DNA Structure

In the 1950s, Francis Crick and James Watson worked together to determine the structure of DNA at the University of Cambridge, England. Other scientists like Linus Pauling and Maurice Wilkins were also actively exploring this field. Pauling had discovered the secondary structure of proteins using X-ray crystallography. In Wilkins’ lab, researcher Rosalind Franklin was using X-ray diffraction methods to understand the structure of DNA. Watson and Crick were able to piece together the puzzle of the DNA molecule on the basis of Franklin’s data because Crick had also studied X-ray diffraction (Figure 1).

Watson and Crick gained access to Franklin’s data without her knowledge or approval. In 1962, James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Unfortunately, by then Franklin had died (of ovarian cancer, likely caused by exposure to X-rays), and Nobel prizes are not awarded posthumously (after death). Like most stories, there is a lot more to this that we’re not going to discuss, but it’s an important example of sexism in the sciences. The documentary “The Secret of Photo 51” is available on YouTube if you’d like to learn more.

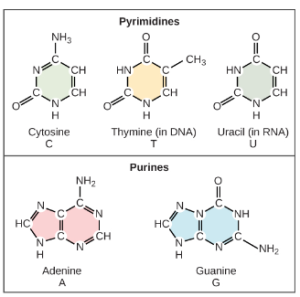

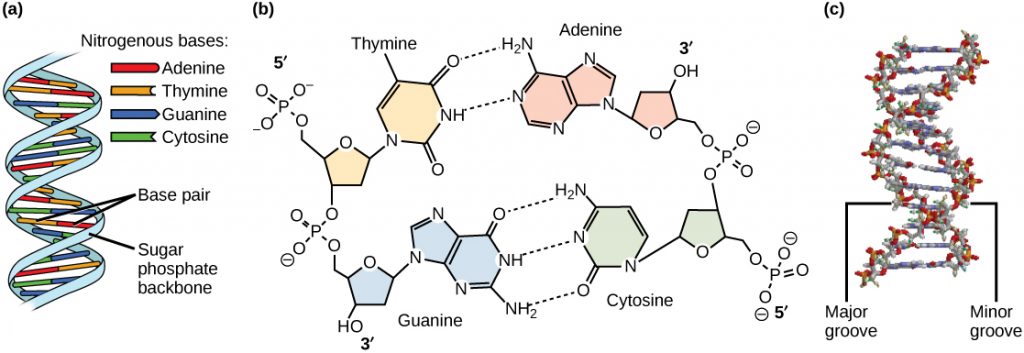

Based on Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray diffraction photograph, and work by other scientists, Watson and Crick proposed that DNA is made up of two strands of nucleotides that are twisted around each other to form a right-handed helix. The nucleotides are joined together in a chain by covalent bonds known as phosphodiester bonds. Scientists already knew that nucleotides contain the same three important components: a nitrogenous base, a deoxyribose (5-carbon sugar), and a phosphate group (Figure 2). The nucleotide is named depending on the nitrogenous base: adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). Adenine and guanine are both purines, while cytosine and thymine are pyrimidines. The purines have a double ring structure with a six-membered ring fused to a five-membered ring. Pyrimidines are smaller in size; they have a single six-membered ring structure. One good way to remember this is that cytosine, thymine, and pyrimidine all contain the letter “y”.

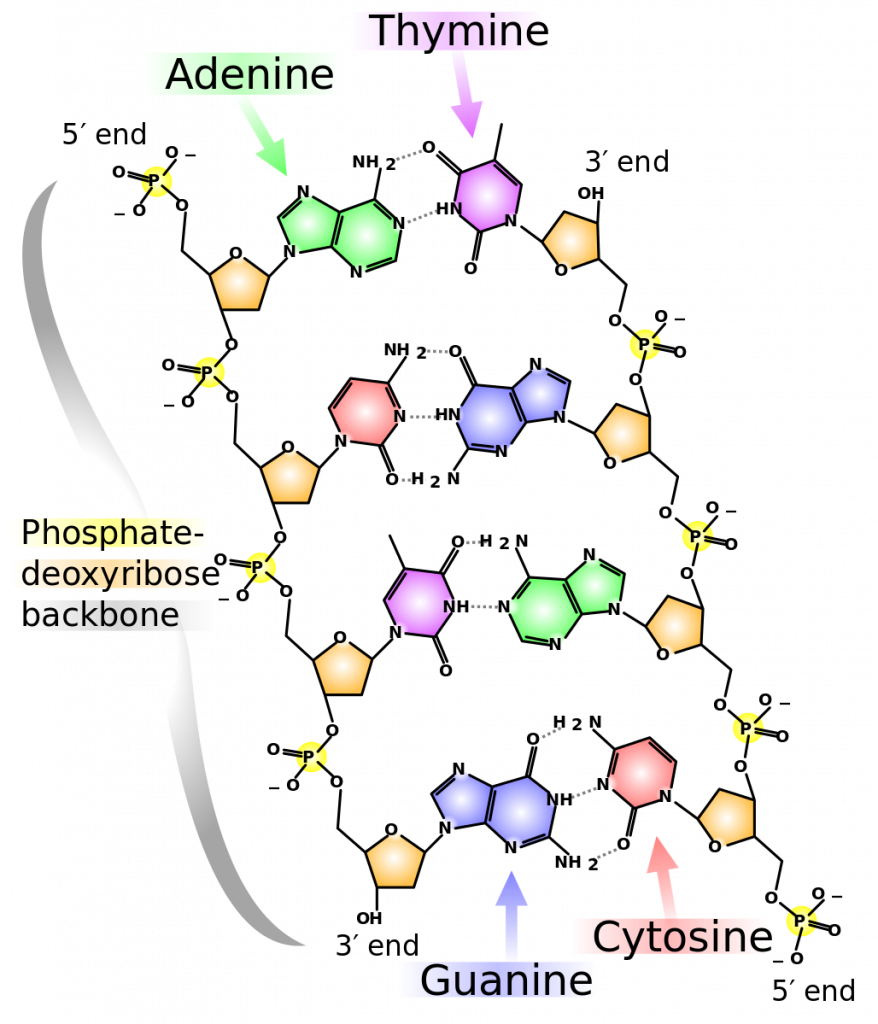

Watson and Crick’s model proposed that the two strands of nucleotides interact through base pairing between the nucleotides: A pairs with T and G pairs with C. Adenine and thymine are complementary base pairs, and cytosine and guanine are also complementary base pairs. The base pairs are stabilized by hydrogen bonds (a weak type of bond that forms between partially positive and partially negative atoms). Adenine and thymine form two hydrogen bonds and cytosine and guanine form three hydrogen bonds. Since a purine is “2 rings” across and a pyrimidine is “1 ring” across (Figure 2), the diameter of the DNA double helix remains constant at “3 rings” (Figure 3).

The carbon atoms of the five-carbon sugar are numbered in order starting from the carbon connected to the nitrogenous base: 1′, 2′, 3′, 4′, and 5′ (1′ is read as “one prime”). We don’t particularly care about the 1′, 2′, or 4′ positions – you’ll never hear them mentioned again. At the 3′ position, there is always a hydroxyl (OH) group that is a part of the sugar. The 5′ carbon is attached to a phosphate group. When nucleotides are joined together into a chain, the 5′ phosphate of one nucleotide is attached to the 3′ hydroxyl group of the next nucleotide, thereby forming a 5′-3′ phosphodiester bond. What this means is that when nucleotides are joined together in a chain, there will always be a free 3′ OH group (from the sugar) at one end of the chain and a free 5′ phosphate at the other end (Figure 3).

The two strands are anti-parallel in nature; that is, the 3′ end of one strand points in one direction, while the 5′ end of the other strand points in that direction (Figure 3). The sugar and phosphate of the nucleotides form the backbone of the structure, while the nitrogenous bases are stacked inside. Each base pair is separated from the other base pair by a distance of 0.34 nm (nanometer: 1 x 10-9 meters), and each turn of the helix measures 3.4 nm. Therefore, ten base pairs are present per turn of the helix. The diameter of the DNA double helix is 2 nm, and it is uniform throughout. Only the pairing between a purine and pyrimidine can explain the uniform diameter (3 “rings” across). The twisting of the two strands around each other results in the formation of uniformly spaced major and minor grooves (Figure 4). The major and minor grooves are very important for protein binding to DNA, but we will not be discussing this more specifically.

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. December 21, 2017 http://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.10:QhGQhr4x@6/Biological-Molecules