11 Buffers, pH, Acids, and Bases

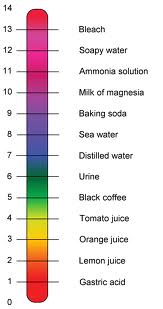

The pH of a solution is a measure of its acidity or alkalinity. You may have used litmus paper or purple cabbage juice, which can both be used as a pH indicator – they change different colors in the presence of an acid or a base. You might have used a pH indicator to make sure the water in an outdoor swimming pool is properly treated. In both cases, this pH test measures the amount of hydrogen ions (H+) that exists in a given solution. High concentrations of hydrogen ions yield a low pH, whereas low levels of hydrogen ions result in a high pH. The overall concentration of hydrogen ions is inversely related to its pH and can be measured on the pH scale (Figure 1). Therefore, the more hydrogen ions present, the lower the pH; conversely, the fewer hydrogen ions, the higher the pH.

The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14. A change of one unit on the pH scale represents a change in the concentration of hydrogen ions by a factor of 10, a change in two units represents a change in the concentration of hydrogen ions by a factor of 100. Thus, small changes in pH represent large changes in the concentrations of hydrogen ions. Pure water is neutral. It is neither acidic nor basic, and has a pH of 7.0. Anything below 7.0 (ranging from 0.0 to 6.9) is acidic, and anything above 7.0 (from 7.1 to 14.0) is alkaline (basic). The blood in your veins is slightly alkaline (pH = 7.4). The environment in your stomach is highly acidic (pH = 1 to 2). Orange juice is mildly acidic (pH = approximately 3.5), whereas baking soda is basic (pH = 9.0).

Acids are substances that provide hydrogen ions (H+) and lower pH, whereas bases provide hydroxide ions (OH–) and raise pH. The stronger the acid, the more readily it donates H+. For example, hydrochloric acid and lemon juice are very acidic and readily give up H+when added to water. Conversely, bases are those substances that readily donate OH–. The OH– ions combine with H+to produce water, which raises a substance’s pH. Sodium hydroxide and many household cleaners are very alkaline and give up OH–rapidly when placed in water, thereby raising the pH.

Most cells in our bodies operate within a very narrow window of the pH scale, typically ranging only from 7.2 to 7.6. If the pH of the body is outside of this range, the respiratory system malfunctions, as do other organs in the body. Cells no longer function properly, and proteins will break down. Deviation outside of the pH range can induce coma or even cause death.

So how is it that we can ingest or inhale acidic or basic substances and not die? Buffers are the key. Buffers readily absorb excess H+or OH–, keeping the pH of the body carefully maintained in the aforementioned narrow range (they help maintain homeostasis). Carbon dioxide is part of a prominent buffer system in the human body; it keeps the pH within the proper range. This buffer system involves carbonic acid (H2CO3) and bicarbonate (HCO3–) anion. If too much H+enters the body, bicarbonate will combine with the H+to create carbonic acid and limit the decrease in pH. Likewise, if too much OH–is introduced into the system, carbonic acid will rapidly dissociate into bicarbonate and H+ions. The H+ions can combine with the OH–ions, limiting the increase in pH. While carbonic acid is an important product in this reaction, its presence is fleeting because the carbonic acid is released from the body as carbon dioxide gas each time we breathe. Without this buffer system, the pH in our bodies would fluctuate too much and we would fail to survive.

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Concepts of Biology. OpenStax CNX. March 22, 2017 https://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.21:t90BfSb7@4/Water