64 Accelerating the Body

Newton’s Second Law of Motion

Newton's First Law tells us that we need a net force in order to create an acceleration. As you might expect, a larger net force will cause a larger acceleration, and the same net force will give a smaller mass a greater acceleration. Newton's Second Law summarizes all of that into a single equation relating the net force, mass, and acceleration:

(1) ![]()

Finding Acceleration from Net Force

If we know the net force and want to find the acceleration, we can solve Newton's Second Law for the acceleration:

(2) ![]()

Now we see that larger net forces create larger accelerations and larger masses reduce the size of the acceleration. In fact, an object’s mass is a direct measure of an objects resistance to changing its motion, or its inertia.

Reinforcement Exercises

Finding Net Force from Acceleration

Everyday Example: Parachute Opening

In the previous chapter we found that if opening a parachute slows a skydiver from 54 m/s to 2.7 m/s in just 2.0 s of time then they experienced an average upward acceleration of 26 m/s/s . If the mass of our example skydiver is 85 kg, what is the average net force on the person?

We start with Newton’s Second Law of Motion

![]()

Enter in our values:

![]()

The person experiences an average net force of 2200 N upward during chute opening. When the chute begins to open the body position changes to feet first, which significantly reduces air resistance, so air resistance is no longer balancing the body weight. Therefore, the harness needs to support body weight plus provide the additional unbalanced 2200 N upward force on the person. The skydiver’s body weight is Fg = 85 kg x 9.8 m/s/s = 833 N, so the force on them from the harness must be 2833 N. That force is actually more than three times greater than their body weight, but is distributed over the wide straps that make up the leg loops and waist loop of the harness, which helps to prevent injury.

Reinforcement Exercises

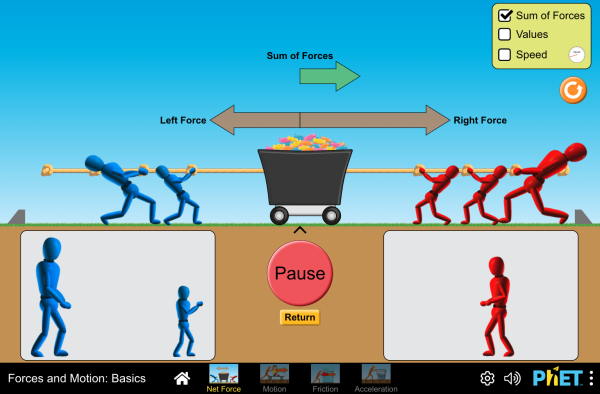

Check out this simulation to see how forces combine to create net forces and accelerations:

Free-Fall Acceleration

In the absence of air resistance, heavy objects do not fall faster than lighter ones and all objects will fall with the same acceleration. Need experimental evidence? Check out this video:

It’s an interesting quirk of our universe that the same property of an object, specifically its mass, determines both the force of gravity on it and its resistance to accelerations, or inertia. Said another way, the inertial mass and the gravitational mass are equivalent. That is why we the free-fall acceleration for all objects has a magnitude of 9.8 m/s/s, as we will show in the following example.

Everyday Example: Free-Falling

Let’s calculate the initial acceleration of our example skydiver the moment they jump. At this moment they have the force of gravity pulling them down, but they have not yet gained any speed, so the air resistance (drag force) is zero. The net force is then just gravity, because it is the only force, so they are in free-fall for this moment. Starting with Newton's Second Law:

(3) ![]()

Gravity is the net force in this case because it is the only force, so we just use the formula for calculating force of gravity near the surface of Earth, add a negative sign because down is our negative direction (![]() ), and enter that for the net force: :

), and enter that for the net force: :

(4) ![]()

We see that the mass cancels out,

(5) ![]()

We see that our acceleration is negative, which makes sense because the acceleration is downward. We also see that the size, or magnitude, of the acceleration is g = 9.8 m/s2. We have just shown that in the absence of air resistance, all objects falling near the surface of Earth will experience an acceleration equal in size to 9.8 m/s2, regardless of their mass and weight. Whether the free-fall acceleration is -9.8 m/s/s or +9.8 m/s/s depends on if you chose downward to be the negative or positive direction.

an object's motion will not change unless it experiences a net force

the total amount of remaining unbalanced force on an object

the change in velocity per unit time, the slope of a velocity vs. time graph

the acceleration experienced by an object is equal to the net force on the object divided my the object's mass

a measurement of the amount of matter in an object made by determining its resistance to changes in motion (inertial mass) or the force of gravity applied to it by another known mass from a known distance (gravitational mass). The gravitational mass and an inertial mass appear equal.

the tenancy of an object to resist changes in motion

attraction between two objects due to their mass as described by Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation

the size or extent of a vector quantity, regardless of direction

distance traveled per unit time

a force acting opposite to the relative motion of any object moving with respect to a surrounding fluid

a force applied by a fluid to any object moving with respect to the fluid, which acts opposite to the relative motion of the object relative to the fluid

the force of gravity on on object, typically in reference to the force of gravity caused by Earth or another celestial body