33.4 – Stabilizing Unstable Markets

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Situate businesses and their business models within their market governance structures

- Define infrastructure, corporate governance, and market governance

The previous sections of this chapter dealt mainly with the nature of the modern business enterprise as an individual organization. But, of course, no business is created in a vacuum, and no business can operate in complete isolation. This section will look at the economic, social, and political nature of markets to better understand how real businesses fit into a heterodox understanding of the economy.

Any business model—including those discussed above and beyond—is a plan for how to successfully operate a business within one or more markets. A good business plan will have to consider, among other things, the competition, the potential customer base, rules and regulations, and the necessary infrastructure to produce and distribute the product, whatever it may be. Established businesses will have worked out their business models over time, will have built (or had built for them) the necessary infrastructure (for instance, roads or communications protocols), and will typically have helped define the rules and regulations that dictate which individual and competitive activities are permissible and which are not. This is to say that markets themselves are defined by (and the way business enterprises behave in these markets is guided by) their infrastructure and their corporate and market governance structures.

Definitions

Infrastructure: the common structures, facilities, and systems necessary for organizations to operate. These may include physical infrastructure like highways, bridges, electrical grids, and sewage systems; as well as systems like the complex networks of computers tied together through communications lines and protocols we know as the internet.

Corporate governance: the rules and practices defining how and by whom a business is directed as well as how members of the business will interact with each other and those outside of the business. These are both formal rules like accounting practices or the corporate hierarchy of who reports to whom, as well as informal norms, traditions, and relationships.

Market governance: the rules and practices defining how business enterprises will behave in a market, including especially how they will interact with their competitors. These may include formal agreements—for instance, a consent decree by which a business agrees not to engage in an activity the government considers anticompetitive, or a joint venture operation between two energy companies to explore a potential source of crude oil. Probably more important, though, are the various informal arrangements by which certain types of competition and cooperation between businesses are allowed while others are not.

A side note: these shared rules and infrastructure are not fixed in time—they evolve, whether by unintended consequence or intentional change. Moreover, they are socially constructed, which means there is a political element to all of them. Although we’re focusing for now on the private, business side of the matter, it should be remembered that there is almost always a government role in the development, regulation, and sometimes prohibition of these structures.

Finally, a fourth component, property rights, is worth adding. Property rights are legal norms defining who can own what, what can be done with that property, and therefore how businesses can generate earnings and who has claims on those earnings. While property is often considered simply a natural right, the actual content of property rights is a complex, perpetually evolving, and highly contested subject.

These attributes of the organization of businesses and the markets in which they operate are all geared toward essentially the same thing: stability. As an earlier section explained, most parts of the modern economy involve sophisticated and usually large-scale technologies. For this and other reasons long term planning is necessary for production to go forward, and long term planning requires predictable outcomes. Hence, markets and businesses must be organized to promote stability. of special note, as a previous section explains, businesses require predictability in prices.

Now consider the orthodox models of previous chapters. In each of these, some, perhaps natural, equilibration process is used—that is, a process by which firm’s, consumers, and ultimately markets move toward an equilibrium, toward stability. The utility maximizing consumer seeks an optimal combination of consumers goods, the profit maximizing firm seeks an optimal level of production, and the market, through competition and price bidding, moves toward the equilibrium price and output.

Many heterodox economists reject each of these models, in part because of the unrealistic mechanisms by which equilibrium is reached. For instance, as chapter “Costing and Pricing in Going Concerns” demonstrates, few markets in the modern U.S. economy are characterized by the sort of price adjustments that the standard market model relies on to reach a stable equilibrium. Moreover, considerable evidence suggests that competition—especially price competition—actually promotes instability. And it is for this reason that the concept of market governance is so important. Without a workable set of norms concerning acceptable and unacceptable forms of competition and cooperation, most markets would never be stable, let alone capable of reaching an equilibrium. Instead, price competition and chicanery would wreak havoc on businesses and consumers alike.

Finance, governance, and (in)stability

The heterodox perspective on markets, emphasizing the social relationships and norms that comprise governance, looks to understand markets as changing structures of power and norms. There is no ‘natural’ process of finding stability or equilibrium through the voluntary interaction of individuals. Indeed, voluntary interaction itself is considered less relevant than the power relationships that are typical when people interact with large corporations.

In this section, you’ve learned that the market and corporate governance norms that make up the actual economic system have been constructed chiefly with the goal of stability in mind—more specifically, stability for the dominant businesses who are principally responsible for creating these norms. But—and it would be impossible to over-emphasize this point—things always change.

Take for instance the role of finance in American capitalism. A century ago, big business relied in part on banks and the stock markets to finance their investments, but bankers and stock brokers didn’t usually run the businesses themselves. Indeed, in the early 20th century many of the top executives of these corporations came from a manufacturing or engineering background. There was no such thing as a Chief Financial Officer (CFO), that position being given the less prestigious title of treasurer.

Fast forward to the 1990s. By this time it had become common for corporations to declare that their only objective was to ‘maximize shareholder value’, which usually meant boosting their stock price as high as possible. CFOs had become much more prominent within these organizations, and it was common for the CEO to have a background not in engineering or even marketing, but rather in finance. Referring back to Figure 1 in the previous section, we could say that the dominant corporate governance norms had shifted from arrows 1 and 2 to arrow 3, making money from money with little concern for producing or even selling an actual product.

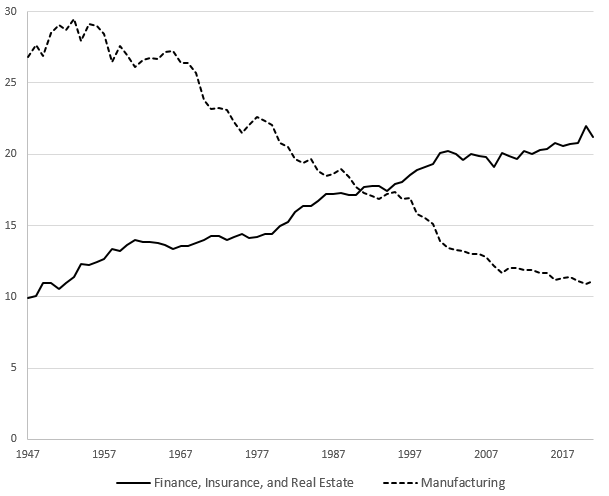

This change in the overall makeup of the American economy is evident in figure 1 below. While value added in manufacturing industries has declined from just under 30% of GDP in the 1950s to just over 10% in recent years, valued added in the FIRE sector (that is, finance, insurance, and real estate) has more than doubled, from 10% to over 20% of GDP.

Did this change promote stability? Well, it depends on whose stability. For many in the FIRE sector, vast fortunes have been amassed (and more than one presidential campaign financed) through expanding financial and real estate trade. The largest banks in the U.S. are now considered ‘too big to fail’, meaning the federal government will not allow them to go under no matter how poorly they manage their investments.

For many others, however, the increasing use of debt financing for cars, education, and any number of other basic goods and services has created greater instability. Many households today find themselves only one cut in working hours, one unexpected bill, or one illness away from being unable to pay their bills.

This financialization of the American economy shines a light on two important points worth remembering about the governance approach of heterodox economics. First, the norms, rules, and so on that businesses develop over time change, and even though the goal is generally to create stability, that isn’t necessarily going to be the outcome. Second, this perspective emphasizes unequal power structures, and this applies to the issue of stability as well. That is, a set of rules that promotes stability for one kind of organization—for instance, hedge funds—may very well be destabilizing for others—for instance, workers, students, or state governments.

Glossary

- infrastructure

- the common structures, facilities, and systems necessary for organizations to operate

- corporate governance

- the rules and practices defining how and by whom a business is directed as well as how members of the business will interact with each other and those outside of the business

- market governance

- the rules and practices defining how business enterprises will behave in a market, including especially how they will interact with their competitors

- property rights

- legal norms defining who can own what, what can be done with that property, and therefore how businesses can generate earnings and who has claims on those earnings

a particular way of organizing a business including strategies for making money in a market (or several markets)

the common structures, facilities, and systems necessary for organizations to operate

the rules and practices defining how and by whom a business is directed as well as how members of the business will interact with each other and those outside of the business

the rules and practices defining how business enterprises will behave in a market, including especially how they will interact with their competitors

legal norms defining who can own what, what can be done with that property, and therefore how businesses can generate earnings and who has claims on those earnings