38 Friction in Joints

Synovial Joint Friction

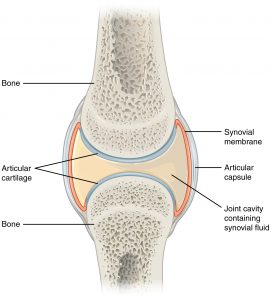

Static and kinetic friction are both present in joints. Static friction must be overcome, by either muscle tension or gravity, in order to move. Once moving, kinetic friction acts to oppose motion, cause wear on joint surfaces, generate thermal energy, and make the body less efficient. (We will examine the efficiency of the body later in this textbook.) The body uses various methods to decrease friction in joints, including synovial fluid, which serves as a lubricant to decrease the friction coefficient between bone surfaces in synovial joints (the majority of joints in the body). Bone surfaces in synovial joints are also covered with a layer of articular cartilage which acts with the synovial fluid to reduce friction and provides something other than the bone surface to wear away over time[1]. We ignored friction when analyzing our forearm as a lever because the frictional forces are relatively small and because they acted inside the joint, very close to the pivot point so they caused negligible torque.

Reinforcement Exercises

The cartilage-on-cartilage kinetic friction coefficient within synovial joints has been measured to be as low as 0.002[2].

- OpenStax, Anatomy & Physiology. OpenStax CNX. Jun 25, 2018 http://cnx.org/contents/14fb4ad7-39a1-4eee-ab6e-3ef2482e3e22@10.1. ↵

- Farshid Guilak, ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM Vol. 52, No. 6, June 2005, pp 1632–1633 DOI 10.1002/art.21051 ↵

a force that resists the tenancy of surfaces to slide across one another due to a force(s) being applied to one or both of the surfaces

the force that is provided by an object in response to being pulled tight by forces acting from opposite ends, typically in reference to a rope, cable or wire

attraction between two objects due to their mass as described by Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation

a force that resists the sliding motion between two surfaces