Whole Genome Sequencing

Although there have been significant advances in the medical sciences in recent years, doctors are still confounded by some diseases, and they are using whole-genome sequencing to get to the bottom of the problem. Whole-genome sequencing is a process that determines the DNA sequence of an entire genome. Whole-genome sequencing is a brute-force approach to problem solving when there is a genetic basis at the core of a disease. Several laboratories now provide services to sequence, analyze, and interpret entire genomes.

For example, whole-exome sequencing is a lower-cost alternative to whole genome sequencing. In exome sequencing, only the coding, exon-producing regions of the DNA are sequenced. In 2010, whole-exome sequencing was used to save a young boy whose intestines had multiple mysterious abscesses. The child had several colon operations with no relief. Finally, whole-exome sequencing was performed, which revealed a defect in a pathway that controls apoptosis (programmed cell death). A bone-marrow transplant was used to overcome this genetic disorder, leading to a cure for the boy. He was the first person to be successfully treated based on a diagnosis made by whole-exome sequencing. Today, human genome sequencing is more readily available and can be completed in a day or two for about $1000.

Strategies Used in Sequencing Projects

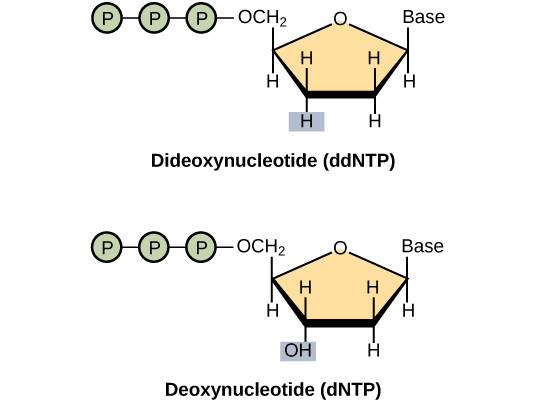

The basic sequencing technique used in all modern day sequencing projects is the chain termination method (also known as the dideoxy method), which was developed by Fred Sanger in the 1970s. The chain termination method involves DNA replication of a single-stranded template with the use of a primer and a regular deoxynucleotide (dNTP), which is a monomer, or a single unit, of DNA. The primer and dNTP are mixed with a small proportion of fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs). The ddNTPs are monomers that are missing a hydroxyl group (–OH) at the site at which another nucleotide usually attaches to form a chain (Figure 1).

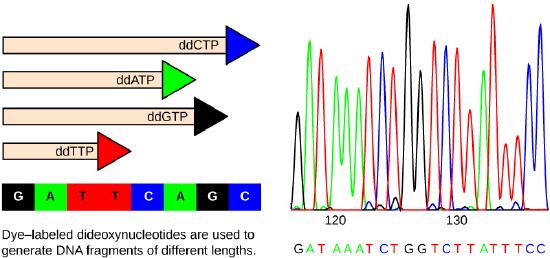

Each ddNTP is labeled with a different color of fluorophore. Every time a ddNTP is incorporated in the growing complementary strand, it terminates the process of DNA replication, which results in multiple short strands of replicated DNA that are each terminated at a different point during replication. When the reaction mixture is processed by gel electrophoresis after being separated into single strands, the multiple newly replicated DNA strands form a ladder because of the differing sizes. Because the ddNTPs are fluorescently labeled, each band on the gel reflects the size of the DNA strand and the ddNTP that terminated the reaction. The different colors of the fluorophore-labeled ddNTPs help identify the ddNTP incorporated at that position. Reading the gel on the basis of the color of each band on the ladder produces the sequence of the template strand (figure 2)

Early Strategies: Shotgun Sequencing and Pair-Wise End Sequencing

In shotgun sequencing method, several copies of a DNA fragment are cut randomly into many smaller pieces (somewhat like what happens to a round shot cartridge when fired from a shotgun). All of the segments are then sequenced using the chain-sequencing method. Then, with the help of a computer, the fragments are analyzed to see where their sequences overlap. By matching up overlapping sequences at the end of each fragment, the entire DNA sequence can be reformed. A larger sequence that is assembled from overlapping shorter sequences is called a contig. As an analogy, consider that someone has four copies of a landscape photograph that you have never seen before and know nothing about how it should appear. The person then rips up each photograph with their hands, so that different size pieces are present from each copy. The person then mixes all of the pieces together and asks you to reconstruct the photograph. In one of the smaller pieces you see a mountain. In a larger piece, you see that the same mountain is behind a lake. A third fragment shows only the lake, but it reveals that there is a cabin on the shore of the lake. Therefore, from looking at the overlapping information in these three fragments, you know that the picture contains a mountain behind a lake that has a cabin on its shore. This is the principle behind reconstructing entire DNA sequences using shotgun sequencing.

Originally, shotgun sequencing only analyzed one end of each fragment for overlaps. This was sufficient for sequencing small genomes. However, the desire to sequence larger genomes, such as that of a human, led to the development of double-barrel shotgun sequencing, more formally known as pairwise-end sequencing. In pairwise-end sequencing, both ends of each fragment are analyzed for overlap. Pairwise-end sequencing is, therefore, more cumbersome than shotgun sequencing, but it is easier to reconstruct the sequence because there is more available information.

Next-generation Sequencing

Since 2005, automated sequencing techniques used by laboratories are under the umbrella of next-generation sequencing, which is a group of automated techniques used for rapid DNA sequencing. These automated low-cost sequencers can generate sequences of hundreds of thousands or millions of short fragments (25 to 500 base pairs) in the span of one day. These sequencers use sophisticated software to get through the cumbersome process of putting all the fragments in order.

Use of Whole-Genome Sequences of Model Organisms

The first genome to be completely sequenced was of a bacterial virus, the bacteriophage fx174 (5368 base pairs); this was accomplished by Fred Sanger using shotgun sequencing. Several other organelle and viral genomes were later sequenced. The first organism whose genome was sequenced was the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae; this was accomplished by Craig Venter in the 1980s. Approximately 74 different laboratories collaborated on the sequencing of the genome of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which began in 1989 and was completed in 1996, because it was 60 times bigger than any other genome that had been sequenced. By 1997, the genome sequences of two important model organisms were available: the bacterium Escherichia coli K12 and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genomes of other model organisms, such as the mouse Mus musculus, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the nematode Caenorhabditis. elegans, and humans Homo sapiens are now known. A lot of basic research is performed in model organisms because the information can be applied to genetically similar organisms. A model organism is a species that is studied as a model to understand the biological processes in other species represented by the model organism. Having entire genomes sequenced helps with the research efforts in these model organisms. The process of attaching biological information to gene sequences is called genome annotation. Annotation of gene sequences helps with basic experiments in molecular biology, such as designing PCR primers and RNA targets.

Uses of Genome Sequences

DNA microarrays are methods used to detect gene expression by analyzing an array of DNA fragments that are fixed to a glass slide or a silicon chip to identify active genes and identify sequences. Almost one million genotypic abnormalities can be discovered using microarrays, whereas whole-genome sequencing can provide information about all six billion base pairs in the human genome. Although the study of medical applications of genome sequencing is interesting, this discipline tends to dwell on abnormal gene function. Knowledge of the entire genome will allow future onset diseases and other genetic disorders to be discovered early, which will allow for more informed decisions to be made about lifestyle, medication, and having children. Genomics is still in its infancy, although someday it may become routine to use whole-genome sequencing to screen every newborn to detect genetic abnormalities.

In addition to disease and medicine, genomics can contribute to the development of novel enzymes that convert biomass to biofuel, which results in higher crop and fuel production, and lower cost to the consumer. This knowledge should allow better methods of control over the microbes that are used in the production of biofuels. Genomics could also improve the methods used to monitor the impact of pollutants on ecosystems and help clean up environmental contaminants. Genomics has allowed for the development of agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals that could benefit medical science and agriculture.

It sounds great to have all the knowledge we can get from whole-genome sequencing; however, humans have a responsibility to use this knowledge wisely. Otherwise, it could be easy to misuse the power of such knowledge, leading to discrimination based on a person’s genetics, human genetic engineering, and other ethical concerns. This information could also lead to legal issues regarding health and privacy.

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. January 2, 2017 https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.120:5l844Z38@7/Whole-Genome-Sequencing