52 Elasticity of the Body

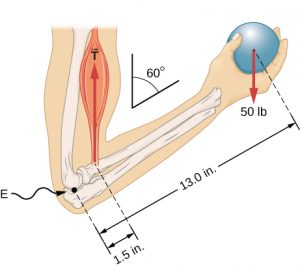

Biceps Tension

Earlier in this unit we found that 430 lbs of biceps tension are required to hold a 50 lb weight in the hand. Tension forces are restoring forces produced in response to materials being stretched. “The biceps muscle has two tendons that attach the muscle to the shoulder and one tendon that attaches at the elbow. The tendon at the elbow is called the distal biceps tendon. It attaches to a part of the radius bone called the radial tuberosity, a small bump on the bone near your elbow joint.”[1] In addition to the muscle, these tendons are under the same tension as the muscle, and are therefore being stretched. As long as the tendon is not stretched too far, it will behave elastically, meaning that it will return to its original length with no permanent deformation (damage).

Hooke’s Law

When objects, like the distal biceps tendon are only slightly stretched they will behave like springs. In that case the relationship between the tension force and stretch distance follows Hooke's Law and we often call the stretch distance the displacement, (![]() ):

):

(1) ![]()

If we wanted to use Hooke’s Law to calculate the stretch of the distal biceps tendon caused by the 430 lbs biceps tension for a particular person, we would need to know the spring constant of that person’s tendon. The spring constant depends on the stiffness of a particular material, known as the Elastic Modulus, but it also depends on the size and length of the object. For example, a wider tendon will not stretch as much as a narrow one, but a longer tendon would stretch farther than a shorter one. Modeling the tendon as a spring, we can think of stretching a tendon that has twice the cross-sectional area as equivalent to stretching a two of the original springs at the same time, which would require twice the applied force to create the same displacement. We can also think of a tendon with twice the length as equivalent to stretching two of the original springs placed end-to-end. To get the same stretch as a single spring, each spring will only have to stretch half of the total distance, so that would require only half the force to create the same total displacement. Therefore, the spring constant of the tendon (or any object) is proportional to the cross-sectional area (![]() ) and inversely proportional to it’s length (

) and inversely proportional to it’s length (![]() ).

).

(2) ![]()

Now we can see that the size of an object affects the spring constant. Therefore the force required to achieve a particular stretch is different for objects of different size, even when they are made of the same material. Replacing the spring constant in Hooke’s Law with the previous equation shows how force depends on cross-sectional area and length:

(3) ![]()

Everyday Examples: Biceps Tendon Stretch

We can use the previous equation to calculate the stretch in the biceps distal tendon for the 430 lb tension force required to hold a 50 lb ball in the hand. First we need to rearrange the equation for the stretch distance by diving both sides by ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

(4) ![]()

A elastic modulus for tendon is 1.5 x 109 N/m2.[3] [4]A typical length of the biceps distal tendon is 6.3 cm and a typical cross-sectional area is 1.5 x 10-5 m2 If we convert the length to meters (0.063 m) and the 430 lb force to Newtons (1913 N) we are ready to find the stretch distance using the previous equation:

(5) ![]()

The biceps distal tendon would stretch by an additional 2 mm when placed under the 430 lb tension.

Strain

Notice that the stretch in the biceps tendon that we calculated was dependent on the original length of the tendon. This makes sense because we know it’s easier to stretch a long object than a short one. For example, if you tie a body-length section of 1 cm thick nylon rope to a pole and then pull as hard as you can the stretch will be barely noticeable. If you instead used a rope with 10x body length, you would easily notice the stretch even though both ropes were made of the same material. In order to study the properties of specific materials like tendons, independent of size, we can divide the stretch by the original length. This quantity is known as the strain (![]() ):

):

(6) ![]()

Reinforcement Exercises

We need to be careful with the term strain because it has a different meaning in medical terminology where a strain is an over-stretching or tearing of muscle or tendon, which connect muscle to bones. A sprain is an over-stretching or tearing of ligaments, which connect bones together in joints.[5]

Elastic Modulus

Within the linear region we can model materials as springs, just like we did with the biceps distal tendon in the previous chapter. We can start by writing Hooke’s Law in terms of the material elastic modulus just as we did for the bicep:

(7) ![]()

Notice that the right hand side contains our definition of strain, so we can write

![]()

If we divide both sides by cross sectional area, we will suddenly have the definition of stress on the left:

![]()

So we can write:

(8) ![]()

We now see that when a material is behaving like a spring, the stress will be proportional to the strain and the elastic modulus of the material will be the proportionality constant that relates the stress and strain. When an object is behaving this way, we say the stress and strain fall within the linear region of the material. To actually find the elastic modulus of a material experimentally we rearrange the equation:

(9) ![]()

Then we just need to measure how much additional strain is caused by an applied stress (or vice versa) then divide the stress by strain to get the elastic modulus. Of course we need to be sure that the material is operating within it’s linear region, so that it still acts like a spring.

Reinforcement Exercises

Just as for the ultimate strength, some materials have a different elastic modulus when the stress is applied along different axes, or even between tension and compression along the same axis. For example, the tensile elastic modulus of bone is 16 GPa (16 x 109 Pa) compared to 9 GPa under compression.[6] Check out the engineering toolbox for a massive tensile elastic modulus table. For more information on stress and strain in human tissues, including excellent diagrams, check out posted lecture notes from Professor Tony Leyland at Simon Fraser University.

- "Biceps Tendon Tear at the Elbow" by OrthoInfo, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons ↵

- OpenStax University Physics, University Physics Volume 1. OpenStax CNX. Jul 11, 2018 http://cnx.org/contents/d50f6e32-0fda-46ef-a362-9bd36ca7c97d@10.18. ↵

- "Influence of biceps brachii tendon mechanical properties on elbow flexor force steadiness in young and old males" by R. R. Smart, S. Baudry, A. Fedorov, S. L. Kuzyk and J. M. Jakobi, Wiley Online Library ↵

- "The distal biceps tendon: footprint and relevant clinical anatomy" by Athwal GS, Steinmann SP, Rispoli DM., U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health ↵

- "Sprains and Strains" by Patient care and health information, Mayo Clinic ↵

- OpenStax, College Physics. OpenStax CNX. Aug 6, 2018 http://cnx.org/contents/031da8d3-b525-429c-80cf-6c8ed997733a@13.1. ↵

the force that is provided by an object in response to being pulled tight by forces acting from opposite ends, typically in reference to a rope, cable or wire

a force that tends to move a system back toward the equilibrium position

the restoring force exerted by a spring is equal to the displacement multiplied by spring constant

change in position, typically in reference to a change away from an equilibrium position or a change occurring over a specified time interval

measure of the stiffness of a spring, defined as the slope of the force vs. displacement curve for a spring

measures of resistance to being deformed elastically under applied stress, defined as the slope of the stress vs. strain curve in the elastic region

The cross-sectional area is the area of a two-dimensional shape that is obtained when a three-dimensional object - such as a cylinder - is sliced perpendicular to some specified axis at a point. For example, the cross-section of a cylinder - when sliced parallel to its base - is a circle

having a constant ratio to another quantity

the measure of the relative deformation of the material

region of the stress vs. strain curve for which stress is proportional to strain and the material follows Hooke's Law

a physical quantity that expresses the internal forces that neighboring particles of material exert on each other

the maximum stress a material can withstand

reduction in size caused by application of compressive forces (opposing forces applied inward to the object).