76 Dissipation by Drag Forces

The Drag Force

When cycling, driving, running, or any other time that an object moves through air it must push air out of the way. Newton’s 3rd Law makes it clear that the air will put a force back on the object, and we call that force air resistance. Air resistance is a specific case of the drag force, which occurs any time an object moves through any fluid (liquid or gas). Drag force can be broken into two types: form drag and skin drag. Form drag is caused by the resistance of fluids to being pushed out of the way by an object in motion through the fluid. Skin drag is essentially a kinetic frictional force caused by the sliding of the fluid along the surface of the object. The drag force pushes in the opposite direction of the object motion, so it must do negative work on the object, meaning that it transfers kinetic energy out of the object. Conversely, the object does positive work on the fluid molecules, which increases their kinetic energy. Continued collisions between fluid molecules spreads that extra kinetic energy throughout the fluid. Remembering that kinetic energy of microscopic particles is how we define thermal energy, we can say that kinetic energy of the moving object was dissipated into the fluid environment as thermal energy. In order to maintain a constant speed, kinetic energy must be added to the system from another source a the same rate as the drag force dissipates kinetic energy. The dissipation rate depends on the object speed and and the size of the drag force, which itself depends on the speed and several other factors. This chapter will examine how those factors affect efficiency.

The drag force depends the density of the fluid (ρ), the maximum cross-sectional area of the object(![]() ), and the drag coefficient (

), and the drag coefficient (![]() ), which accounts for the shape of the object. Objects with a low drag coefficient are often referred to as having an aerodynamic or streamlined shape. The drag force always depends in some way on the on the relative speed (

), which accounts for the shape of the object. Objects with a low drag coefficient are often referred to as having an aerodynamic or streamlined shape. The drag force always depends in some way on the on the relative speed (![]() ) between the object and the fluid. If the object is not very small and has a density that is not much smaller than the fluid, and the fluid is not very viscous then the drag force actually depends on

) between the object and the fluid. If the object is not very small and has a density that is not much smaller than the fluid, and the fluid is not very viscous then the drag force actually depends on ![]() and can be calculated with the formula:

and can be calculated with the formula:

(1) ![]()

Air resistance on the body, bicycles, and cars generally follows the formula above. The image below illustrates how the shape of an objects affects the drag coefficient. The table below the image provides drag coefficient values for a variety of objects.

| Object | Drag Coefficient (C) |

| Airfoil | 0.05 |

| Toyota Camry | 0.28 |

| Ford Focus | 0.32 |

| Honda Civic | 0.36 |

| Ferrari Testarossa | 0.37 |

| Dodge Ram pickup | 0.43 |

| Sphere | 0.45 |

| Hummer H2 SUV | 0.64 |

| Skydiver (feet first) | 0.70 |

| Bicycle | 0.90 |

| Skydiver (horizontal) | 1.0 |

| Circular flat plate | 1.12 |

Reinforcement Exercises

Everyday Examples: Air Resistance and Walking Efficiency

We would like to determine if air resistance plays an important role in Walking efficiency. According to the chart in the previous unit titled Energy and Oxygen Consumption Rates for an average 76 kg male, walking at 5 km/hr requires 280 Watts power. Converted to units of m/s that speed is 0.28 m/s. We will use that speed to find the rate at which negative work done by air resistance dissipates energy from the body and compare that to the overall 280 Watts.

We start with the work equation:

(2) ![]()

The drag force acts opposite to the body motion of the body so ![]() .

.

(3) ![]()

Dividing both sides by time allows us to calculate the power, the rate at which work is done.

(4) ![]()

On the right side is distance divided by time, which is just the speed, ![]() .

.

(5) ![]()

Entering the drag force equation for the force variable:

(6) ![]()

Combining all the speed variables gives a ![]() .

.

(7) ![]()

Drag coefficient of the body depends on orientation and is typically between 0.4-1.3. A reasonable approximation would be to use the value for a horizontal body position while falling, which is ![]() as seen in the chart above. To approximate the cross-sectional area we can use the author’s average width of 0.3 m and height of 1.5 m for an area of

as seen in the chart above. To approximate the cross-sectional area we can use the author’s average width of 0.3 m and height of 1.5 m for an area of ![]() . The density of air at sea level is 1.21 kg/m3. Entering these values:

. The density of air at sea level is 1.21 kg/m3. Entering these values:

(8) ![]()

That dissipation power is very small compared to the 280 Watts of power used for walking. It looks air resistance does not play a significant role in walking efficiency. We see that the rate of energy dissipation depends on the speed cubed, so speed matters a lot in determining energy dissipation by air resistance. Walking speed is just to slow for air resistance to matter much. Next we will calculate the effects of air resistance when cycling and skydiving. We will see that air resistance does become important at cycling speeds and falling speeds.

Everyday Examples: Air Resistance When Driving

In the previous example we found an equation for the dissipation power and we can use that same equation here, by entering new values for the drag coefficients and speeds. That is the beauty of working symbolically!

Starting with the dissipation power from the previous example:

(9) ![]()

According to the chart above, the drag coefficient of a Dodge Ram Pickup is 0.43. The height and width of such a truck are each about 2 m, for a cross section of 4 m2. A highway driving speeds of 65 mph converts to 29 m/s and the density of of air at sea level is 1.21 kg/m3. Entering these values:

(10) ![]()

Dividing our result by 746 W/hp, we see that balancing dissipation by air resistance requires about 34 hp, or roughly 10% of the maximum hp for such a truck. If we instead multiply our result by 3600 s/hr we find that balancing air resistance requires roughly ![]() of energy each hour. At 65 mph this same energy is required every 65 miles traveled. The approximate fuel efficiency of such a truck is 15 mpg, so dividing 65 miles by 15 mpg, we see that for every 4.33 gallons of gas burned,

of energy each hour. At 65 mph this same energy is required every 65 miles traveled. The approximate fuel efficiency of such a truck is 15 mpg, so dividing 65 miles by 15 mpg, we see that for every 4.33 gallons of gas burned, ![]() of energy was used to move air out of the way. A gallon of gasoline contains about

of energy was used to move air out of the way. A gallon of gasoline contains about ![]() of usable chemical potential energy, so 4.33 gallons contains

of usable chemical potential energy, so 4.33 gallons contains ![]() . Dividing the energy used to move air out of the way by the total energy used we get:

. Dividing the energy used to move air out of the way by the total energy used we get: ![]() . In other words, the engine is only about 16% mechanically efficient because only 16% of the energy used actually went to doing some kind of work on the environment, the rest went to thermal energy. In the following chapters we will see why the efficiency of internal combustion engines is so low.

. In other words, the engine is only about 16% mechanically efficient because only 16% of the energy used actually went to doing some kind of work on the environment, the rest went to thermal energy. In the following chapters we will see why the efficiency of internal combustion engines is so low.

Everyday Examples: Terminal Speed of the Human Body

After jumping, a skydiver begins gaining speed which increases the air resistance they experience. Eventually they will move fast enough that the air resistance is equal in size to their weight, but in opposite direction so they have no net force. With no net work, their kinetic energy cannot change so the will maintain a constant speed (work energy theorem). In other words, at that point the rate at which air resistance does negative work on the body has caught up with the rate at which gravity is doing positive work. Just as quickly as gravitational potential energy is being converted to kinetic energy, that energy is dissipated to thermal energy in the environment.

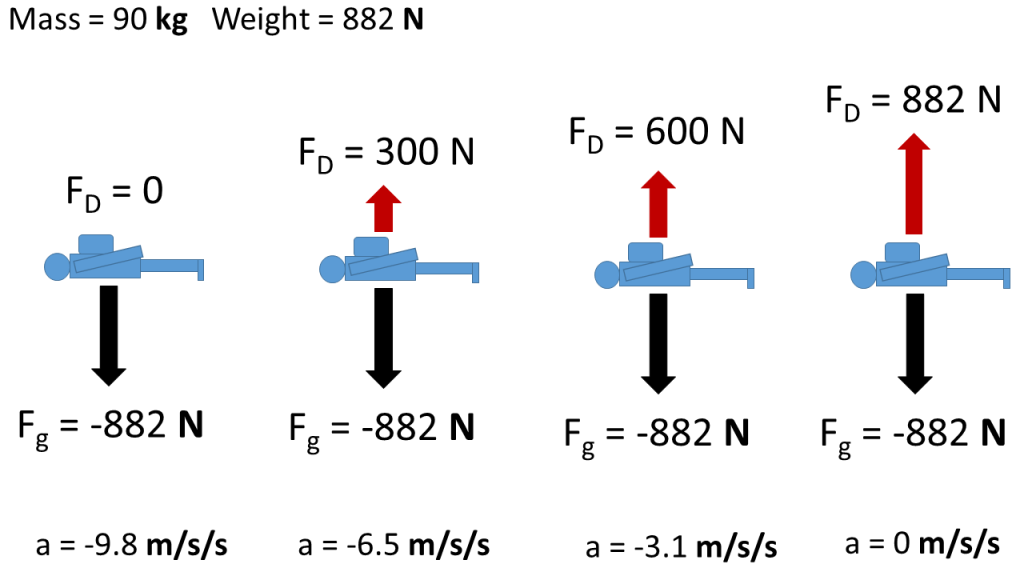

Alternatively, we can think in terms of Newton’s First in which case we know their speed cannot change anymore because with no net force they must have no further acceleration. Either way we analyze it, the falling body will reach a maximum speed, which we call the terminal speed. This processes is illustrated by free body diagrams for a skydiver with 90 kg mass in the following image, which shows the acceleration values calculated using Newton’s Second Law:

With the understanding that terminal speed is reached when the drag force and weight are equal we can derive a model for the terminal speed and examine how it depends on various factors. We start by equating the weight and drag forces.

![]()

Then we insert the formulas for air resistance and for weight of an object near Earth’s surface. We designate the speed in the resulting equation ![]() because these two forces are only equal at terminal speed.

because these two forces are only equal at terminal speed.

![]()

We then need to solve the above equation for the terminal speed.

(11) ![]()

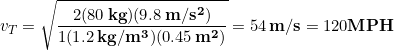

Let’s estimate the terminal speed of the human body. We start with the previous equation:

![]()

We need to know the mass, drag coefficient, density of air, and cross-sectional area of the human body. Let’s use the authors 80 kg mass and the density of air near the Earth’s surface at standard pressure and temperature, ![]() . Drag coefficient and cross sectional area depend on body orientation, so let’s assume a standard skydiving posture: flat, horizontal, with arms and legs spread. In this case the drag coefficient will likely be 0.4-1.3. A reasonable value would be

. Drag coefficient and cross sectional area depend on body orientation, so let’s assume a standard skydiving posture: flat, horizontal, with arms and legs spread. In this case the drag coefficient will likely be 0.4-1.3. A reasonable value would be ![]() [4]. To approximate the cross-sectional area we can use the authors average width of 0.3 m and height of 1.5 m for an area of

[4]. To approximate the cross-sectional area we can use the authors average width of 0.3 m and height of 1.5 m for an area of ![]()

Inserting these values into our terminal speed equation we have:

First-time skydivers are typically attached to an instructor (tandem skydiving). During a tandem skydive the bodies are stacked, so the shape and cross-sectional area of the object don’t change much, but the mass does. As a consequence, the terminal speed for tandem diving would be high enough to noticeably reduce the fall time and possibly be dangerous. Increasing the air resistance to account for the extra mass is accomplished by deploying a small drag-chute that trails behind the skydivers, as seen in the photo below.

Reinforcement Exercises

- "Drag of a Sphere" by Glenn Research Center Learning Technologies Project, NASA, via GIPHY is in the Public Domain, CC0 ↵

- Drag of Car By Eshaan 1992 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons ↵

- OpenStax, College Physics. OpenStax CNX. Jan 17, 2019 http://cnx.org/contents/031da8d3-b525-429c-80cf-6c8ed997733a@14.5 ↵

- "Drag Coefficient" by Engineering Toolbox ↵

- By Jochen Schweizer GmbH [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons ↵

a force acting opposite to the relative motion of any object moving with respect to a surrounding fluid

the force of gravity on on object, typically in reference to the force of gravity caused by Earth or another celestial body

the total amount of remaining unbalanced force on an object

a graphical illustration used to visualize the forces applied to an object

a measurement of the amount of matter in an object made by determining its resistance to changes in motion (inertial mass) or the force of gravity applied to it by another known mass from a known distance (gravitational mass). The gravitational mass and an inertial mass appear equal.

relation between the amount of a material and the space it takes up, calculated as mass divided by volume.