Control of the Cell Cycle

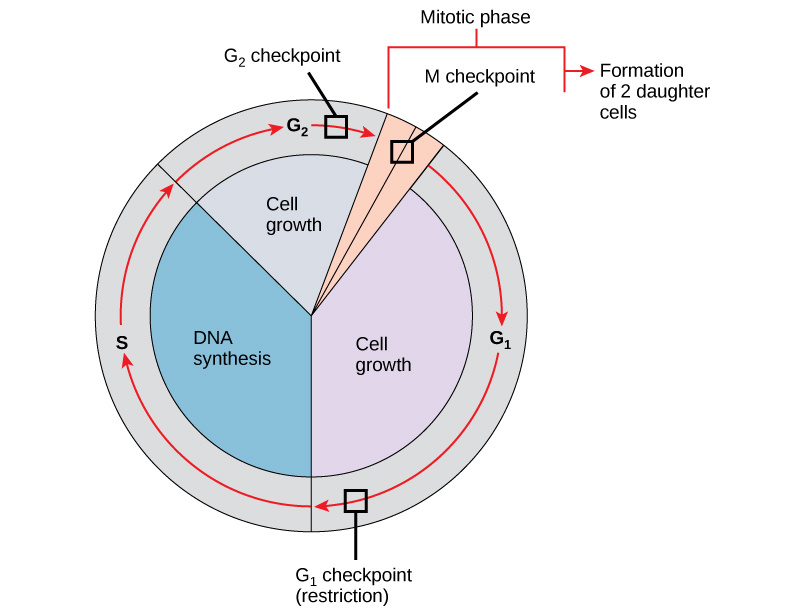

It is essential that daughter cells be exact duplicates of the parent cell. Mistakes in the duplication or distribution of the chromosomes lead to mutations that may be passed forward to every new cell produced from the abnormal cell. To prevent a compromised cell from continuing to divide, there are internal control mechanisms that operate at three main cell cycle checkpoints at which the cell cycle can be stopped until conditions are favorable.

The first checkpoint (G1) determines whether all conditions are favorable for cell division to proceed. This checkpoint is the point at which the cell irreversibly commits to the cell-division process. In addition to adequate reserves and cell size, there is a check for damage to the genomic DNA. A cell that does not meet all the requirements will not be released into the S phase.

The second checkpoint (G2) bars the entry to the mitotic phase if certain conditions are not met. The most important role of this checkpoint is to ensure that all of the chromosomes have been replicated and that the replicated DNA is not damaged.

The final checkpoint (M) occurs in the middle of mitosis. This checkpoint determines if all of the copied chromosomes are arranged appropriately to be separated to opposite sides of the cell. If this doesn’t happen correctly, incorrect numbers of chromosomes can be partitioned into each of the daughter cells, which would likely cause them to die.

Regulator Molecules of the Cell Cycle

In addition to the internally controlled checkpoints, there are two groups of intracellular molecules that regulate the cell cycle. These regulatory molecules either promote progress of the cell to the next phase (positive regulation) or halt the cycle (negative regulation). Regulator molecules may act individually, or they can influence the activity or production of other regulatory proteins. Therefore, it is possible that the failure of a single regulator may have almost no effect on the cell cycle, especially if more than one mechanism controls the same event. It is also possible that the effect of a deficient or non-functioning regulator can be wide-ranging and possibly fatal to the cell if multiple processes are affected.

Positive Regulation of the Cell Cycle

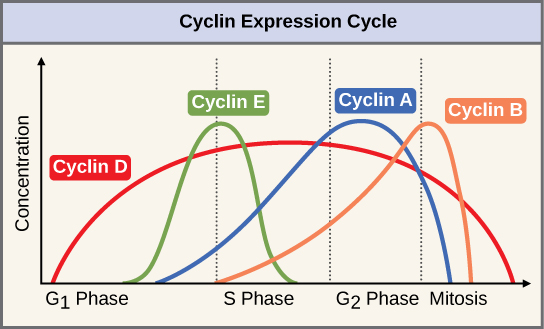

Two groups of proteins, called cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), are responsible for the progress of the cell through the various checkpoints. The levels of the four cyclin proteins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle in a predictable pattern (Figure 2). Increases in the concentration of cyclin proteins are triggered by both external and internal signals. After the cell moves to the next stage of the cell cycle, the cyclins that were active in the previous stage are degraded.

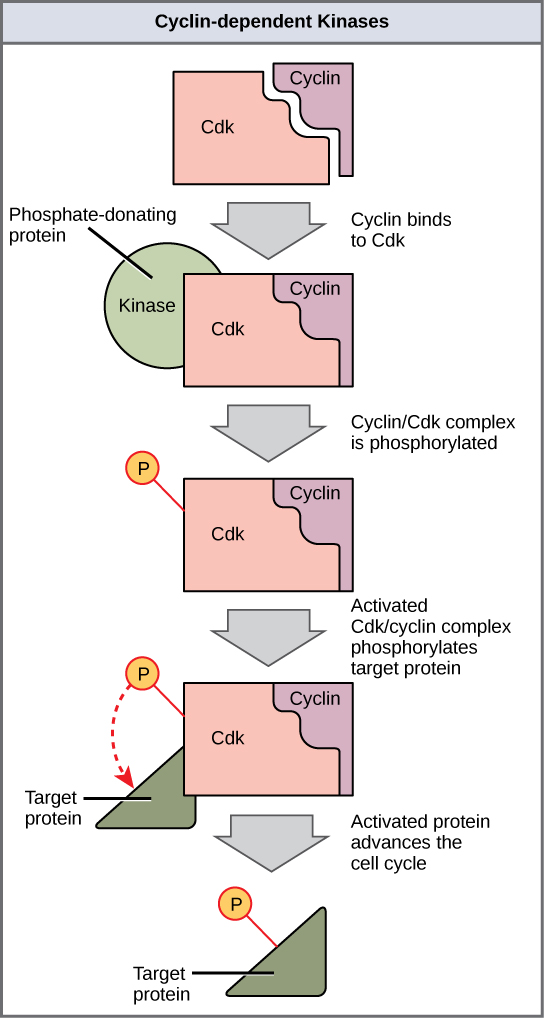

Cyclins regulate the cell cycle only when they are tightly bound to Cdks. To be fully active, the Cdk/cyclin complex must also be phosphorylated in specific locations. Like all kinases, Cdks are enzymes (kinases) that phosphorylate other proteins. Phosphorylation activates the protein by changing its shape. The proteins phosphorylated by Cdks are involved in advancing the cell to the next phase (Figure 3). The levels of Cdk proteins are relatively stable throughout the cell cycle; however, the concentrations of cyclin fluctuate and determine when Cdk/cyclin complexes form. The different cyclins and Cdks bind at specific points in the cell cycle and thus regulate different checkpoints.

Since the cyclic fluctuations of cyclin levels are based on the timing of the cell cycle and not on specific events, regulation of the cell cycle usually occurs by either the Cdk molecules alone or the Cdk/cyclin complexes. Without a specific concentration of fully activated cyclin/Cdk complexes, the cell cycle cannot proceed through the checkpoints.

Negative Regulation of the Cell Cycle

The second group of cell cycle regulatory molecules are negative regulators. In positive regulation, active molecules such as CDK/cyclin complexes cause the cell cycle to progress. In negative regulation, active molecules halt the cell cycle.

The best understood negative regulatory molecules are retinoblastoma protein (Rb), p53, and p21. Much of what is known about cell cycle regulation comes from research conducted with cells that have lost regulatory control. All three of these regulatory proteins were discovered to be damaged or non-functional in cells that had begun to replicate uncontrollably (became cancerous). In each case, the main cause of the unchecked progress through the cell cycle was a faulty copy of the regulatory protein. For this reason, Rb and other proteins that negatively regulate the cell cycle are sometimes called tumor suppressors.

Rb, p53, and p21 act primarily at the G1 checkpoint. p53 is a multi-functional protein that has a major impact on the commitment of a cell to division because it acts when there is damaged DNA in cells that are undergoing the preparatory processes during G1. If damaged DNA is detected, p53 halts the cell cycle and recruits enzymes to repair the DNA. If the DNA cannot be repaired, p53 can trigger apoptosis, or cell suicide, to prevent the duplication of damaged chromosomes. As p53 levels rise, the production of p21 is triggered. p21 enforces the halt in the cycle dictated by p53 by binding to and inhibiting the activity of the Cdk/cyclin complexes. As a cell is exposed to more stress, higher levels of p53 and p21 accumulate, making it less likely that the cell will move into the S phase.

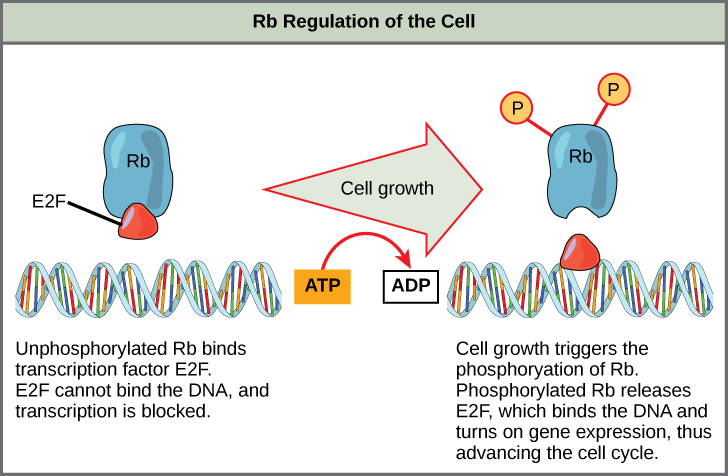

Rb exerts its regulatory influence on other positive regulator proteins. Chiefly, Rb monitors cell size. In the active, dephosphorylated state, Rb binds to proteins called transcription factors (Figure 4). Transcription factors “turn on” specific genes, allowing the production of proteins encoded by that gene. When Rb is bound to transcription factors, production of proteins necessary for the G1/S transition is blocked. As the cell increases in size, Rb is slowly phosphorylated until it becomes inactivated. Rb releases the transcription factors, which can now turn on the gene that produces the transition protein, and this particular block is removed. For the cell to move past each of the checkpoints, all positive regulators must be “turned on,” and all negative regulators must be “turned off.”

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 27, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.10:Vbi92lHB@9/The-Cell-Cycle

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 27, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.10:LlKfCy5H@4/Prokaryotic-Cell-Division