9.2 THE BIG PICTURE: Clarity and Concision

Focusing only on individual sentences or words can be a problem for writers. That’s like driving while looking only a few feet in front of you. Experienced drivers instead take in the larger scene so that they can more effectively identify and avoid potential problems. They turn left; they turn right; they speed up or slow down.

Good writing is like that, too. After you’ve put in the time and effort to understand the big picture, then most of the small details happen automatically. If you have a strong thesis and a clear sequence of main points and supporting details, then many of the sentence-level issues take care of themselves. Editing shouldn’t be difficult.

Good academic writing is a balance between being precise and being easily understood. Some students write too simply and generally. For example, they might use only slang and simple sentences. Others, however, have complicated writing that becomes difficult to understand. Both can be obstacles between you and your reader. Therefore, when you edit, it is important to consider both clarity (are you being clear?) and concision (are you saying only what needs to be said?).

The best way to achieve clarity and concision in writing is to separate the drafting process from the revising process. Remember? Good writing comes from rewriting.

Revise for clarity

What makes a complex line of thinking easy to follow?

In general, the qualities of clarity include:

- carefully defined purpose (check your thesis statement)

- well-structured sentences (check your grammar and mechanics, such as spelling, capitalization, and punctuation)

- precise word choice (use formal academic vocabulary in the right form)

Some authors offer another key point. They explain that readers believe writing is clearer when the “characters” are the grammatical subjects and the key actions are the verbs. To illustrate the principle, compare these two versions of text:

| Version A | Version B |

|

People feel nostalgic not about the internal structure of 1950s families. Rather, the beliefs about how the 1950s provided a more family-friendly economic and social environment, an easier climate in which to keep kids on the straight and narrow, and above all, a greater feeling of hope for a family’s long-term future (especially for its young) are what lead to those nostalgic feelings. |

What most people really feel nostalgic about has little to do with the internal structure of 1950s families. It is the belief that the 1950s provided a more family- friendly economic and social environment, an easier climate in which to keep kids on the straight and narrow, and above all, a greater feeling of hope for a family’s long-term future, especially for its young. |

|

Version A is difficult to read because the “character” changes suddenly from “people” to “beliefs” (which works against cohesion) and the reader has to get to the end of the sentence to learn how these beliefs fit in. |

In Version B, however, the “character” is a belief rather than a person or thing, and it keeps the character consistent and explains what that character does (creates nostalgia) to who (people at large). |

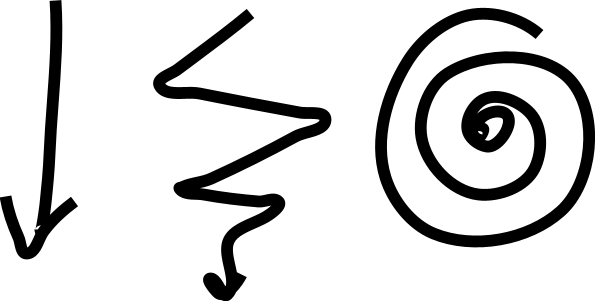

However, clarity in writing is often connected to a writer’s style. And this is something that ESOL students don’t always notice. Different cultures and languages have different patterns of organization. In other words, they tell stories or report information in different ways. Imagine if these three different lines were a map of the ideas in your paper:

There’s nothing wrong with any of these paths. However, can you guess which one is most common in English? If you guessed the straight line, you’re right. “Direct and to the point” — that’s what clear, academic writing looks like in American English.

Revise for concision

Every word and sentence should be doing some significant work for the paper as a whole. Sometimes that work is more to provide pleasure than meaning — you don’t need to eliminate every hint of description in your writing — but everything in the final version should add something unique to the paper. As with clarity, the benefits of concision are intellectual as well as stylistic: revising for concision (that means writing with as few words as possible) forces writers to make deliberate choices.

Here are three things you can do to make your writing more concise:

- Look for words and phrases that you can cut entirely. It’s common for students to write repetitive material as they figure out exactly what they want to say. Delete these bits to tighten your writing.

- Look for opportunities to replace longer phrases with shorter phrases or words. For example, “the way in which” can often be replaced by “how” and “despite the fact that” can usually be replaced by “although.” Strong, precise verbs can often replace longer phrases. Consider this example: “The goal of Alexander the Great was to create a united empire across a vast distance.” Now compare it to this: “Alexander the Great wanted to unite a vast empire.”

- Try to rearrange sentences or passages to make them shorter and livelier. Some instructors suggest changing negatives to affirmatives. Consider the negatives in this sentence: “School nurses often do not notice if a young child does not have adequate food at home.” You could more concisely and clearly write, “School nurses rarely notice if a young child lacks adequate food at home.” It says the same thing, but it is much easier to read which makes for a happier and more engaged reader.

DISCUSSION

Clarity and concision are important concepts to good writing. But what do they really mean? Read this page again. Look up the words in different dictionaries. Then put all of those materials away and write a one-sentence definition for each term in your own words.

Text adapted from: Guptill, Amy. Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence. 2022. Open SUNY Textbooks, 2016, milneopentextbooks.org/writing-in-college-from-competence-to-excellence/. Accessed 16 Jan. 2022. CC BY-NC-SA