Best Practices For Weight Management

With over 70 percent of Americans currently overweight or obese, it isn’t surprising that many individuals report engaging in weight management efforts.1 In fact, a 2019 report from a national survey on current trends in weight loss attempts and strategies found that 42 percent of adults in the United States had recently attempted to lose weight, primarily through reduced food consumption and exercise.2 In this unit we examine the best practices for weight management based on the body of evidence from many years of scientific research.

Biology Behind the Challenge of Weight Loss

We have just considered the gravity of the obesity problem in the U.S. and worldwide. How is the U.S. combating its weight problem on a national level, and have the approaches been successful? Successful weight loss is defined as individuals intentionally losing at least 10 percent of their body weight and keeping it off for at least one year.3 Results from some lifestyle intervention studies suggest that most individuals are not successful at long-term weight loss. Yet an evaluation of successful weight loss involving more than fourteen thousand participants published in the November 2011 issue of the International Journal of Obesity estimated that more than one in six Americans (17 percent) who were overweight or obese were successful at both achieving and maintaining a significant level of weight loss.4 While this estimate is more promising than other studies suggest, it still raises the question: Why is achieving long-term weight loss so difficult? Much of the explanation lies in understanding the biology of weight loss.

Weight loss has often been viewed as a simple formula: energy in versus energy out. If you consume more calories than you expend, you gain weight. If you expend more calories than you consume, you lose weight. This is the general principle of energy balance, as discussed earlier in this unit, and this principle gives foundation to the basic premise of weight management.

However, the body is more complex than a simple formula. And much like many functions within the body, weight is tightly regulated. In order to prevent perpetual weight loss or weight gain every time environmental or behavioral factors change, mechanisms within the body adjust to help normalize weight at a steady point.5 But our obesogenic environment often promotes behaviors that encourage excessive caloric intake and lower energy expenditure, leading to a higher steady weight over time. When an individual focuses on losing weight, active weight loss efforts often yield initial weight loss. But those same mechanisms that work to maintain a steady weight also kick in during periods of weight loss to help the body defend the original weight.5 The body recognizes weight loss as a threat to survival, lowering basal metabolic rate to preserve calories and protect against starvation. Additionally, as someone loses weight, there is less physical mass to the body that has to be moved from place to place throughout the day, resulting in fewer calories burned through physical movement and activity, and less metabolically active tissue using calories for fuel throughout the day.

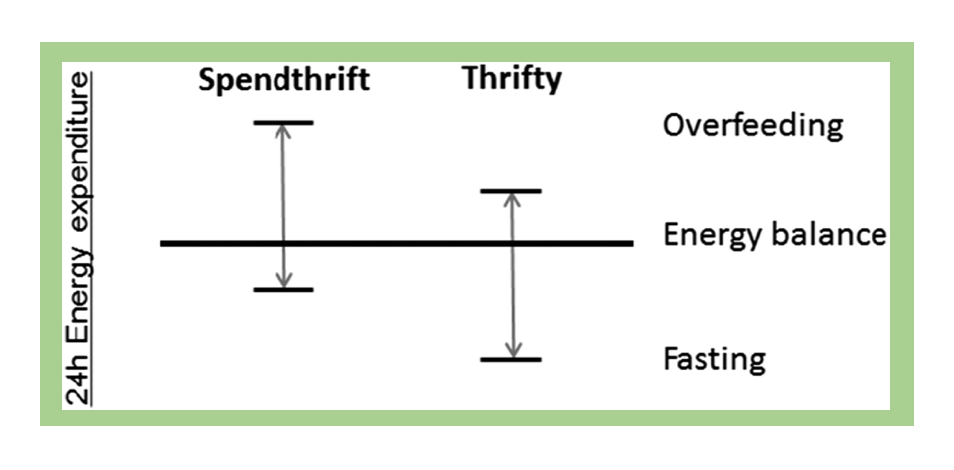

Biological differences in individual metabolism may also impact weight loss success. Researchers have found that some individuals have a “thrifty” metabolism, meaning that they have a lower metabolic rate and expend significantly fewer calories when in a fasting (or calorie-restricted) state, common in weight loss efforts. This results in a lower level of weight loss. In contrast, individuals with a “spendthrift” metabolism tend to have a higher metabolic rate in a fasting state, burning more calories and thus yielding bigger weight loss results.6 According to researcher Martin Reinhardt, M.D., “The results corroborate the idea that some people who are obese may have to work harder to lose weight due to metabolic differences.”7

Figure 7.24. Illustration of the concept of spendthrift and thrifty metabolisms, characterized by their response to overfeeding and fasting.

To add to the challenge of metabolic differences, research also suggests that changes in hormone levels due to weight loss may impact the body’s ability to maintain a lower weight. Decreases in thyroid hormones that regulate metabolism, as well as changes in hormones such as leptin and insulin that affect satiety levels, contribute to the challenge of maintaining a lower weight after initial weight loss occurs.5,8 In individuals maintaining a 10% or greater weight loss, all of these changes combine to account for an estimated decrease of 300-400 calories in energy expenditure per day beyond what is expected due to the change in body composition alone.8 These biological factors and their influence on weight are discussed further in the below video.

VIDEO: “The Quest to Understand the Biology of Weight Loss,” by HBO Docs, YouTube (May 14, 2012), 22:52 minutes.

Evidence-Based Approaches to Weight Loss

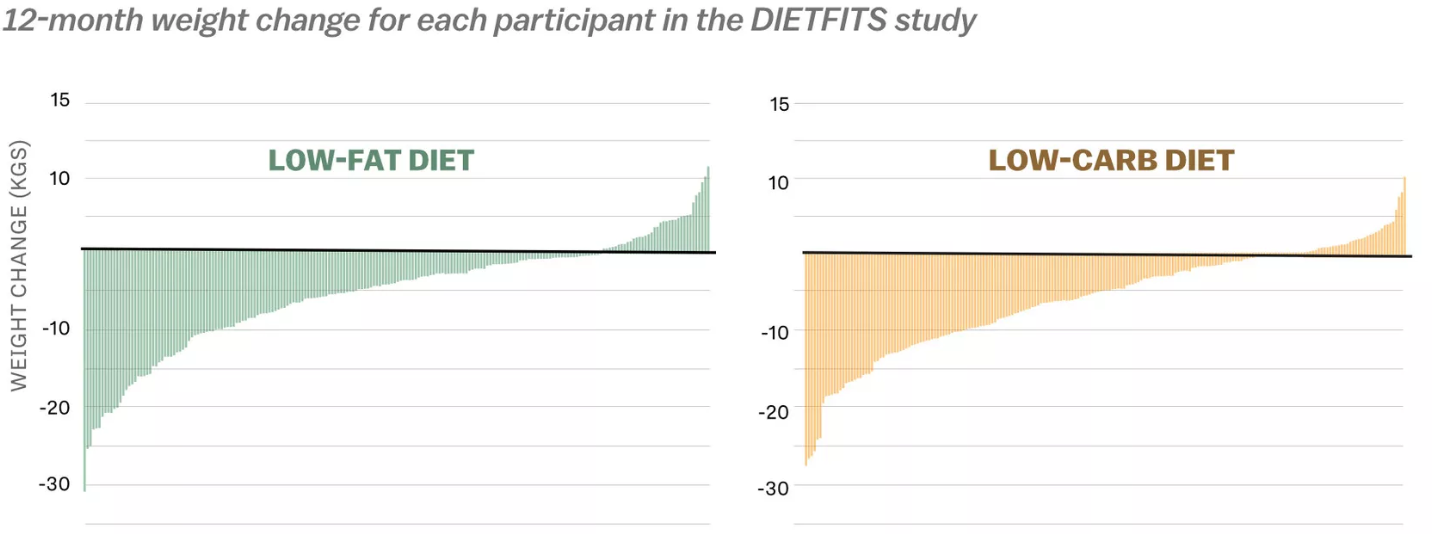

In spite of the challenges imposed by biological processes in the body, there is significant evidence to suggest that successful weight loss and maintenance is possible. There are many approaches when considering options for weight loss, and no single treatment is right for everyone. In fact, while following a lower-calorie healthy eating plan is often the first approach to weight loss, research shows that there is no single dietary strategy that is superior to others.9,10 For example, a recent trial, called the DIETFITS study, followed participants on either a low-fat or low-carbohydrate diet for one year and found no significant difference in weight loss between study groups. And both dietary strategies produced a range of weight loss results, with some participants losing over 60 pounds and others gaining 20 pounds over the course of the year, suggesting that what works for one individual may produce varying results in others.1

Figure 7.25. Results from the DIETFITS study show that regardless of the type of diet followed, participants experienced a similar wide range of changes in weight.

To learn more about the DIETFITS study, check out the following video.

VIDEO: “Stanford’s Christopher Gardner Tackles the Low-Carb vs. Low-Fat Question.” by Stanford Medicine, YouTube (February 19, 2018), 4:08 minutes.

The National Weight Control Registry (NWCR) has tracked over ten thousand people who have been successful in losing at least 30 pounds and maintaining this weight loss for at least one year. Their research findings show that 98 percent of participants in the registry modified their food intake, and 94 percent increased their physical activity, mainly by walking.11

Although there were a great variety of approaches taken by NWCR members to achieve successful weight loss, most have reported that their approach involved adhering to a low-calorie, low-fat diet and doing high levels of activity (about one hour of exercise per day). Moreover, most members eat breakfast every day, watch fewer than ten hours of television per week, and weigh themselves at least once per week. About half of them lost weight on their own, and the other half used some type of weight-loss program.11

In most scientific studies, successful weight loss is accomplished only by changing the diet and increasing physical activity together. Doing one without the other limits the amount of weight lost and the length of time that weight loss is sustained.12

Evidence-Based Dietary Recommendations

The 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans offers specific, evidence-based recommendations for dietary changes aimed at keeping calorie intake in balance with physical activity, which is key for weight management.13 These recommendations include following a healthy eating pattern that accounts for all foods and beverages within an appropriate calorie level, including the following:

- A variety of vegetables from all of the subgroups—dark green, red and orange, legumes (beans and peas), starchy, etc.

- Fruits, especially whole fruits

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grains

- Fat-free or low-fat dairy, including milk, yogurt, cheese, and/or fortified soy beverages

- A variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), and nuts, seeds, and soy products

- Oils, including vegetable oils and oils in foods, such as seafood and nuts

A healthy eating pattern also limits several components of public health concern in the U.S.:

- Consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from added sugars

- Consume less than 10 percent of calories per day from saturated fats

- Consume less than 2,300 milligrams (mg) per day of sodium

- If alcohol is consumed, it should be consumed in moderation—up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men—and only by adults of legal drinking age.

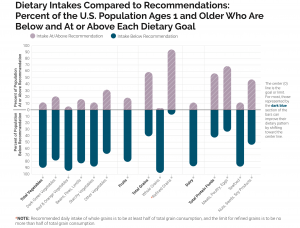

While these guidelines establish basic recommendations for dietary intake across all food groups, most Americans do not achieve these recommendations. Figure 9.26 shows how Americans are falling short of meeting the recommendations for vegetables, fruit, whole grains, dairy, and seafood and consume well over the recommended amount for refined grains. Meanwhile, many Americans also exceed the recommended limits for added sugars, saturated fats, sodium, and alcohol. Shifting towards more nutrient-dense choices, as recommended in the Dietary Guidelines, would help balance caloric intake and better meet nutrient needs for optimal health.

Figure 7.26. This graph indicates the percentage of the U.S. population ages 1 year and older with intakes below the recommendation or above the limit for different food groups and dietary components.

Evidence-Based Physical Activity Recommendations

The other part of the energy balance equation is physical activity. The Dietary Guidelines are complemented by the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, issued by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in an effort to provide evidence-based guidelines for appropriate physical activity levels. These guidelines provide recommendations to Americans aged three and older about how to improve health and reduce chronic disease risk through physical activity. Increased physical activity has been found to lower the risk of heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, colon, breast, and lung cancer, falls and fractures, depression, and early death. Increased physical activity not only reduces disease risk, but also improves overall health by increasing cardiovascular and muscular fitness, increasing bone density and strength, improving cognitive function, and assisting in weight loss and weight maintenance.14

The key guidelines for adults include the following:

- Adults should move more and sit less throughout the day. Some physical activity is better than none. Adults who sit less and do any amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity gain some health benefits.

- For substantial health benefits, adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) to 300 minutes (5 hours) per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) to 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity.

- Preferably, aerobic activity should be spread throughout the week.

- Engaging in physical activity beyond the equivalent of 300 minutes (5 hours) of moderate-intensity physical activity per week can result in additional health benefits and may help with weight loss and weight loss maintenance.

- Adults should also do muscle-strengthening activities of at least moderate intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days per week, as these activities provide additional health benefits. Exercises such as push-ups, sit-ups, squats, and lifting weights are all examples of muscle-strengthening activities.

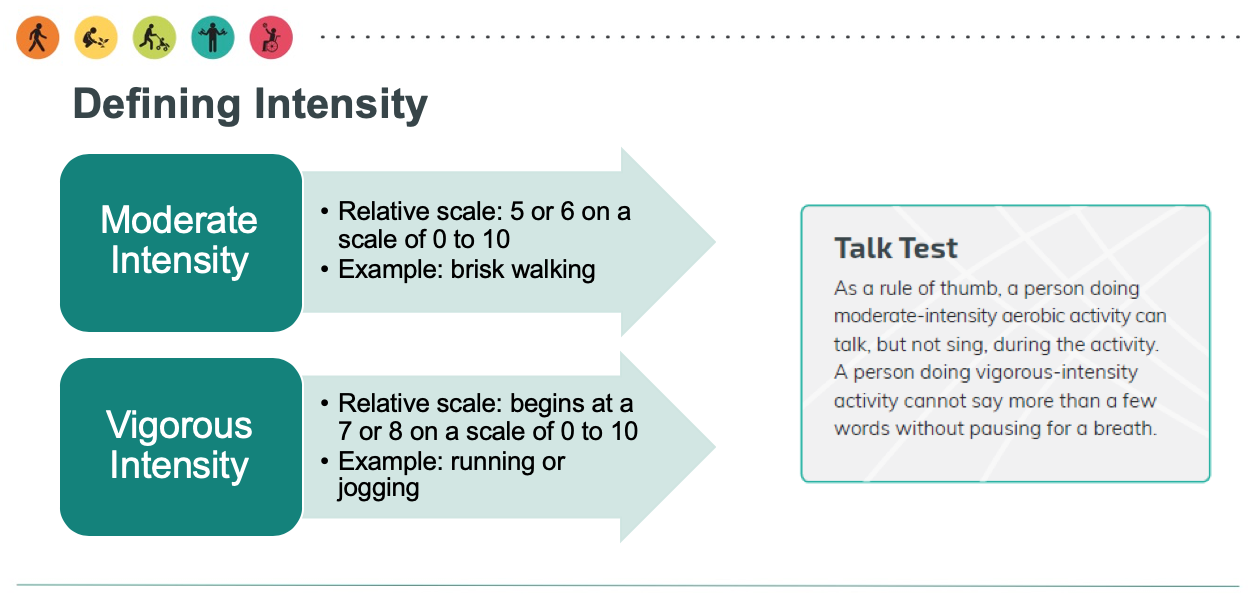

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines broadly classify moderate physical activities as those when you “can talk, but not sing, during the activity” and vigorous activities as those when you “cannot say more than a few words without pausing for a breath.”14 Despite the indisputable benefits of regular physical activity, a 2018 report from the American Heart Association estimates that 8 out of 10 Americans do not meet these guidelines.2

Figure 7.27. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines’ definition of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity exercise.

Given the number of Americans that are falling short on both nutrition and physical activity recommendations, it is easy to see that these two areas of behavior are of primary interest in improving the health and weight of our nation.

Evidence-Based Behavioral Recommendations

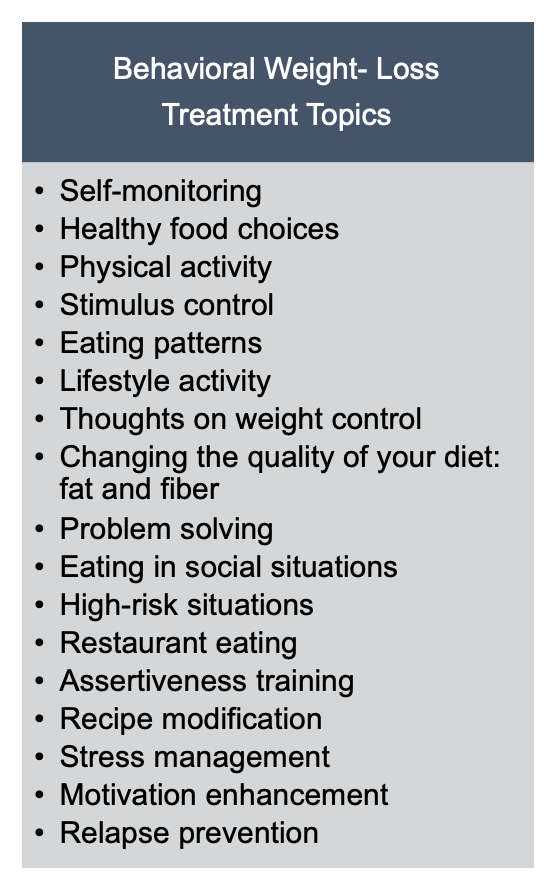

Behavioral weight loss interventions have been described as approaches “used to help individuals develop a set of skills to achieve a healthier weight. It is more than helping people to decide what to change; it is helping them identify how to change.”15 Cornerstones for these interventions typically include self-monitoring through daily recording of food intake and exercise, nutrition education and dietary changes, physical activity goals, and behavior modification.16 Research shows that these types of interventions can result in weight loss and a lower risk for type 2 diabetes, and similar maintenance strategies lead to less weight regained later.17

Behavioral interventions have been shown to help individuals achieve and maintain weight loss of at least 5 percent from baseline weight. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers a 5 percent weight loss to be clinically significant, as this level of weight loss has been shown to improve cardiometabolic risk factors such as blood lipid levels and insulin sensitivity.17,18 The behavioral intervention team often includes primary care clinicians, dietitians, psychologists, behavioral therapists, exercise physiologists, and lifestyle coaches.17 These programs may include a variety of delivery methods, often through group classes of 10-20 participants both in-person and online, and may use print-based or technology-based materials and resources. The interventions usually span one to two years with more frequent contact in the initial months (weekly to bi-monthly) followed by less frequent contact (monthly) in the latter months, or maintenance phase.17 A variety of behavioral topics are covered over the course of the program and range from nutrition education and goal-setting to problem-solving and assertiveness. Relapse prevention is included as participants move into the maintenance phase.16

Figure 7.28. Common topics included in behavioral interventions for weight loss, adapted from Smith, C. E., & Wing, R. R. (2000). New directions in behavioral weight-loss programs. Diabetes Spectrum, 13(3), 142-148.

Pharmacotherapy and Bariatric Surgery

In some situations, lifestyle changes in diet, exercise, and behavior modification are not enough to produce meaningful levels of weight loss, and the use of medications may be considered to improve weight loss outcomes. The use of medications is recommended in conjunction with, and not in place of, lifestyle changes. Medications are typically considered for individuals with a BMI over 30, or BMI over 27 with at least one coexisting condition, such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, or hypertension. Only medications approved by the FDA for weight loss should be used.19 Over-the-counter weight loss supplements are not monitored by the FDA and are not recommended due to safety concerns.

Surgical interventions may be appropriate for individuals with a BMI over 40 or BMI over 35 with obesity-related coexisting conditions, so long as they’re motivated to lose weight and behavioral interventions (with or without medication) have not been effective. Potential candidates for surgery should be referred to an experienced bariatric surgeon for consultation and evaluation.19

Non-Diet Approaches

In addition to weight management approaches that focus on the energy balance equation through dietary changes, physical activity programs, and behavioral interventions, there is a growing movement for non-diet approaches for a healthier mentality toward weight, food, and body image. These approaches focus on establishing healthier relationships with food and more body acceptance and positivity regardless of shape and size. Many of these programs seek to normalize relationships with food, make eating an enjoyable experience focused on well-being rather than dieting, do away with shame or guilt often associated with failed weight loss efforts, and promote respect and inclusivity for all people regardless of weight or size. Mindful eating or intuitive eating are common components of these approaches.

One of these approaches, the Satter Eating Competence Model, is based on four components: eating attitudes, food acceptance, regulation of food intake and body weight, and management of the eating context. According to Ellyn Satter, a registered dietitian and family therapist and the founder of the model, competent eaters are “confident, comfortable, and flexible with eating and are matter-of-fact and reliable about getting enough to eat of enjoyable and nourishing food.”20 This approach enhances “the importance of eating by making it positive, joyful, and intrinsically rewarding.”20 This model emphasizes that by developing a healthier relationship with food, individuals will yield the following benefits:21

- Have better diets

- Feel more positive about food and eating

- Have better overall health

- Have the same or lower BMI

- Sleep better

- Be more active

- Have better physical self-acceptance

- Be more trusting of themselves and others

Health at Every Size (HAES) is another movement started by the Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH) organization as an alternative to weight-centered health models. HAES aims to decrease our culture’s obsession with body size and weight, decrease weight discrimination and stigma, and instead promote size acceptance and inclusivity.22 Key principles of the HAES approach include:

- Acceptance and respect for the inherent diversity of body shapes and sizes

- Health enhancement through policies and services that promote well-being in all aspects of health, including physical, economic, social, emotional, and spiritual needs

- Respectful care and elimination of weight bias and discrimination through proper education and training

- Eating behaviors driven by hunger, satiety, nutritional needs, and pleasure instead of external regulation by diets and eating plans

- Physical activity through life-enhancing movement for all sizes and

abilities

To learn more about non-dieting approaches for a healthy lifestyle, check out the following video.

VIDEO: “Why Dieting Doesn’t Usually Work,”from TED, 12:30 minutes.

Self-Check

Attributions:

- University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program, “Dietary, Behavioral, and Physical Activity Recommendations for Weight Management,” CC BY-NC 4.0

References:

- 1Obesity and overweight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved November 13, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm.

- 2Han L, You D, Zeng F, et al. Trends in Self-perceived Weight Status, Weight Loss Attempts, and Weight Loss Strategies Among Adults in the United States, 1999-2006. (2019). JAMA Network Open. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15219

- 3Wing, R. R., & Hill, J. O. (2001). Successful weight loss maintenance. Annual review of nutrition, 21(1), 323-341.

- 4Kraschnewski, J. L., Boan, J., Esposito, J., Sherwood, N. E., Lehman, E. B., Kephart, D. K., & Sciamanna, C. N. (2010). Long-term weight loss maintenance in the United States. International journal of obesity, 34(11), 1644-1654. Retrieved November 8, 2019, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20479763.

- 5MacLean, P. S., Bergouignan, A., Cornier, M. A., & Jackman, M. R. (2011). Biology’s response to dieting: the impetus for weight regain. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 301(3), R581-R600. https://www.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpregu.00755.2010.

- 6Reinhardt, M., Thearle, M. S., Ibrahim, M., Hohenadel, M. G., Bogardus, C., Krakoff, J., & Votruba, S. B. (2015). A human thrifty phenotype associated with less weight loss during caloric restriction. Diabetes, 64(8), 2859-2867. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from https://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/64/8/2859.

- 7NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2015, May 11). Ease of weight loss influenced by individual biology. ScienceDaily. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/05/150511162918.htm

- 8Rosenbaum, M., Kissileff, H. R., Mayer, L. E., Hirsch, J., & Leibel, R. L. (2010). Energy intake in weight-reduced humans. Brain research, 1350, 95-102. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2926239/

- 9Treatment for overweight & obesity. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Retrieved November 10, 2019, from

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/treatment. - 10Gardner, C. D., Trepanowski, J. F., Del Gobbo, L. C., Hauser, M. E., Rigdon, J., Ioannidis, J. P., … & King, A. C. (2018). Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: the DIETFITS randomized clinical trial. Jama, 319(7), 667-679. Retrieved November 13, 2019, from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2673150.

- 11Research Findings. The National Weight Control Registry. Retrieved November 8, 2019, from

http://www.nwcr.ws/Research/default.htm. - 12National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, & Kidney Diseases (US). (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report (No. 98). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 51S–210S.

- 13U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, 9th Edition. Retrieved from https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/

- 142018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved November 11, 2019, from https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/.

- 15Yanovski, S. (2017, December). The challenge of treating obesity and overweight: Proceedings of a workshop. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board. Roundtable on Obesity Solutions, Washington (DC). Retrieved November 13, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK475856/.

- 16Smith, C. E., & Wing, R. R. (2000). New directions in behavioral weight-loss programs. Diabetes Spectrum, 13(3), 142-148. Retrieved November 13, 2019, from http://journal.diabetes.org/diabetesspectrum/00v13n3/pg142.htm.

- 17Curry, S. J., Krist, A. H., Owens, D. K., Barry, M. J., Caughey, A. B., Davidson, K. W., … & Kubik, M. (2018). Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama, 320(11), 1163-1171.

- 18Donnelly, J. E., Blair, S. N., Jakicic, J. M., Manore, M. M., Rankin, J. W., & Smith, B. K. (2009). Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 41(2), 459-471.

- 19Jensen, M. D., Ryan, D. H., Apovian, C. M., Ard, J. D., Comuzzie, A. G., Donato, K. A., … & Loria, C. M. (2014). 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 63(25 Part B), 2985-3023.

- 20Satter, E. (2007). Eating competence: Nutrition education with the Satter eating competence model. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 39(5), S189-S194. Retrieved November 12, 2019, from

https://www.jneb.org/article/S1499-4046(07)00467-8/abstract. - 21The Satter Eating Competence Model. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from

https://www.ellynsatterinstitute.org/satter-eating-competence-model/. - 22The Health at Every Size Approach. Association for Size Diversity and Health. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from https://www.sizediversityandhealth.org/content.asp?id=152.

Image Credits:

- “Individuals with Obesity” by Obesity Canada is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

- Figure 7.24. Thrifty vs spendthrift genes. Fig. 1. Reinhardt, M., Thearle, M. S., Ibrahim, M., Hohenadel, M. G., Bogardus, C., Krakoff, J., & Votruba, S. B. (2015). A human thrifty phenotype associated with less weight loss during caloric restriction. Diabetes, 64(8), 2859-2867.

- Figure 7.25.“DIETFITS Study” by Journal of the American Medical Association is in the Public Domain

- Figure 7.26. “Dietary Intakes Compared to Recommendations” from Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, Figure 1-6 is in the Public Domain

- Figure 7.27. “Exercise Intensity” by Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion is in the Public Domain

- Figure 7.28. “Behavioral Weight-Loss Treatment Topics” by Heather Leonard is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- “Women Eating” by Obesity Canada is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.

Interventions that help individuals develop skills that support healthy lifestyle and body weight.

Approaches that focus on establishing a healthy relationship with food and more body acceptance and positivity regardless of shape and size (e.g: Satter Eating Competence Model, Health at Every Size).

A model developed by Ellyn Satter; focuses on eating attitudes, food acceptance, regulation of food intake and body weight, and management of the eating context.

An approach that aims to decrease our culture’s obsession with body size and weight, decrease weight discrimination and stigma, and instead promote size acceptance and inclusivity.