85 Weightlessness*

Uniform Circular Motion

We have seen that if the net force is found to be perpendicular to an object’s motion then it can’t do any work on the object. Therefore, the net force will only change the object’s direction of motion, change it’s kinetic energy) and the object must maintain a constant speed. The object will undergo uniform circular motion, in which case we sometimes refer to the net force that points toward the center of the circular motion as the centripetal force, but this is just a naming convention. The centripetal force is not a new kind of force, rather the centripetal force is provided by one of the forces we already know about, or a combination of them. For example, the centripetal force that keeps a satellite in orbit is just gravity and for a ball swinging on a string tension in the string provides the centripetal force.

For both the ball and the satellite the net force points at 90° to the object’s motion so it can do no work, thus it cannot change the kinetic energy of the object, which means it cannot change the speed of the object. How do we mesh this with Newton's Second Law, which says that objects with a net force must experience acceleration? We just have to remember that acceleration is change velocity per time and velocity includes speed and direction. Therfore, the constantly changing direction of uniform circular motion constitutes a constantly changing velocity, and thus a constant acceleration, so all is good. Due to Newton's Second Law, we know that the acceleration points toward the center of the circular motion because that is where the net force points. As a result, that acceleration is called the centripetal acceleration. If the net force drops to zero (string breaks) the acceleration must become zero and the ball will continue off at the same speed in whatever direction it was going when the net force became zero (diagram on right above).

Centripetal Force and Acceleration

The size of the acceleration experienced by an object undergoing uniform circular motion with radius ![]() at speed

at speed ![]() is:

is:

(1) ![]()

Combined with Newton's Second Law we can find the size of the centripetal force, which again is just the net force during uniform circular motion:

(2) ![]()

Everyday Example: Rounding a Curve

What is the maximum speed that a car can have while rounding a curve with radius of 75 m without skidding? Assume the friction coefficient between tire rubber and the asphalt road is 0.7

First, we recognize that as the car rounds the curve at constant speed the net force must point toward the center of the curve and have the value:

![]()

Next we recognize that the only force available to act on the car in the horizontal direction (toward the center of the curve) is friction, so the net force in the horizontal direction must be just the frictional force:

![]()

We want to know the maximum speed to take the curve without slipping, so we need to use the maximum static frictional force that can be applied before slipping:

![]()

Notice that we have used static friction even though the car is moving because we are solving the case when the tires are still rolling and not yet sliding. Kinetic friction would be used if the tires were sliding.

For a typical car on flat ground the normal force will be equal to the weight of the car:

![]()

Then we cancel the mass from both sides of the equation and solve for speed:

![]()

Inserting our values for friction coefficient, g, and radius:

![]()

Weightlessness

When you stand on a scale and you are not in equilibrium, then the normal force may not be equal to your weight and the weight measurement provided by the scale will be incorrect. For example, if you stand on a scale in an elevator as it begins to move upward, the scale will read a weight that is too large. As the elevator starts up, your motion changes from still to moving upward, so you must have an upward acceleration and you must not be in equilibrium. The normal force from the scale must be larger than your weight, so the scale will read a value larger than your weight.

In similar fashion, if you stand on a scale in an elevator as it begins to move downward the scale will read a weight that is too small. As the elevator starts down, your motion changes from still to moving downward, so you must not be in equilibrium, rather you have a downward acceleration. The normal force from the scale must be less than your weight.

Taking the elevator example to the extreme, if you try to stand on a scale while you are in free fall, the scale will be falling with the same acceleration as you. The scale will not be providing a normal force to hold you up, so it will read your weight as zero. We might say you are weightless. However, your weight is certainly not zero because weight is just another name for the force of gravity, which is definitely acting on you while you free fall. Maybe normal-force-less would be a more accurate, but also less convenient term than weightless.

We often refer to astronauts in orbit as weightless, however we know the force of gravity must be acting on them in order to cause the centripetal acceleration required for them to move in a circular orbit. Therefore, they are not actually weightless. The astronauts feel weightless because they are in free fall along with everything else around them. A scale in the shuttle would not read their weight because it would not need to supply a normal force to cancel their weight because both the scale and the astronaut are in free fall toward Earth. The only reason they don’t actually fall to the ground is that they are also moving so fast perpendicular to their downward acceleration that by the time they would have hit the ground, they have moved sufficiently far to the side that they end up falling around the Earth instead of into it.

Everyday Example: Orbital Velocity

How fast does an object need to be moving in order to free fall around the Earth (remain in orbit)? We can answer that question by setting the centripetal force equal to the gravitational force, given by Newton’s Universal Law of Gravitation (![]() = mg is only valid for object near Earth’s surface, remember):

= mg is only valid for object near Earth’s surface, remember):

![]()

Recognizing that gravity is the centripetal force in this case, and that ![]() is the Earth’s mass and

is the Earth’s mass and ![]() is the orbiting object’s mass:

is the orbiting object’s mass:

![]()

![]()

Cancelling ![]() and one factor of

and one factor of ![]() from both sides and solving for speed:

from both sides and solving for speed:

![]()

We see that the necessary orbit speed depends on the radius of the orbit. Let’s say we want a low-Earth orbit at an altitude of 2000 km, or ![]() . The radius of the orbit is that altitude plus the Earth’s radius of

. The radius of the orbit is that altitude plus the Earth’s radius of ![]() to get

to get ![]() or

or ![]() . Inserting that total radius and the gravitational constant,

. Inserting that total radius and the gravitational constant, ![]() , and the Earth’s mass:

, and the Earth’s mass: ![]() :

:

![]()

That’s fast.

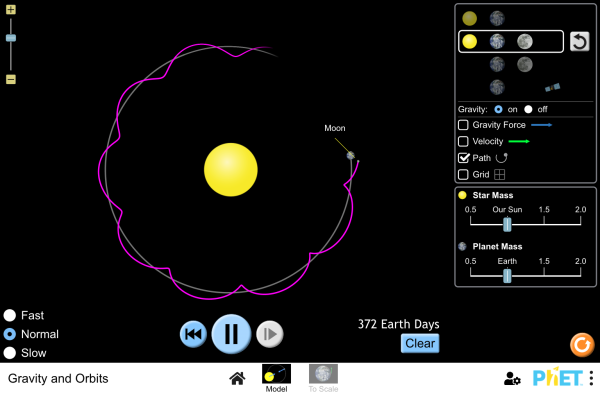

Use this simulation to play with the velocities of these planets in order to create stable orbits around the sun.

- Breaking String by Brews ohare [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons ↵

- Rob Oo from NL [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons ↵

the total amount of remaining unbalanced force on an object

A quantity representing the effect of applying a force to an object or system while it moves some distance.

energy which a body possesses by virtue of being in motion, energy stored by an object in motion

not changing, having the same value within a specified interval of time, space, or other physical variable

distance traveled per unit time

motion of an object traveling at a constant speed on a circular path

a name given to the component of the net force acting perpendicular to an objects motion and causing to take a circular path

the force that is provided by an object in response to being pulled tight by forces acting from opposite ends, typically in reference to a rope, cable or wire

the acceleration experienced by an object is equal to the net force on the object divided my the object's mass

the change in velocity per unit time, the slope of a velocity vs. time graph

a quantity of speed with a defined direction, the change in speed per unit time, the slope of the position vs. time graph

component of the acceleration directed toward the center of a circular motion

coefficient describing the combined roughness of two surfaces and serving as the proportionality constant between friction force and normal force

a force that acts on surfaces in opposition to sliding motion between the surfaces

a force that resists the tenancy of surfaces to slide across one another due to a force(s) being applied to one or both of the surfaces

the outward force supplied by an object in response to being compressed from opposite directions, typically in reference to solid objects.

the force of gravity on on object, typically in reference to the force of gravity caused by Earth or another celestial body

a measurement of the amount of matter in an object made by determining its resistance to changes in motion (inertial mass) or the force of gravity applied to it by another known mass from a known distance (gravitational mass). The gravitational mass and an inertial mass appear equal.

a state of having no unbalanced forces or torques

the motion experienced by an object when gravity is the only force acting on the object.

attraction between two objects due to their mass as described by Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation

at an angle of 90° to a given line, plane, or surface

every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force which is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers