13 Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are macromolecules with which most consumers are somewhat familiar. To lose weight, some individuals adhere to “low-carb” diets. Athletes, in contrast, often “carb-load” before important competitions to ensure that they have sufficient energy to compete at a high level. Carbohydrates are, in fact, an essential part of our diet; grains, fruits, and vegetables are all natural sources of carbohydrates. Carbohydrates provide energy to the body, particularly through glucose, a simple sugar. Carbohydrates also have other important functions in humans, animals, and plants.

Carbohydrates can be represented by the stoichiometric formula (CH2O)n, where n is the number of carbons in the molecule. In other words, the ratio of carbon to hydrogen to oxygen is 1:2:1 in carbohydrate molecules. This formula also explains the origin of the term “carbohydrate”: the components are carbon (“carbo”) and the components of water (hence, “hydrate”). Carbohydrates are classified into three subtypes: monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides.

Monosaccharides

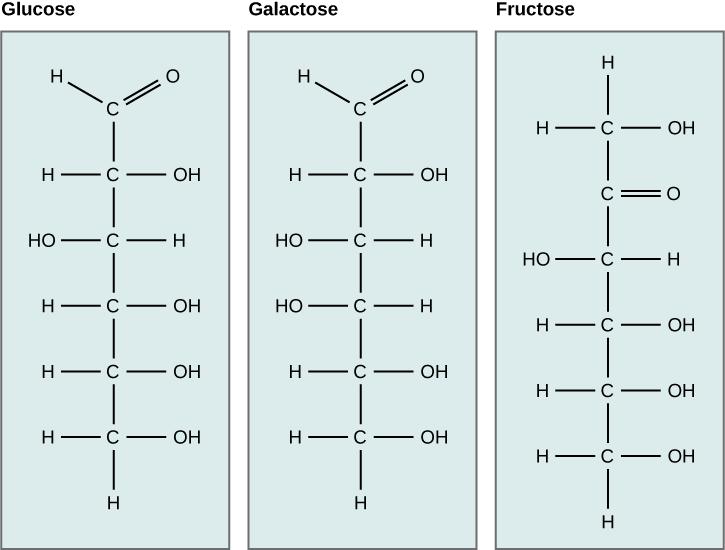

Monosaccharides (mono- = “one”; sacchar- = “sweet”) are simple sugars, the most common of which is glucose. In monosaccharides, the number of carbons usually ranges from three to seven. Most monosaccharide names end with the suffix -ose.

The chemical formula for glucose is C6H12O6. In humans, glucose is an important source of energy. During cellular respiration, energy is released from glucose, and that energy is used to help make adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Plants synthesize glucose using carbon dioxide and water, and glucose in turn is used for energy requirements for the plant. Excess glucose is often stored as starch that is catabolized (the breakdown of larger molecules by cells) by humans and other animals that feed on plants.

Galactose (part of lactose, or milk sugar) and fructose (found in sucrose, in fruit) are other common monosaccharides. Although glucose, galactose, and fructose all have the same chemical formula (C6H12O6), they differ structurally and chemically (and are known as isomers) because of the different arrangement of functional groups around the asymmetric carbon; all of these monosaccharides have more than one asymmetric carbon. Within one monosaccharide, all of the atoms are connected to each other with strong covalent bonds.

Disaccharides

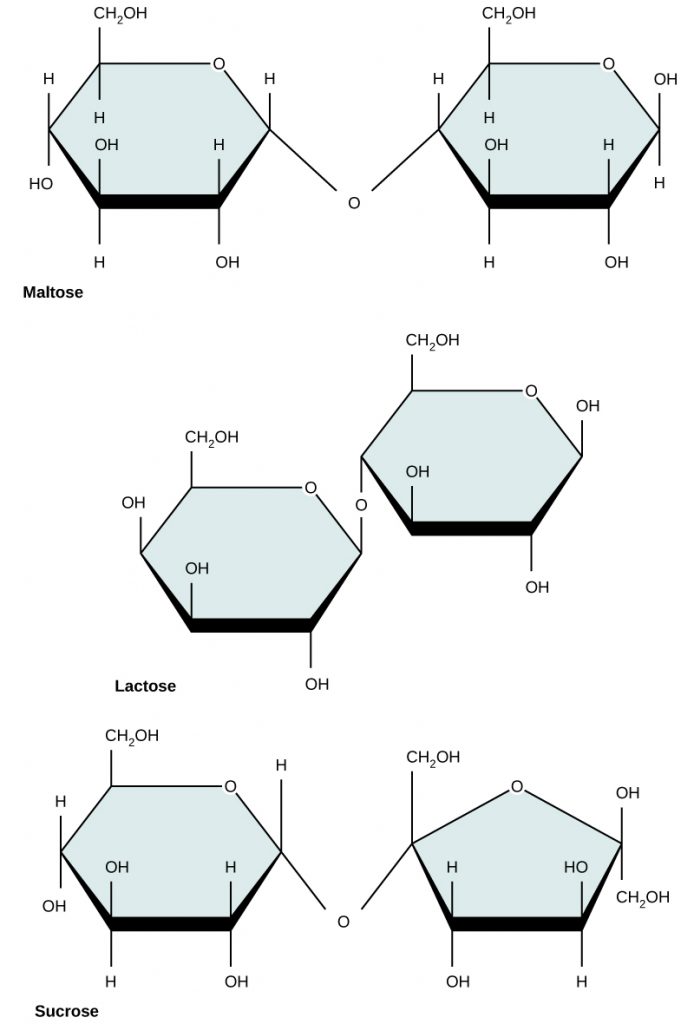

Disaccharides (di- = “two”) form when two monosaccharides undergo a dehydration reaction (also known as a condensation reaction or dehydration synthesis). During this process, the hydroxyl (OH) group of one monosaccharide combines with the hydrogen of another monosaccharide, releasing a molecule of water and forming a covalent bond which joins the two monosaccharides together.

Common disaccharides include lactose, maltose, and sucrose (Figure 3). Lactose is a disaccharide consisting of the monomers glucose and galactose. It is formed by a dehydration reaction between the glucose and the galactose molecules, which removes a water molecule and forms a covalent bond. connected by a covalent bond. It is found naturally in milk. Maltose, or malt sugar, is a disaccharide composed of two glucose molecules connected by a covalent bond. The most common disaccharide is sucrose, or table sugar, which is composed of the monomers glucose and fructose, also connected by a covalent bond.

Polysaccharides

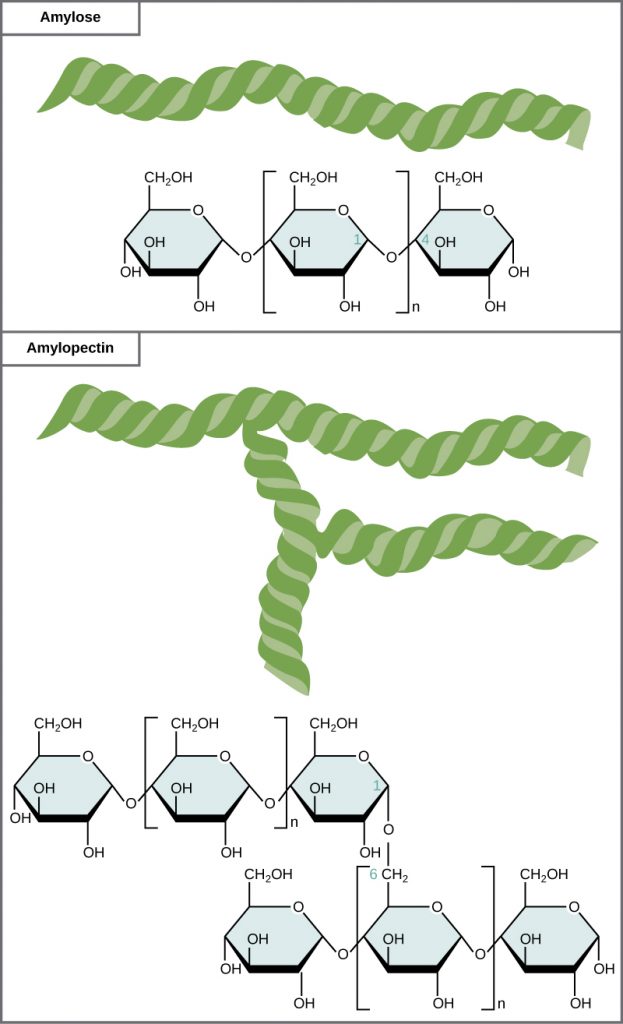

A long chain of monosaccharides linked by glycosidic bonds is known as a polysaccharide (poly- = “many”). The chain may be branched or unbranched, and it may contain different types of monosaccharides. All of the monosaccharides are connected together by covalent bonds. The molecular weight may be 100,000 daltons or more depending on the number of monomers joined. Starch, glycogen, cellulose, and chitin are primary examples of polysaccharides.

Starch is the stored form of sugars in plants and is made up of a mixture of amylose and amylopectin (both polymers of glucose). Basically, starch is a long chain of glucose monomers. Plants are able to synthesize glucose, and the excess glucose, beyond the plant’s immediate energy needs, is stored as starch in different plant parts, including roots and seeds. The starch in the seeds provides food for the embryo as it germinates and can also act as a source of food for humans and animals. The starch that is consumed by humans is broken down by enzymes, such as salivary amylases, into smaller molecules, such as maltose and glucose. The cells can then absorb the glucose.

Glycogen is the storage form of glucose in humans and other vertebrates and is made up of monomers of glucose. Glycogen is the animal equivalent of starch and is a highly branched molecule usually stored in liver and muscle cells. Whenever blood glucose levels decrease, glycogen is broken down to release glucose in a process known as glycogenolysis.

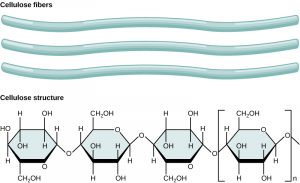

Cellulose is the most abundant natural biopolymer. The cell wall of plants is mostly made of cellulose; this provides structural support to the cell. Wood and paper are mostly cellulosic in nature. Cellulose is made up of glucose monomers (Figure 5).

Carbohydrates serve various functions in different animals. Arthropods (insects, crustaceans, and others) have an outer skeleton, called the exoskeleton, which protects their internal body parts (as seen in the bee in Figure 6). This exoskeleton is made of the biological macromolecule chitin, which is a polysaccharide-containing nitrogen. It is made of repeating units of N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamine, a modified sugar. Chitin is also a major component of fungal cell walls; fungi are neither animals nor plants and form a kingdom of their own in the domain Eukarya.

How does carbohydrate structure relate to function?

Energy can be stored within the bonds of a molecule. Bonds connecting two carbon atoms or connecting a carbon atom to a hydrogen atom are high energy bonds. Breaking these bonds releases energy. This is why our cells can get energy from a molecule of glucose (C6H12O6).

Polysaccharides form long, fibrous chains which are able to build strong structures such as cell walls.

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 27, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.10:QhGQhr4x@6/Biological-Molecules