $782.9 | $600.5 | $182.4 |

| Unilateral transfers | $128.6 | $273.6 | –$145.0 |

| Current account balance | $3,172.7 | $3,635.7 | –$463.0 |

Summary

The trade balance measures the gap between a country’s exports and its imports. In most high-income economies, goods comprise less than half of a country’s total production, while services comprise more than half. The last two decades have seen a surge in international trade in services; however, most global trade still takes the form of goods rather than services. The current account balance includes the trade in goods, services, and money flowing into and out of a country from investments and unilateral transfers.

References

Central Intelligence Agency. "The World Factbook." Last modified October 31, 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gm.html.

U.S. Department of Commerce. "Bureau of Economic Analysis." Last modified December 1, 2013. http://www.bea.gov/.

U.S. Department of Commerce. "United States Census Bureau." http://www.census.gov/.

Glossary

- balance of trade (trade balance)

- the gap, if any, between a nation’s exports and imports

- current account balance

- a broad measure of the balance of trade that includes trade in goods and services, as well as international flows of income and foreign aid

- merchandise trade balance

- the balance of trade looking only at goods

- unilateral transfers

- "one-way payments" that governments, private entities, or individuals make that they sent abroad with nothing received in return

the balance of trade looking only at goods

a broad measure of the balance of trade that includes trade in goods and services, as well as international flows of income and foreign aid

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of studying neoclassical economics

- Explain the relationship between production and division of labor

- Evaluate the significance of scarcity in neoclassical economics

Orthodox (or Neoclassical) economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity. These can be individual decisions, family decisions, business decisions or societal decisions. If you look around carefully, you will see that scarcity is a fact of life. Scarcity means that human wants for goods, services and resources exceed what is available. Resources, such as labor, tools, land, and raw materials are necessary to produce the goods and services we want but they exist in limited supply. Of course, the ultimate scarce resource is time- everyone, rich or poor, has just 24 hours in the day to try to acquire the goods they want. At any point in time, there is only a finite amount of resources available.

Think about it this way: In 2015 the labor force in the United States contained over 158.6 million workers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Similarly, the total area of the United States is 3,794,101 square miles. These are large numbers for such crucial resources, however, they are limited. Because these resources are limited, so are the numbers of goods and services we produce with them. Combine this with the fact that human wants seem to be virtually infinite, and you can see why scarcity is a problem.

If you still do not believe that scarcity is a problem, consider the following: Does everyone need food to eat? Does everyone need a decent place to live? Does everyone have access to healthcare? In every country in the world, there are people who are hungry, homeless (for example, those who call park benches their beds, as shown in Figure 1), and in need of healthcare, just to focus on a few critical goods and services. Why is this the case? Orthodox economics believes that it is because of scarcity. Let’s delve into the orthodox economic concept of scarcity a little deeper, because it is crucial to understanding this perspective.

The Orthodox Economic Problem of Scarcity

Think about all the things you consume: food, shelter, clothing, transportation, healthcare, and entertainment. How do you acquire those items? You do not produce them yourself. You buy them. How do you afford the things you buy? You work for pay. Or if you do not, someone else does on your behalf. Yet most of us never have enough to buy all the things we want. This is because of scarcity. So how do we solve it?

Every society, at every level, must make choices about how to use its resources. Families must decide whether to spend their money on a new car or a fancy vacation. Towns must choose whether to put more of the budget into police and fire protection or into the school system. Nations must decide whether to devote more funds to national defense or to protecting the environment. In most cases, there just isn’t enough money in the budget to do everything. So why do we not each just produce all of the things we consume? The simple answer is most of us do not know how, but that is not the main reason. Think back to pioneer days, when individuals knew how to do so much more than we do today, from building their homes, to growing their crops, to hunting for food, to repairing their equipment. Most of us do not know how to do all—or any—of those things. It is not because we could not learn. Rather, we do not have to. The reason why is something called the division and specialization of labor, an idea first put forth by Adam Smith, Figure 2, in his book, The Wealth of Nations.

The Division of and Specialization of Labor

The formal study of economics began when Adam Smith (1723–1790) published his famous book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Many authors had written on economics in the centuries before Smith, but he was (at least, among) the first to comprehensively address the functioning of a capitalist market economy. In the first chapter, Smith introduces the division of labor, which means that the way a good or service is produced is divided into a number of tasks that are performed by different workers, instead of all the tasks being done by the same person.

To illustrate the division of labor, Smith counted how many tasks went into making a pin: drawing out a piece of wire, cutting it to the right length, straightening it, putting a head on one end and a point on the other, and packaging pins for sale, to name just a few. Smith counted 18 distinct tasks that were often done by different people—all for a pin, believe it or not!

Modern businesses divide tasks as well. Even a relatively simple business like a restaurant divides up the task of serving meals into a range of jobs like top chef, sous chefs, less-skilled kitchen help, servers to wait on the tables, a greeter at the door, janitors to clean up, and a business manager to handle paychecks and bills—not to mention the economic connections a restaurant has with suppliers of food, furniture, kitchen equipment, and the building where it is located. A complex business like a large manufacturing factory, such as the shoe factory shown in Figure 3, or a hospital can have hundreds of job classifications.

Why the Division of Labor Increases Production

When the tasks involved with producing a good or service are divided and subdivided, workers and businesses can produce a greater quantity of output. In his observations of pin factories, Smith observed that one worker alone might make 20 pins in a day, but that a small business of 10 workers (some of whom would need to do two or three of the 18 tasks involved with pin-making), could make 48,000 pins in a day. How can a group of workers, each specializing in certain tasks, produce so much more than the same number of workers who try to produce the entire good or service by themselves? Smith offered three reasons.

First, specialization in a particular small job allows workers to focus on specific parts of the production process which allows workers to focus on learning a limited number of tasks and to improve at performing those tasks. This pattern holds true for many workers, including assembly line laborers who build cars, stylists who cut hair, and doctors who perform heart surgery.A similar pattern often operates within businesses. In many cases, a business that focuses on one or a few products (sometimes called its “core competency”) is more successful than firms that try to make a wide range of products. Whatever the reason, specialization in production improves productivity more than if producers attempt a combination of tasks.

Second, specialization limits distractions and the loss of time associated with transitioning from one type of work to another. If a worker is responsible for one task and is then asked to do another task, it will take that worker time to adjust to the new task. Productivity that otherwise would have been generated by having a worker perform only one task will be lost as the worker transitions to another task.

Third, specialized workers often know their jobs well enough to suggest innovative ways to do their work faster and better. Frequently this means that workers improve upon the ways in which they use the tools, machines, and equipment associated with their work.

The ultimate result of workers who can focus on their preferences and talents, learn to do their specialized jobs better, and work in larger organizations is that society as a whole can produce and consume far more than if each person tried to produce all of their own goods and services.

Trade and Markets

Specialization only makes sense, though, if workers can use the pay they receive for doing their jobs to purchase the other goods and services that they need. In short, specialization requires trade.

You do not have to know anything about electronics or sound systems to play music—you just buy an iPod or MP3 player, download the music and listen. You do not have to know anything about artificial fibers or the construction of sewing machines if you need a jacket—you just buy the jacket and wear it. You do not need to know anything about internal combustion engines to operate a car—you just get in and drive. Instead of trying to acquire all the knowledge and skills involved in producing all of the goods and services that you wish to consume, the market allows you to learn a specialized set of skills and then use the pay you receive to buy the goods and services you need or want. This is how our modern society has evolved into a strong economy.

Why Study Economics?

Now that we have gotten an overview on what economics studies, let’s quickly discuss why you are right to study it. Economics is not primarily a collection of facts to be memorized, though there are plenty of important concepts to be learned. Instead, economics is better thought of as a collection of questions to be answered or puzzles to be worked out. Most important, economics provides the tools to work out those puzzles. If you have yet to be been bitten by the economics “bug,” there are other reasons why you should study economics.

- Virtually every major problem facing the world today, from global warming, to world poverty, to the conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia, has an economic dimension. If you are going to be part of solving those problems, you need to be able to understand them. Economics is crucial.

- It is hard to overstate the importance of economics to good citizenship. You need to be able to vote intelligently on budgets, regulations, and laws in general. When the U.S. government came close to a standstill at the end of 2012 due to the “fiscal cliff,” what were the issues involved? Did you know?

- A basic understanding of economics makes you a well-rounded thinker. When you read articles about economic issues, you will understand and be able to evaluate the writer’s argument. When you hear classmates, co-workers, or political candidates talking about economics, you will be able to distinguish between common sense and nonsense. You will find new ways of thinking about current events and about personal and business decisions, as well as current events and politics.

The study of economics does not dictate the answers, but it can illuminate the different choices.

Summary

Economics seeks to solve the problem of scarcity, which is when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply. A modern economy displays a division of labor, in which people earn income by specializing in what they produce and then use that income to purchase the products they need or want. The division of labor allows individuals and firms to specialize and to produce more for several reasons: a) It allows the agents to focus on areas of advantage due to natural factors and skill levels; b) It encourages the agents to learn and invent; c) It allows agents to take advantage of economies of scale. Division and specialization of labor only work when individuals can purchase what they do not produce in markets. Learning about economics helps you understand the major problems facing the world today, prepares you to be a good citizen, and helps you become a well-rounded thinker.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2015. “The Employment Situation—February 2015.” Accessed March 27, 2015. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

Williamson, Lisa. “US Labor Market in 2012.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed December 1, 2013. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/03/art1full.pdf.

Glossary

division of labor

the way in which the work required to produce a good or service is divided into tasks performed by different workers

economics (orthodox definition)

the study of how humans make choices under conditions of scarcity

economies of scale

when the average cost of producing each individual unit declines as total output increases

scarcity

when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply

specialization

when workers or firms focus on particular tasks for which they are well-suited within the overall production process

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of studying neoclassical economics

- Explain the relationship between production and division of labor

- Evaluate the significance of scarcity in neoclassical economics

Orthodox (or neoclassical) economics is the study of how humans make decisions in the face of scarcity. These can be individual decisions, family decisions, business decisions or societal decisions. If you look around carefully, you will see that scarcity is a fact of life. Scarcity means that human wants for goods, services and resources exceed what is available. Resources, such as labor, tools, land, and raw materials are necessary to produce the goods and services we want but they exist in limited supply. Of course, the ultimate scarce resource is time- everyone, rich or poor, has just 24 hours in the day to try to acquire the goods they want. At any point in time, there is only a finite amount of resources available.

Think about it this way: In 2015 the labor force in the United States contained over 158.6 million workers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Similarly, the total area of the United States is 3,794,101 square miles. These are large numbers for such crucial resources, however, they are limited. Because these resources are limited, so are the numbers of goods and services we produce with them. Combine this with the fact that human wants seem to be virtually infinite, and you can see why scarcity is a problem.

If you still do not believe that scarcity is a problem, consider the following: Does everyone need food to eat? Does everyone need a decent place to live? Does everyone have access to healthcare? In every country in the world, there are people who are hungry, homeless (for example, those who call park benches their beds, as shown in Figure 1), and in need of healthcare, just to focus on a few critical goods and services. Why is this the case? Orthodox economics believes that it is because of scarcity. Let’s delve into the orthodox economic concept of scarcity a little deeper, because it is crucial to understanding this perspective.

The Orthodox Economic Problem of Scarcity

Think about all the things you consume: food, shelter, clothing, transportation, healthcare, and entertainment. How do you acquire those items? You do not produce them yourself. You buy them. How do you afford the things you buy? You work for pay. Or if you do not, someone else does on your behalf. Yet most of us never have enough to buy all the things we want. This is because of scarcity. So how do we solve it?

Every society, at every level, must make choices about how to use its resources. Families must decide whether to spend their money on a new car or a fancy vacation. Towns must choose whether to put more of the budget into police and fire protection or into the school system. Nations must decide whether to devote more funds to national defense or to protecting the environment. In most cases, there just isn’t enough money in the budget to do everything. So why do we not each just produce all of the things we consume? The simple answer is most of us do not know how, but that is not the main reason. Think back to pioneer days, when individuals knew how to do so much more than we do today, from building their homes, to growing their crops, to hunting for food, to repairing their equipment. Most of us do not know how to do all—or any—of those things. It is not because we could not learn. Rather, we do not have to. The reason why is something called the division and specialization of labor, an idea first put forth by Adam Smith, Figure 2, in his book, The Wealth of Nations.

The Division of and Specialization of Labor

The formal study of economics began when Adam Smith (1723–1790) published his famous book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Many authors had written on economics in the centuries before Smith, but he was (at least, among) the first to comprehensively address the functioning of a capitalist market economy. In the first chapter, Smith introduces the division of labor, which means that the way a good or service is produced is divided into a number of tasks that are performed by different workers, instead of all the tasks being done by the same person.

To illustrate the division of labor, Smith counted how many tasks went into making a pin: drawing out a piece of wire, cutting it to the right length, straightening it, putting a head on one end and a point on the other, and packaging pins for sale, to name just a few. Smith counted 18 distinct tasks that were often done by different people—all for a pin, believe it or not!

Modern businesses divide tasks as well. Even a relatively simple business like a restaurant divides up the task of serving meals into a range of jobs like top chef, sous chefs, less-skilled kitchen help, servers to wait on the tables, a greeter at the door, janitors to clean up, and a business manager to handle paychecks and bills—not to mention the economic connections a restaurant has with suppliers of food, furniture, kitchen equipment, and the building where it is located. A complex business like a large manufacturing factory, such as the shoe factory shown in Figure 3, or a hospital can have hundreds of job classifications.

Why the Division of Labor Increases Production

When the tasks involved with producing a good or service are divided and subdivided, workers and businesses can produce a greater quantity of output. In his observations of pin factories, Smith observed that one worker alone might make 20 pins in a day, but that a small business of 10 workers (some of whom would need to do two or three of the 18 tasks involved with pin-making), could make 48,000 pins in a day. How can a group of workers, each specializing in certain tasks, produce so much more than the same number of workers who try to produce the entire good or service by themselves? Smith offered three reasons.

First, specialization in a particular small job allows workers to focus on specific parts of the production process which allows workers to focus on learning a limited number of tasks and to improve at performing those tasks. This pattern holds true for many workers, including assembly line laborers who build cars, stylists who cut hair, and doctors who perform heart surgery.A similar pattern often operates within businesses. In many cases, a business that focuses on one or a few products (sometimes called its “core competency”) is more successful than firms that try to make a wide range of products. Whatever the reason, specialization in production improves productivity more than if producers attempt a combination of tasks.

Second, specialization limits distractions and the loss of time associated with transitioning from one type of work to another. If a worker is responsible for one task and is then asked to do another task, it will take that worker time to adjust to the new task. Productivity that otherwise would have been generated by having a worker perform only one task will be lost as the worker transitions to another task.

Third, specialized workers often know their jobs well enough to suggest innovative ways to do their work faster and better. Frequently this means that workers improve upon the ways in which they use the tools, machines, and equipment associated with their work.

The ultimate result of workers who can focus on their preferences and talents, learn to do their specialized jobs better, and work in larger organizations is that society as a whole can produce and consume far more than if each person tried to produce all of their own goods and services.

Trade and Markets

Specialization only makes sense, though, if workers can use the pay they receive for doing their jobs to purchase the other goods and services that they need. In short, specialization requires trade.

You do not have to know anything about electronics or sound systems to play music—you just buy an iPod or MP3 player, download the music and listen. You do not have to know anything about artificial fibers or the construction of sewing machines if you need a jacket—you just buy the jacket and wear it. You do not need to know anything about internal combustion engines to operate a car—you just get in and drive. Instead of trying to acquire all the knowledge and skills involved in producing all of the goods and services that you wish to consume, the market allows you to learn a specialized set of skills and then use the pay you receive to buy the goods and services you need or want. This is how our modern society has evolved into a strong economy.

Why Study Economics?

Now that we have gotten an overview on what economics studies, let’s quickly discuss why you are right to study it. Economics is not primarily a collection of facts to be memorized, though there are plenty of important concepts to be learned. Instead, economics is better thought of as a collection of questions to be answered or puzzles to be worked out. Most important, economics provides the tools to work out those puzzles. If you have yet to be been bitten by the economics “bug,” there are other reasons why you should study economics.

- Virtually every major problem facing the world today, from global warming, to world poverty, to the conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia, has an economic dimension. If you are going to be part of solving those problems, you need to be able to understand them. Economics is crucial.

- It is hard to overstate the importance of economics to good citizenship. You need to be able to vote intelligently on budgets, regulations, and laws in general. When the U.S. government came close to a standstill at the end of 2012 due to the “fiscal cliff,” what were the issues involved? Did you know?

- A basic understanding of economics makes you a well-rounded thinker. When you read articles about economic issues, you will understand and be able to evaluate the writer’s argument. When you hear classmates, co-workers, or political candidates talking about economics, you will be able to distinguish between common sense and nonsense. You will find new ways of thinking about current events and about personal and business decisions, as well as current events and politics.

The study of economics does not dictate the answers, but it can illuminate the different choices.

Summary

Economics seeks to solve the problem of scarcity, which is when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply. A modern economy displays a division of labor, in which people earn income by specializing in what they produce and then use that income to purchase the products they need or want. The division of labor allows individuals and firms to specialize and to produce more for several reasons: a) It allows the agents to focus on areas of advantage due to natural factors and skill levels; b) It encourages the agents to learn and invent; c) It allows agents to take advantage of economies of scale. Division and specialization of labor only work when individuals can purchase what they do not produce in markets. Learning about economics helps you understand the major problems facing the world today, prepares you to be a good citizen, and helps you become a well-rounded thinker.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2015. “The Employment Situation—February 2015.” Accessed March 27, 2015. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

Williamson, Lisa. “US Labor Market in 2012.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed December 1, 2013. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/03/art1full.pdf.

Glossary

division of labor

the way in which the work required to produce a good or service is divided into tasks performed by different workers

economics (orthodox definition)

the study of how humans make choices under conditions of scarcity

economies of scale

when the average cost of producing each individual unit declines as total output increases

scarcity

when human wants for goods and services exceed the available supply

specialization

when workers or firms focus on particular tasks for which they are well-suited within the overall production process

exists when a nation's exports exceed its imports and it calculates them as exports – imports

"one-way payments" that governments, private entities, or individuals make that they sent abroad with nothing received in return