13.1 – Introduction to Macroeconomic Viability and the Corn Model

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn about:

- The Economy as a Going Concern

- A Brief History of the Surplus Approach to Value and Distribution

- The Corn Model: Simple Reproduction

- The Corn Model: Production with a Surplus

- A Corn Model Example

The Economy as a Going Concern

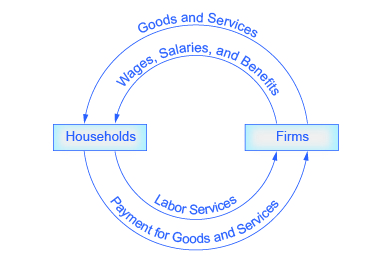

You may recall Figure 2 from Chapter 1, reproduced below.

Here we have a most basic model of a capitalist economy, with firms and households engaging in two types of transactions: firms sell goods and services to households in exchange for money, while households sell labor (and other productive inputs) to firms, also in exchange for money. One of the big questions economists try to answer, then, is “how much money?” That is, for what price is this or that product sold, or how much does a particular worker get paid, and why?

Orthodox economists argue that the prices, wages, and so on associated with the flow of goods, services, labor, capital, and all the rest are determined by the interaction of supply and demand. In turn, technology and individual skills determine the supply of goods and services and the demand for inputs, while households’ preferences determine the demand for goods and services and the supply of inputs.

In contrast, heterodox economists focus on how prices, wages, and the like are determined systematically, according to the technological input requirements of production, as well as through power struggles between organized groups–corporations, cartels, labor unions, governments, and so on. In the modern American economy, it is the first of these groups, the corporations, that tend to have the most power in these struggles, and therefore the most control over the determination of prices, wages, and other values. Chapter “The Megacorp” covers many of the important topics of corporate power from a microeconomic perspective. In this chapter we look at the big picture.

The first thing to notice about the figure above is its circular nature. This suggests that we ought to treat the economy it depicts as a going concern. A going concern is an organization that operates without a predetermined endpoint. A football game, for instance, is not a going concern. Everyone understands at the beginning that the game will end after one hour (for NFL games). And, even though the actual run time of the game will be longer, as the clock is stopped for penalties, timeouts, halftime, and so many other reasons, the game will always eventually be over when the clock in the fourth quarter goes to zero. A football franchise like the Seattle Seahawks, however, is a going concern. Even though players and coaches retire and get replaced, the team itself continues to exist. And although it is possible that the franchise will one day be dissolved, that day is not known and no one on the team is making decisions based on this unknown final day.

The economy is like a football franchise in this respect. The workers who built the St. Johns bridge, for instance, are no longer with us. Yet, the bridge still stands as new generations of workers have maintained it and continue to do so.

And the bridge is only a microscopic part of the U.S. economy, which in turn is only a small part of the world economy. When you look at these economies–at the national level or the global–it is clear that they continue to run even as one generation retires and the next is trained to take their place. And, of course, no one outside of doomsday groups seriously contemplates a known ‘end of the world’. All of which is to say, again, that economies meet the basic definition of a going concern.

The second thing to notice about the figure above is that the question of “how much money?”–that is, at what price is a product sold, or at what wage is a worker paid—is central to the flow of exchange over time. While prices are not necessarily so central to all types of economies, they surely are to capitalist ones. Rent, payrolls, debt, dividends, and so much else are all paid in sums of money. If a household’s paycheck isn’t large enough to pay the rent, its economic position is in jeopardy. Likewise, if a firm isn’t bringing in enough revenues to cover payroll or to maintain its production equipment, it risks potential bankruptcy.

But, when taking a macroeconomic perspective, the most important thing to realize is that all of these households and firms are connected. The household’s paycheck–money coming in–is part of the firm’s payroll–the same money, but going out of the firm. The household’s rent, in turn, is income to the landlord, who may be the customer of the firm, and so on and so on. This interconnectedness, coupled with the idea that the economy is a going concern, begs a crucial question: what prices, wages, and so on would allow an economy to continue to operate through time? Heterodox economists approach this question through the surplus approach and the corn model.