33.3 – Business Models, Plural: Aims and Methods of the Megacorp

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify different general methods by which businesses can pursue profits

- Analyze the nature and significance of advertising

- Apply heterodox concepts to the analysis of the pharmaceutical industry

As a professor of mine, James Sturgeon, is fond of saying, there’s more than one way to make money: You can…

- Steal

- Extort

- Accept a bribe

- Speculate on the financial or real estate markets

- Inherit

- Con

- Or, perhaps failing all of the above, you could earn it

For our purposes here, this can be interpreted as a rather cheeky way of saying that different businesses have different business models—that is, different ways of making money in a market (or several markets). And, while they might all be treated with the utmost abstraction as combining inputs to produce outputs of greater value, heterodox economists are inclined to believe that not every way of making money is the same.

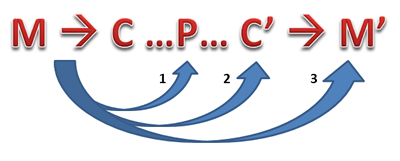

Breaking down all of the means by which modern businesses make money is far beyond the scope of this chapter. Instead, we’ll borrow from Karl Marx’s extensive work on how capitalist economies function to create a simplified picture, Figure 1, of what a business enterprise does. And from there, we’ll look to institutional economics to understand qualitative differences in how businesses generate their earnings.

In Figure 1, M represents an amount of money and C represents a commodity (for instance the lumber and other building materials a construction company may use to build a house). P represents the production process that converts the commodity C (building materials) into some other commodity C’ (a house) to be sold for some amount of money M’. This process can be treated as a shorthand depiction of what any business does, with the requirement that if the business is to remain in business M’ must be greater than M. It may be useful here to take a moment to review the chapter “Cost Assumptions for Profit Maximizing Firms,” specifically the definitions of firm and production therein. How does Figure 1 differ?

The difference may not be obvious, but it is important. In the neoclassical tradition in economics—indeed, in the classical tradition which Marx was critiquing—production by businesses is treated as a C→ C’ process. That is, all business activity is part of converting commodity inputs into commodity outputs which are of greater value, ultimately, to consumers. Clearly, Figure 1 is more than that: it treats money and commodities as distinct things. This allows us to look at the step-by-step process by which money is converted into commodities, production creates new commodities, and money is created by sale of those new commodities. The whole process of turning money into commodity inputs and ultimately selling commodity outputs for money we’ll call monetary production. The full implications of these distinctions for Marxian (or radical political) economics would require its own course. For now, we can use this shorthand description of how a business enterprise works to think about different types of business models.

The three numbered arrows in Figure 1 represent three different ways that managers, engineers, marketers, and others (the technostructure) within a business enterprise can influence the process of monetary production. The first arrow, following M to P, indicates something close to the traditional way of thinking of a business: money is invested into a production process that turns inputs into outputs for sale. This could include building a new factory or setting up a research and development (R&D) team to design new products or more efficient production practices. What is significant here is that the focus is on producing something—turning stuff C into stuff C’, presumably with the hope that people will be willing to pay more for C’ than was paid for the C necessary to produce it.

The second arrow indicates a different business model—that is, another way the monetary production process could be influenced to make money. Here, you will notice, the initial money invested is going not to production, P, but to the produced commodity, C’. This is meant to indicate investments made to change the perceived value of the product the business sells. Of course, one way to do this is to improve the product itself, which would be indicated by the first arrow. With arrow 2, however, we’re dealing with changing the perceived value of the product without actually changing the product itself; and you’ve probably already guessed the most salient way this can be done: advertising.

Here, the founder of institutional economics, Thorstein Veblen, is worth quoting at length:

The end sought by the systematic advertising of the larger business concerns is…a monopoly of custom and prestige.… The great end of consistent advertising is to establish such differential monopolies resting on popular conviction…. The cost, as well as the pecuniary value and the magnitude, of this organized fabrication of popular convictions is indicated by such statements as that the proprietors of a certain well-known household remedy, reputed among medical authorities to be of entirely dubious value, have for a series of years found their profits in spending several million dollars annually in advertisements. This case is by no means unique.

It has been said, no doubt in good faith and certainly with some reason, that advertising as currently carried on gives the body of consumers valuable information and guidance as to the ways and means whereby their wants can be satisfied and their purchasing power can be best utilized. To the extent to which this holds true, advertising is a service to the community. But there is a large reservation to be made on this head. Advertising is competitive; the greater part of it aims to divert purchases, etc., from one channel to another channel of the same general class. And to the extent to which the efforts of advertising in all its branches are spent on this competitive disturbance of trade, they are, on the whole, of slight if any immediate service to the community. (Veblen 1904, pp. 55-7, emphasis added)

Veblen’s inimitable prose may be a bit irksome to read, but reference to the italicized bits above should be enough to understand the argument. ‘Custom and prestige,’ and the ‘fabrication of popular conviction’ suggest that businesses are competing through persuasion rather than production of something of value. The second paragraph, then, considers whether these activities are actually of value to society (or perhaps, in the terminology of orthodox economics, whether or not they’re ‘welfare enhancing’). For the most part, they are decidedly not. They may create a pecuniary (that is, money) value for the business—the perception of C’ is improved and M’ increases as a result—but, to society in general they amount to little more than a needless shifting of buying habits and consumption patterns. As Professor Sturgeon notes, there’s more than one way to make money.

We should pause to consider the usefulness of this model. Separating money from commodities in the monetary production process has allowed us to consider different business activities as essentially different things. The abstract firm in standard orthodox theory might lead us to treat anything that makes a business more money as part of the production process (C…P…C’), suggesting that advertising was just another commodity in the production process improving the value of the product to be sold. By implication, then, the advertising added value to society. Yet, taking a heterodox position here and treating production and advertising as two different activities has allowed room for the argument that, in fact, the advertising was generally wasteful.

Distinguishing Arrow 1 from Arrow 2: The Pharmaceutical Industry

A contemporary example should indicate the importance of distinguishing between arrows 1 and 2. The price of pharmaceutical drugs continues to be a controversial topic in the United States, and it’s no surprise why: according to the OECD, pharmaceutical spending has risen from an average of $172 per person (or 0.86% of GDP) in 1987 to $1,310 per person (or 2.08% of GDP) in 2020. Moreover, a 2016 Reuters article found that the prices of 4 of the top 10 most widely used drugs more than doubled in just the previous 5 years.A number of factors are important to explaining these rapid price increases, including an aging population in the U.S. and an exceedingly complex distribution and insurance system for pharmaceuticals. But, let’s focus on the common explanation given by the producers themselves: high prices are necessary to recover the high costs of research and development (much of which leads to dead-end investments that don’t produce effective drugs that can be brought to market) and the clinical trials necessary for regulatory approval. Clearly, this reasoning is in line with the general framework of heterodox economic theory. Pharmaceutical companies are engaging in long-run planning, including significant investments into better products (that is, investments into P in Figure 1), and prices are a reflection of those investments.

But what’s more, our monetary production model can help us find a fuller explanation of the nature and extent of those investments. Consider estimates from Gagnon and Lexchin (2008) on promotional expenditures by the industry. The authors found that, for 2004, the industry devoted about 24% of its sales revenue to promotion, versus about 13% to research and development. Looking specifically to promotion directed at physicians, the authors estimate that approximately $61,000 was spent per physician in the U.S. To be sure, there are other estimates lower than those made by Gagnon and Lexchin. Just the same, it is clear that pharmaceutical enterprises are investing heavily not only in developing new drugs, but in promoting their use as well.

Moreover, the pharmaceutical industry provides us with a somewhat unique opportunity to clearly distinguish investments in C’ (arrow 2 in Figure 1) from investments in P (arrow 1). Because these drugs are systematically evaluated for their effectiveness in treating specific illnesses, data exist to indicate how well supposedly-arrow 1 investments are improving the product. On this matter, Gagnon (2013) finds that fewer and fewer new molecular entities (truly new drugs, without precedent in drugs already in use) are being developed, and only a small minority of new drugs represent substantial therapeutic advances over existing treatments. The proliferation of ‘me-too’ drugs, which are new products to be marketed if not actually better treatments for illnesses, suggests that the business model in this industry is focused less on improvements in P and more on inflating C’. That is, arrow 2 appears to dominate, with arrow 1 a secondary concern, in the business models of the pharmaceutical companies.

Finally, there is arrow 3, a direct line from an initial sum of money to a greater amount of money, bypassing all the troublesome in-between steps of producing and selling a good or service. This sort of business model takes many forms and is becoming increasingly popular in the capitalism of today. The traditional exemplar is the financial firm—or, say, the stock broker—which has no direct ties to actually producing something, but rather only to trading in the ownership rights of those producers.

The full role and consequences of financial firms and markets cannot be covered here. What’s of interest presently is business activity that can turn a profit without being concerned with producing something for sale, or even simply with persuading people to buy a product. You may have heard about the causes of the Great Recession of 2008-09 being chiefly linked to business models in finance, insurance, and real estate (the so-called FIRE sector). The problem, many believe, is in the opacity and complexity of a system in which mortgage contracts representing an agreement to pay for a house over time were packaged together into derivative contracts to be sold to investors, then resold, repackaged, and so on. Indeed to make a system even more complex, many financial firms were making side bets that the contracts they themselves were selling would in fact not pay out. Many articles, books, and documentaries have been produced retelling that story, and The Big Short is an effective and fairly accurate dramatization of some of those events. For now, it is enough to say that the businesses engaged in those activities were largely concerned with turning money into more money by persuading others that these contracts built on contracts (built on contracts…) were worth more than they were. These were arrow 3 business activities, having little to do with the actual business of housing people.

A century earlier, Veblen had described similar practices in the stock markets, where the goal is to,

induce a discrepancy between the putative and the actual earning-capacity, by expedients well known and approved for the purpose. Partial information, as well as misinformation, sagaciously given out at a critical juncture, will go far toward producing a favorable temporary discrepancy of this kind. (Veblen, 1904, p. 156)

It was, in 2008-2009, precisely this type of behavior which ultimately caused the deepest recession since the Great Depression (which, incidentally, had also been caused in part by this type of behavior). As a result, many of the largest banks and other financial institutions in the U.S. and abroad have been made to pay fines in the 10’s of billions of dollars. Whether these fines will be enough to make this business model unattractive in the future is debatable—but it seems unlikely.

References

Gagnon, M. A. and J. Lexchin. (2008) “The Cost of Pushing Pills: A New Estimate of Pharmaceutical Promotion Expenditures in the United States,” PLoSMedicine, 5(1), 29-33.

Gagnon, M. A. (2013) Corruption of pharmaceutical markets: Addressing the misalignment of financial incentives and public health. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 41(3), 571-580.

Humer, Caroline. (2016) “Exclusive: Makers took big price increases on widely used U.S. drugs.” Reuters. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-healthcare-drugpricing-idUSKCN0X10TH.

OECD Data. “Pharmaceutical Spending.” Available at https://data.oecd.org/healthres/pharmaceutical-spending.htm.

Veblen, Thorstein. (1904) The Theory of Business Enterprise.

Glossary

- business model

- a particular way of organizing a business including strategies for making money in a market (or several markets)

- monetary production

- the process of turning money into commodity inputs and ultimately selling commodity outputs for money

a particular way of organizing a business including strategies for making money in a market (or several markets)

the process of turning money into commodity inputs and ultimately selling commodity outputs for money

the organization of people who participate in the group decision-making that directs the business enterprise through time