Dietary Supplements

By now you know that a balanced, nutritious diet is important for good health. But you may also wonder if your diet is adequate, or if you could benefit from taking a vitamin or mineral supplement. You may also be curious about other supplements that claim to help you lose weight, build muscle, ease joint pain, or help build good bacteria in your gut.

According to the results of a large national survey published in JAMA in 2016, 52% of U.S. adults reported using supplements in 2011-2012.2 With over half of Americans reporting dietary supplement use, it’s important to have a conversation about the safety and efficacy of these products. Are dietary supplements safe? Are they effective? Do Americans need a multivitamin/mineral supplement? If so, what are the guidelines and recommendations for choosing a supplement? We will explore these important questions in this section.

Regulation of Dietary Supplements

A dietary supplement is defined as a product that:1

- is intended to supplement the diet

- contains one or more dietary ingredients (e.g., vitamins, minerals, herbs or other botanicals, amino acids, and enzymes)

- can be taken by mouth as a pill, capsule, tablet, or liquid

- is labeled as being a dietary supplement

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates dietary supplements, but under a different set of regulations than foods, pharmaceuticals, and over-the-counter drugs. In 1994, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) created new regulations for the labeling and safety of dietary supplements. Under these rules, the “FDA is not authorized to review dietary supplement products for safety and effectiveness before they are marketed.”3 Therefore, the responsibility falls on the manufacturers and distributors of dietary supplements to ensure their products are safe before they go to consumers. The FDA has to prove that the product is unsafe in order to remove it from the market. This is a big contrast from pharmaceuticals, which must obtain approval from the FDA, showing substantial evidence that their drugs are safe and effective before reaching the marketplace.

The FDA issued Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) for dietary supplements in 2007. GMPs are a set of requirements and expectations by which dietary supplements must be manufactured, prepared, and stored to ensure quality.4 Manufacturers are expected to guarantee the identity, purity, strength, and composition of their dietary supplements.4

Once a dietary supplement is on the market, the FDA tracks side effects reported by consumers, supplement companies, and others. If the FDA finds a product to be unsafe, it can take legal action against the manufacturer or distributor and may issue a warning or require that the product be removed from the marketplace. However, the FDA says it can’t test all products marketed as dietary supplements that may have potentially harmful hidden ingredients.

Safety of Dietary Supplements

With current regulations, the safety of dietary supplements is the manufacturers’ responsibility. Unfortunately, manufacturers don’t always have the public’s best interest in mind, especially when there is a profit to be gained.

According to the FDA website, the “FDA has found that manufacturing problems have been associated with dietary supplements. Products have been recalled because of microbiological, pesticide, and heavy metal contamination and because they do not contain the dietary ingredients they are represented to contain or they contain more or less than the amount of the dietary ingredient claimed on the label.”2

What this means for consumers is that they should use caution when considering whether to use a dietary supplement. Keep in mind the following information from the Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at the National Institutes of Health:1

- What’s on the label may not be what is in the product. For example, the FDA has found prescription drugs, including anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin), anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin), and others, in products being sold as dietary supplements. You can see a list of some of those products on the FDA’s Tainted Supplements webpage.

- Supplement labels may make illegal claims to make their product more appealing. A 2012 Government study of 127 dietary supplements marketed for weight loss or to support the immune system found that 20 percent made illegal claims.

- Dietary supplements can interact with other medications, and cause harm. For example, the herbal supplement St. John’s wort makes many medications less effective.

- The term natural does not always mean safe. Ephedra, an evergreen plant native to central Asia is associated with heart problems and risk of death. In 2004, the FDA banned the sale of ephedrine in dietary supplements for these reasons. Supplements can contain natural herbs and other plant-based ingredients that have not been adequately studied. We don’t know if supplement ingredients are dangerous until people end up really sick or even die from them. Dietary supplements result in an estimated 23,000 emergency room visits every year in the United States, according to a 2015 study. Many of the patients are young adults having heart problems from weight-loss or energy products and older adults having swallowing problems from taking large vitamin pills.

- The term “standardized” (or “verified” or “certified”) on a supplement does not always guarantee product quality or safety. These are terms used by manufacturers to sell their product and have not been legally defined.

You can report safety concerns about a dietary supplement through the U.S. Health and Human Services Safety Reporting Portal. For more information on contaminants in dietary supplements, visit the FDA’s Dietary Supplement Products & Ingredients webpage.

Efficacy of Dietary Supplements

The amount of scientific evidence on dietary supplements varies widely—there is a lot of information on some and very little on others. The Center for Complementary and Integrative Health at the National Institutes of Health offers these key points about efficacy of dietary supplements:1

- Dietary supplements can’t be marketed with claims that they can diagnose, treat, cure, mitigate, or prevent any disease; such claims would require the product to be approved by the FDA as a pharmaceutical. Instead, dietary supplements are marketed with health claims or structure/function claims, similar to claims on food labels. Recall from Unit 1 that structure/function claims (e.g., “builds strong bones,” or “boosts immunity”) are intentionally vague and require no evidence to support them. Supplements are often labeled with claims that have little to no scientific basis.

- Studies have found that some dietary supplements may have benefits, such as melatonin for jet lag. Others may have little or no benefit, such as ginkgo for dementia.1 Many dietary supplements haven’t been studied at all in humans.

- Studies of many supplements haven’t supported claims made about them. For example, in several studies, echinacea didn’t help cure colds and Ginkgo biloba wasn’t useful for dementia—but you can still find Ginkgo biloba supplements with claims that they improve memory and echinacea supplements with claims of providing “immune support.” Many times the research on a dietary supplement is conflicting, such as whether the supplements glucosamine and chondroitin improve symptoms of osteoarthritis.1 Research design and interpretation can also be biased when funded by the supplement industry.

- Most research shows that taking multivitamin/mineral (MVM) supplements doesn’t result in living longer, slowing cognitive decline, or lowering the chance of getting cancer, heart disease, or diabetes. However, taking a multivitamin is unlikely to pose health risks, providing you follow the guidelines below for choosing supplements.1

Guidelines for Choosing Supplements

Throughout this text, we have discussed the importance of whole foods. As you might suspect, supplements can not replace real, whole food. Marion Nestle, professor emerita at New York University and author of many books about nutrition, wrote eloquently about the benefits of getting nutrients from food instead of supplements in a 2006 blog post:

“Unless you have been diagnosed with a vitamin or mineral deficiency and need to replenish that nutrient in a great big hurry, it is always better to get nutrients from foods—the way nature intended. I can think of three benefits of whole foods as compared to supplements:

(1) you get the full variety of nutrients—vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, etc–in that food, not just the one nutrient in the supplement;

(2) the amounts of the various nutrients are balanced so they don’t interfere with each other’s digestion, absorption, or metabolism; and

(3) there is no possibility of harm from taking nutrients from foods (OK. Polar bear liver is an exception; its level of vitamin A is toxic).

In contrast, high doses of single nutrients not only fail to improve health but also can make things worse, as has been shown in some clinical trials of the effects of beta-carotene, vitamin E, and folic acid, for example, on heart disease or cancer. And foods taste a whole lot better, of course.”5

However, there are certain populations that might be at risk for developing nutrient deficiencies, and they may benefit from a MVM supplement or supplements of specific nutrients. These groups include the elderly, strict vegetarians or vegans, people restricting their caloric intake, pregnant women, or individuals with food insecurity.6

If you choose to take supplements, keep moderation in mind, and use the following guidelines to help you choose a supplement.

1. Don’t substitute for whole foods. According to the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, “Because foods provide an array of nutrients and other components that have benefits for health, nutritional needs should be met primarily through foods.”7 Whole foods are complex and not only contain essential vitamins and minerals, but also dietary fiber and phytochemicals that may have positive health benefits. As their name suggests, supplements should never act as replacements for whole food, but rather as supplements to fill in some nutritional gaps.

2. Check the dose carefully. Since dietary supplements are not regulated before they hit the market, it is not uncommon to find nutrient levels that exceed the upper intake level (UL). A good rule-of-thumb is to choose a supplement that keeps the dose close to 100% of the Daily Value (unless advised by a doctor to help correct a deficiency) and definitely no more than the UL.

3. If getting supplements from multiple sources, make sure you add together the doses. Supplements not only come in pill form, but also powder and liquid form. Vitamin water, protein powder, and other products like Emergen-C are often fortified with large amounts of vitamins and minerals.

4. Be skeptical of product claims. Remember that supplement manufacturers promote their products with structure/function claims, and they don’t have to provide any evidence that the product actually does what it claims to do. If something sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

5. Look for third-party testing when purchasing a supplement. ConsumerLab.com, NSF International, U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP), and UL are all companies that do third-party testing on dietary supplements.8 If you see these companies’ stamps (see Figure 8.5) on a supplement bottle, it means that the product is periodically tested to check that it:

-

- Contains the ingredients listed on the label, in the declared potency and amounts.

- Does not contain harmful levels of specified contaminants (e.g., heavy metals and pesticides).

- Will break down and release into the body within a specified amount of time. (If a supplement does not break down properly to allow its ingredients to be available for absorption in the body, the consumer will not get the full benefit of its contents.)

Figure 8.5. The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) verification mark. USP is a nonprofit organization that does third-party testing on dietary supplements. This mark helps assure consumers that the product has been tested for quality, purity, potency, performance, and consistency.9

6. Choose a MVM supplement that is tailored to your age, sex, and other characteristics (e.g., pregnancy). This is important because different populations have different nutrient needs. MVMs for seniors typically provide more calcium and vitamin D for bone health than MVMs for younger adults. MVMs for women contain more iron than MVMs for men. Prenatal supplements generally provide no vitamin A as retinol, and most children’s MVMs provide age-appropriate amounts of nutrients.10

7. Check with your healthcare provider to ensure the supplement you are considering is safe for you. Supplements can interact with both prescription medications and over-the-counter medications potentially causing life-threatening complications.

Self-Check:

References:

- 1National Institutes of Health Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Using Dietary Supplements Wisely. Retrieved April 1, 2020, from https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/using-dietary-supplements-wisely

- 2Kantor E.D., Rehm C.D., Du M., White E., Giovannucci E.L. (2016). Trends in dietary supplement use among US adults from 1999–2012. JAMA, 316, 1464–1474. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14

- 3Information for Consumers Using Dietary Supplements. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2020, from https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements/inf ormation-consumers-using-dietary-supplements

- 4What You Need to Know About Dietary Supplements. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved April 1, 2020 from https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/what-you-need-know-about-dietary-supplements?utm_campaign=buffer&utm_content=buffer6d184&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com

- 5Nestle, M. (2007). Food vs. Supplements. Food Politics. Retrieved from https://www.foodpolitics.com/2007/06/foods-vs-supplements/

- 6Vitamins Minerals and Supplements: Do You Need to Take Them? Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Retrieved April 1, 2020, from https://www.eatright.org/food/vitamins-and-supplements/dietary-supplements/vitamins-minerals-and-supplements-do-you-need-to-take-them

- 7U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, 9th Edition. Retrieved from https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/

- 8Loria, K. (2019, October 30). How To Choose Supplements Wisely. Consumer Reports. Retrieved from https://www.consumerreports.org/supplements/how-to-choose-supplements-wisely/

- 9Dietary Supplements Verification Program. USP. Retrieved April 3, 2020, from https://www.usp.org/verification-services/dietary-supplements-verification-program

- 10Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Retrieved April 3, 2020, from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/MVMS-HealthProfessional/

Images:

- Woman holding probiotic capsule photo by Daily Nouri on Unsplash (license information)

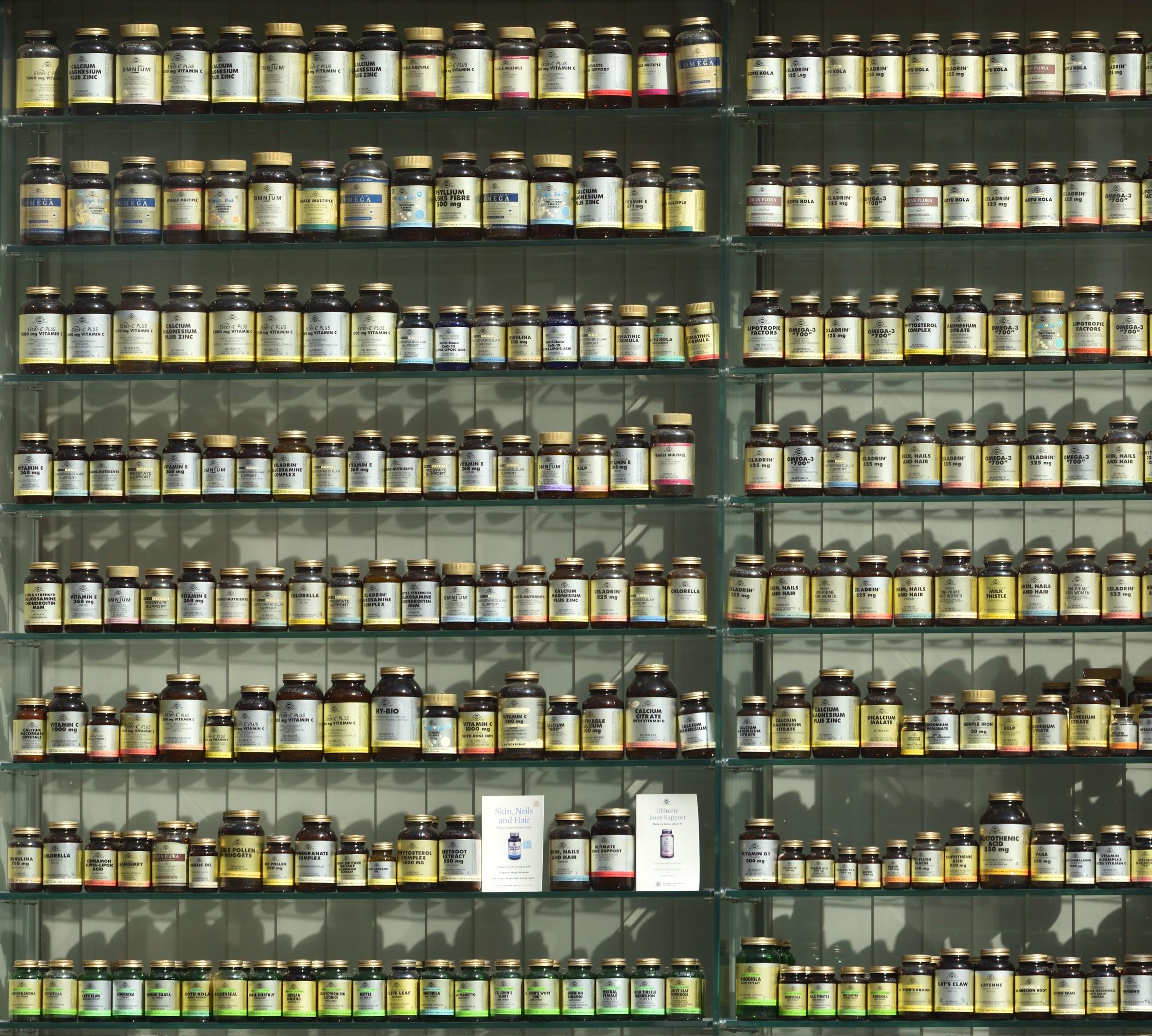

- Supplement photo by Angel Sinigersky on Unsplash (license information)

- Figure 8.5. “USP Verification Mark” by USP is used with permission

A product that is intended to supplement the diet and can be taken by mouth; contains one or more dietary ingredients (e.g., vitamins, minerals, herbs or other botanicals, amino acids, or enzymes).